Why India's Best CEOs Are Not Running Scared

Sure, the economy is down. But the best run companies have their eyes on the bright future

Mayank Pareek won’t forget the crisis of 2008 in a hurry. In November that year, less than two months after the infamous Lehman Brothers crash, India’s biggest passenger car maker, Maruti Suzuki, felt its blow straight in the jaw. By the end of that month, it suddenly lost a quarter of its sales compared to the previous year. December was no better. Sales fell by another 10 percent.

By then, analysts were already predicting the end of the world. What’s more, no one inside the company had witnessed a slowdown of this kind. What saved the day was that the senior team got on top of the situation with alacrity. “The slowdown forced us to do a lot of things differently that we hadn’t done earlier,” admits Pareek, executive director and one of the senior-most Indian executives at the Japanese multinational.

Almost on cue, Maruti’s sales made a smart comeback in January, posting a 5 percent rise. Its rivals though weren’t as lucky. Their struggle lasted for six whole months.

Four years later, Pareek and his team at Maruti once again face the same prospect of slowing sales. After the heady growth rates of 20-30 percent for the past two years, auto sales are likely to grow by just 5-10 percent in 2012. And that’s just the best case situation. If the economic turmoil in the Euro zone worsens—or the US unleashes a war on Iran, forcing oil prices to head north—there’s simply no guessing the wreckage.

Not to forget the year-long policy paralysis that has beset governance in India, held up investment and damaged investor sentiment. And so, if the UP elections throw up a hung assembly—and hurts the Congress’ chances of regaining its political legitimacy, governance could once again take a back seat. Forget about the General Sales Tax (GST) and hopes of a common market, or a Direct Tax Code that brings much-needed clarity on matters of tax. In fact, it could very well spark off the prospects of even a mid-term poll.

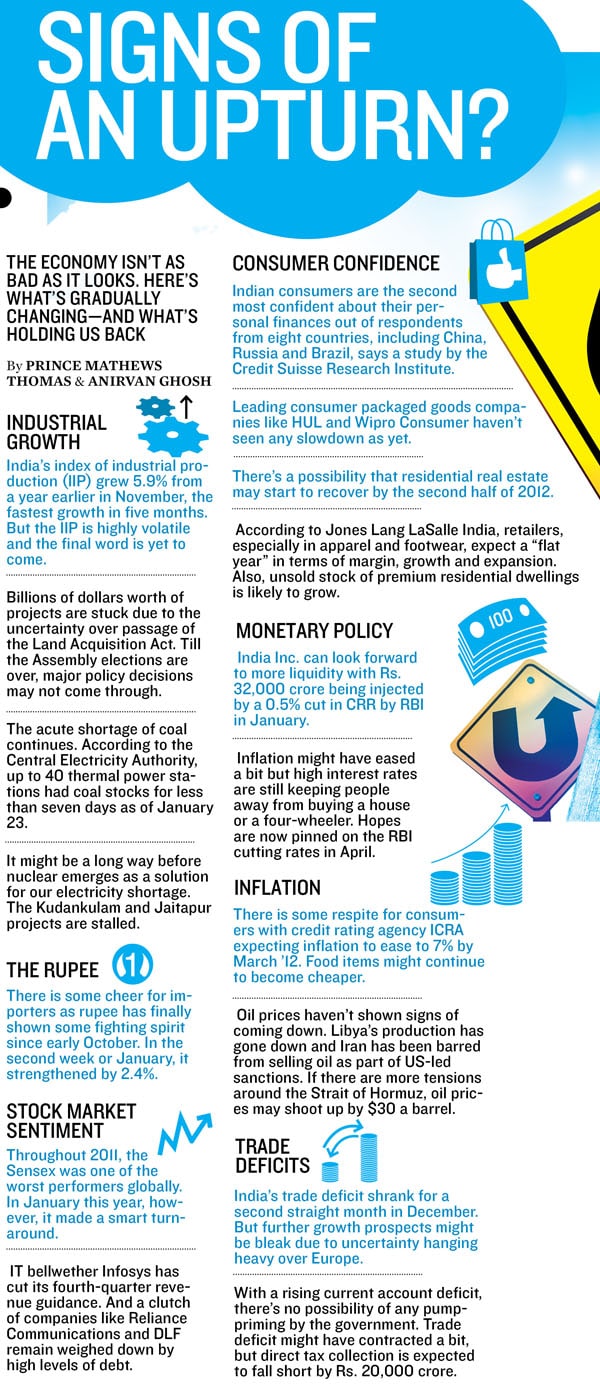

In 2008, the crisis came without warning. This time, things have been simmering for a while. Growth rates in India have come down, capital markets remain frozen for most part and money supply has been tight. Export demand across many categories has been hurt due to the massive slowdown in the West.

