Deal Boost for Biocon

The firm is looking at partnerships with global pharma majors as a ticket to hasten the launch of its biotech products

When Indian biotechnology firm Biocon and the world’s biggest pharma company Pfizer announced their $350-million alliance in late October, the industry took it as another biotech-pharma deal — by now an industry staple — that added to the blurring lines between the two sectors. The deal, however, is much more than that.

For one, it’s an “equitable” sharing of risk and reward, says Biocon chairperson and managing director Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw. “Unlike other deals where small companies license their assets [drugs] and bigger companies make milestone payments, in this deal both parties will take ownership and share the risks.” Under the deal, Pfizer will market four of Biocon’s biosimilar insulin products in a global market estimated to be worth $17 billion by 2013. By 2030, the number of diabetics in the world is expected to touch 400 million, with one of every five in India.

The deal is a turning point for the 32-year-old firm poised to commercialise its novel drug programmes.

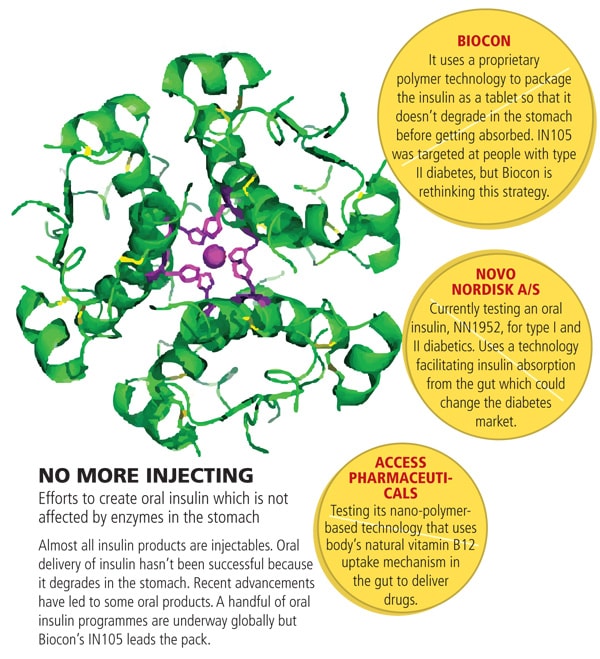

The first shot will be given to its flagship product, oral insulin IN105, which was initially slated for a mid-2011 launch in India. IN105 is not part of the deal with Pfizer and Biocon is looking for a global licensing partner, preferably a company that has a diabetes portfolio or the financial muscle and business to enter this segment.

“If we do a bigger trial on insulin-ready patients and prove its efficacy, we can unlock the real value of this product,” says Mazumdar-Shaw, who thinks launching IN105 in India would lower its partner’s commercialisation potential.

“It’s surprising that Biocon is doing this to its crown jewel,” says Vijay Chandru, chairman of Strand Life Sciences and president of the industry body Association of Biotech Led Enterprises. “Over the years I’ve seen that Kiran’s strategy is more about managing risks, rather than taking risks. It’s a sharp marketing strategy, though.”

For Biocon, this is a timely response to the evolving global scenario of disease management and drug commercialisation as policies and the standard of care change in different markets.

Partnership with Pfizer has given the company confidence to ask if it can pursue a similar strategy for other programmes as well, says Arun Chandavarkar, Biocon’s chief operating officer.

In 2011, Biocon will scout for a global licensing partner not only for IN105, but also for its two other frontrunners: Anti-CD6, a drug for psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis, and BVX-20, for treating a common cancer of lymphoid organs.

Since diabetes is a complex disorder with multiple treatment options, the right positioning of a drug is pivotal. While Biocon understands the science, it doesn’t understand the commercial reality in developed markets. “We don’t want to jump the gun by launching in India,” says Chandavarkar.

IN105 has been tested in India against metformin, a standard, cheap drug for type II diabetes. To launch IN105 as its substitute or as a second-line drug for people not responding to metformin or to other similar drugs, would be locking it in a particular position, believe Biocon officials. Moreover, IN105 is a new-age drug and would be more expensive than regular ones, making it tough for physicians to prescribe and patients to buy it.

Biocon has learnt from the industry, says Harish Iyer, head of research and development. He cites the example of Januvia, a drug for type II diabetes from Merck that is hailed for its marketing strategy. In 2007, it was introduced in the developed markets and then launched in India in 2008 at a price much lower than the market.

Although others see Mazumdar-Shaw as minimising risks, she calls herself “more realistic” and brushes aside any allusion that IN105 is a likely billion-dollar-drug from an Indian company. She says she no longer pins her hope on one product but depends on partnerships to fund novel programmes. “If I did not have this partnership model, I’d not have done justice to Biocon’s pipeline.”

It appears that India’s risk-averse biotech investor community may have fuelled this model, but this could be the way ahead.

In a November 29 report titled Biotech Reinvented, research firm PricewaterhouseCoopers says, working in a more collaborative environment requires organisations to “share assets and insight that they have previously ring-fenced for themselves, and this will require investors to take a longer term view on rates of return and change the funding model”.

The report estimates that collaboration can cut research and development costs of a product by $160 million and hasten its market launch by nearly five months. Usually, it takes more than $900 million and 10 years to develop and market a new drug.

In all these years, Biocon may have leveraged the local, low-cost base to test proof-of-concepts to build its pipeline. But, now, it certainly is looking global when the time for rewards is near.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)