Amagi's New Trick for Broadcast Advertising

Amagi wants TV advertising to become more targeted and much cheaper for advertisers. The channels aren't going to like it

Soon, while you are watching a show on national television, you might find yourself watching an advert for the mom-and-pop store down your road. In fact, even today while watching some channels, you might be watching advertising that is being aired only in your city. At the same time, your friend in another city who is watching the same show could be watching a different ad. The company behind this technology is the relatively unknown Bangalore-headquartered Amagi Media Labs. This four-year-old company is gradually disrupting the conventional wisdom and business model around TV advertising in India.

It has made a beginning with the UTV Group. Today, Amagi is one of the largest buyers of ads in the UTV Group’s channels. Amagi’s creative experts have churned out over 1,000 TV ads for small businesses across India in the last 18 months. Meanwhile, its 70-member sales force is busy selling TV ad slots to businesses across 35 cities in India, including Delhi and Mumbai, clocking up nearly $6 million in annualised revenue.

BREAKING AND MAKING

Amagi was founded in 2008 by three co-founders of Impulsesoft, a maker of Bluetooth software solutions for handheld devices, after its acquisition by US-based SiRF for $15 million. Venturing far from their previous domain, the three—Baskar S, Srinivasan KA and Srividhya S—decided to plant their new venture bang in the centre of India’s convoluted TV broadcasting industry. It has raised Rs. 37 crore in venture funding till date; all of it from Nadathur Investments and Ojas Ventures, both backed by Infosys co-founder NS Raghavan.

“TV was seen as a “reach” media, we wanted to segment it through targeting,” says Baskar, Amagi’s CEO. As new business ideas go, this one seemed suicidal.

Across the world, the TV broadcasting industry is complex and opaque with big and powerful intermediaries connected with each other through secretive and dense licensing and carriage agreements. In India it’s even worse, because the majority of the paid TV market is controlled at the customer end by hundreds of small-time cable operators.

But as Baskar saw it, the complexity was masking a massive inefficiency. In spite of hundreds of TV channels being present, advertising rates were still prohibitively expensive for small businesses because the ads were by default being shown to a national audience.

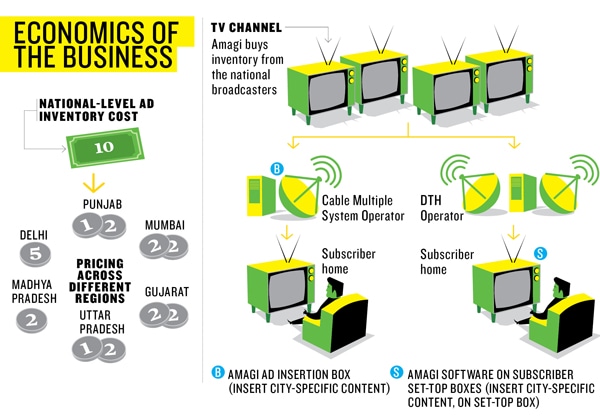

So, Amagi inserted itself into this ecosystem. It first built a software solution that would reside at cable operator “headends”—master facilities where numerous cable services and channels are aggregated before being transmitted to customer homes—and seamlessly insert a local ad into the national signal of a TV channel.

Because TV channels are notoriously risk-averse, Amagi assumed the risk by turning itself into a media buyer. It started buying pan-India ad slots from various TV channels before slicing and reselling them at much cheaper rates to local businesses in cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Patna and Mysore. Even larger brands can use this technology to display multiple locally relevant ads across the country at the same time, instead of being forced to run the same ad.

Amagi makes money by reselling an expensive national ad slot into tens of cheaper city-specific slots. “We want to buy an ad slot for Rs 100 and sell it for a total of Rs 200. We’re aiming for 50 percent gross margins. We’re not in this game for a small intermediary commission,” says Baskar. He says if an ad slot can be resold in even half of the cities where he currently operates, it is profitable.

Sameer Ganapathy, business head of UTV Movies and UTV Action says, “Unlike radio and print, retail advertising on television in the HSM [Hindi speaking markets] is yet to take shape and is an evolving process. Amagi is complementing our efforts to reach out to new clients.”