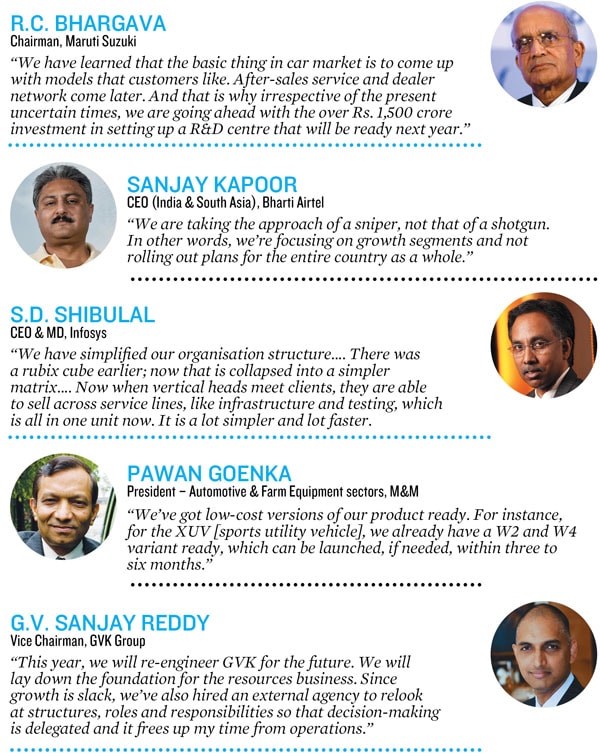

On the face of it, it seems like a whole big muddle. You’d imagine CEOs of even the best run Indian companies would be worried stiff—and tentative about how to plan, amidst all the uncertainty this year. But guess what? After talking to CEOs across industries as diverse as infrastructure, retail, software, financial services, telecom, and industrial products, it is amply clear that India Inc. is fighting back.

“In a situation of adversity, your grey cells start becoming more active. When you put steel into 1,500 degrees Celsius, its molecular structure starts to change. It is the same for our brains,” says Ajay Shriram, chairman and senior managing director, DCM Shriram Consolidated, a company which makes industrial intermediates.

As businesses hunker down to deal with the tough times, the next few months will prove whether they’ve indeed learnt the lessons from the 2008 slowdown. For the moment, let’s look at the range of interventions that they have up their sleeve.

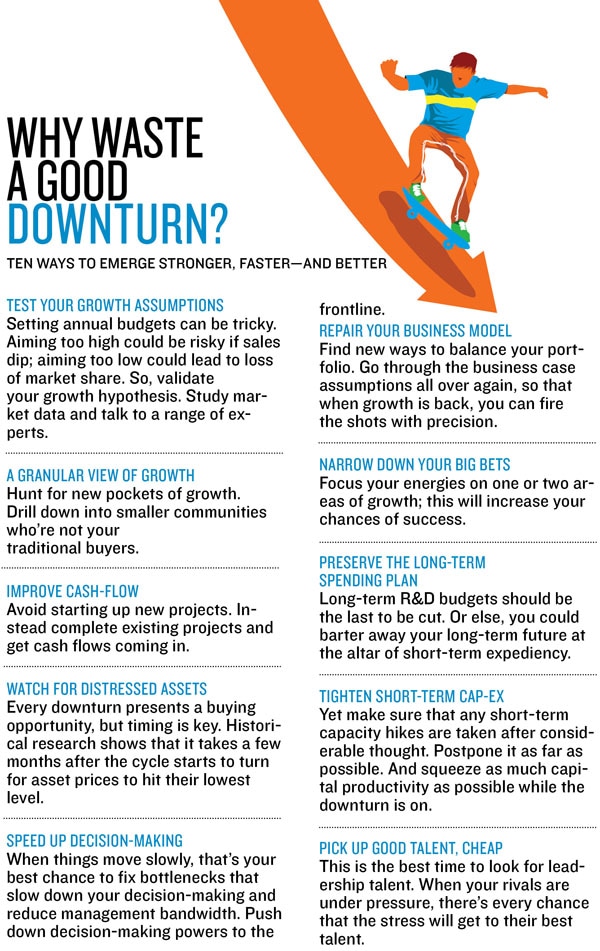

Stress-Test Your Growth Assumption

At this year’s Auto Expo in the capital, Pawan Goenka didn’t just spend time examining the shiny, new cars on display; he also spent considerable time chatting up his rivals on how they saw the year ahead. What the president of M&M’s automotive and farm equipment division heard merely confirmed what his own team had told him. Expect no more than 5-6 percent growth in the first half of the year and about 8-10 percent in the second half. That seemed to make sense, except that the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM), which M&M was part of, seemed to be a lot more bullish. It predicted a 12 percent growth in sales across the year in its report released at the Auto Expo.

That’s when Goenka took an unusual step. In normal course, M&M would have completed its budgeting exercise for the year by January. Goenka decided to take a rain-check. “We’ve pushed back our budgeting exercise by a few weeks to February,” he says. In the interim, his teams will re-validate their growth hypothesis all over again, so that their forecasts are a lot more robust. Part of that will mean carefully studying the SIAM report, which bases its projections on industry-wide data.