In cities where Amagi is unable to resell the ad slot, it either barters away to local radio channels or newspapers or inserts SMS-driven “daily deals” from e-commerce partners.

The beauty of the system is that the ad insertion in an individual city is done in an automated manner with no human intervention. And to incentivise cable operators, it shares with them part of the revenue it earns in each of the 35 cities it currently operates in.

But transparency and efficiency are not always welcome in the media industry. By allowing advertisers to choose a subset of a channel’s national viewership at lower rates, Amagi is directly attacking the business model of most TV channel groups, and the Amagi-founders are aware of the threat.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

“Take the IPL for instance. Why should a Vodafone which has 3G licences only in 9 circles, show an ad for 3G services all over the country? This threatens channels because it brings efficiency through unbundling,” says Baskar. UTV’s Ganapathy is cautious on the issue. “It is too early to comment till this model attains a critical mass. Also, Amagi provides technical solutions to enable this model to exist and can only implement this with broadcast partnerships. So the risks and gains are equally divided amongst all the stakeholders,” he says.

TAKING ON THE ESTABLISHMENT

That there is resistance on the part of TV channels to adopt Amagi’s technology can be seen from the fact that only 15 channels currently sell their ad inventory to it.

The biggest reason is that TV channels, like many other media, are sold in bundled “bouquets” that bunch together most of a publisher’s offerings for advertisers. This allows publishers to use their popular and established channels to cross-subsidise newer and niche ones.

Amagi’s offerings hit straight at that business model.

“Why would a Zee Group want advertisers to reach Bengali audiences through its other channels when it has Zee Bangla exactly for the same purpose?” asks Alok Mittal of Canaan Partners who has evaluated multiple companies in the new media space.

Bundling is a huge source of media profits around the world and every time a new entrant has tried to change that, the resistance has been immense.

“It’s also possible that broadcasters are afraid of losing some of the big advertiser spends that may move to use some of their own inventory, locally through Amagi,” says Ravi Kiran, a partner at advisory firm Friends of Ambition and the erstwhile CEO of media agency Starcom MediaVest for South Asia.

That conflict will only get more intense as Amagi shifts more of its focus towards large advertisers. “In the next three years we want to dramatically change our ratio of small versus large advertisers from 90:10 to 50:50,” says Baskar.

But to do that it will need to figure out a solution to the measurement problem.

Amagi relies on TAM (Television Audience Measurement), the dominant audience monitoring system, to provide advertisers with data about the local viewership of its channels. But TAM’s shortfalls—it extrapolates data from just 20,000 homes to arrive at viewership of nearly 150 million TV viewing households—get multiplied in Amagi’s local markets. Amagi will also end up competing with media buying agencies. Though, adds Kiran, “They can as well be a vendor to the agencies instead of a rival.” But there are more toes that Amagi treads on. The ad spends from local businesses which will move to TV advertising will come at the cost of local newspapers, radio stations, regional language and cable operator-run channels.

EXTENDING THE MODEL

With its primary business model largely in place, Amagi is now working on two significant extensions.

The first of these is going international. The issues faced by international channels like CNN, Disney and ESPN in South Asia and Latin America are similar to those faced by national channels within India. Because the same signal is broadcast all over these areas, the channels are forced to sell multiple countries to advertisers, naturally at very high prices. Even when large brands can afford those rates, there are other issues.

“Because liquor advertising is banned in Indonesia, the channels can’t run them in any other country too,” says Baskar.

By licensing its patent-pending technology to these channels, Amagi hopes to replicate its India business model internationally. It is currently doing trials with a few international channels and hopes to go live with them in six months.

Within India, it is co-innovating with DTH operators that are currently excluded from its targeting solution (because DTH signals are relayed directly from satellites to consumer homes, there are no headends to intercept and add local ads).

The first of these partnerships could be announced in another eight months. “We want to do TV ads like Google Adwords. A customer should be able to log in to a website, select Karnataka as a state, then Bangalore, then a channel and an ad slot, and finally upload their ad,” he says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)