“Basing your decisions on data is very important, it removes subjectivity,” says S.D. Shibulal, CEO & MD, Infosys. Unlike M&M, Infosys perhaps has a relatively easier time doing its forecasts. “Our universe is our client base, and since 95 percent of our business is based on repeat orders, we have a good hold on client budgets and very often, we are part of the budgeting process,” he says. External issues like currency or country-specific regulations are then added as approximations to Infosys’s famed forecasting model. This data-driven approach, led by the uncertain European market, may have perhaps prompted Infosys to issue its fourth-quarter guidance, which predicted flat sales.

Forecasting methods may have become a wee bit more uncertain because of another factor: The level of competition. “Post 2008, the focus of MNCs on developing countries, especially India, has dramatically increased,” says Vineet Agrawal, president, Wipro Consumer Care and Lighting. MNCs are no longer happy with the 10 percent growth that they were used to. Targets are up by 20 percent for the next year. “You suddenly discover the Indian CEO no longer reports to someone in Hong Kong or Singapore. He now has a direct line with the worldwide CEO, who is now coming down twice to India,” says Agrawal.

Focus on Project Execution, Release Cash Flows

Batten down the hatches, stop bidding for new projects. Instead, focus on first completing the existing projects on time and releasing cash flows. At GVK Group, that’s exactly what Vice Chairman G.V. Sanjay Reddy is consciously doing. “In the past, growth was the biggest problem. How do we grow? We were desperate to get opportunities. The change now is that we are saying enough—forget about growth for now. Let’s figure how to get beyond from where we are,” says Reddy.

The basic rule that Reddy has laid down is: Protect the downside risk. In other words, figure out how not to lose. So for instance, GVK Group is pushing ahead with two hydel power projects of 880 MW that are under construction: One in Alaknanda and the other in Punjab. On its transport vertical, it has three more road projects under construction, which will be funded from the first project, which is already generating positive cash flows. And on its airports business, it is focussed on the Mumbai airport (which will be ready in a year from now) and Bangalore airport expansion.

While doing this, Reddy has pulled the plug on two gas-based power projects that were going nowhere because there was no fuel to get started. This is in spite of having sunk in over Rs. 200 crore in the ventures.

Arch rival GMR too is shifting focus from asset-building that defined its approach in the last decade to building cash-flows. Even till a year ago, GMR was among the most aggressive Indian companies bidding for practically every infrastructure project that was available. “We don’t want to go for new projects. We have to sweat these projects and get cash out of them,” says Subba Rao, president and group CFO, GMR Infrastructure. At the New Delhi airport, GMR is hoping to chivvy up cash flow, once the revised tariff order comes into effect from April 1 this year. There’s a plan to also monetise 1,500 acres of land at the Hyderabad airport. Both GMR and GVK are still weighed down by debt and their share prices have been beaten down on the bourses.

Protecting margins and sustaining cash flows isn’t an easy task in a commodity business, where raw material prices tend to fluctuate wildly. Ask Ajay and Vikram Shriram, the two brothers who lead DCM Shriram Consolidated, which makes PVC compound and resin for automotive, footwear and agricultural applications. It has tried to use every trick in its manufacturing book to cut costs and stay in the game. “Our ability to manage our raw materials, including changing them, is better because of the lessons learnt in 2008. We are more nimble now,” says Vikram Shriram. At their carbide plant, expensive carbon forms an integral part of the ready raw material for the furnace. The DCM Shriram group has developed a technique to substitute cheaper, undersized raw material and also used waste to reduce raw material costs. Similarly, for their power plant, the group has been able to use cheaper Indonesian coal, through process innovations done in-house, and saved on margins.

Hunt for New Pockets of Growth

When Maruti began to look at the root causes of the 2008 crisis, Pareek says they found much of the pain was isolated to the major cities, partly because of the meltdown in the Sensex. “While most of the major cities saw a drop in demand, cities like Dhanbad grew 47 percent. While that was from a lower base, the slowdown did not affect smaller towns,” he says. The same trend seems to be in vogue this year as well.

This is validated by Wipro’s Agrawal too. “Even in 2008, if you stepped out of the six-seven metros, life was running as usual. That’s because the lower middle class—a worker in the factory—did not lose his job. In my assessment, it was the stock market phenomenon, which only affects the large metros and cities.”

That’s why Maruti is making another determined bid to expand into the hinterland, just like it first did in 2008.

The way the auto maker has planned its expansion is interesting. It has tried to identify niches in every new market that it has entered. For example, blue potters in Jaipur and orange farmers in Maharashtra. “These are poor people, but two or three of them, who sit on top of the chain, make enough money to buy an entry-level Alto. There would be artisans in another town, five-six of whom make good money,” says Pareek. In all, Maruti has targeted 217 niches and claims that it sells nearly 5,000 vehicles a month to people in such groups. “The idea is to identify up to 300 niches this year, in order to make sure they can be served, and serviced properly.” This micro-marketing strategy is yielding results. Maruti has been able to penetrate deep inside rural India, with around 4 percent of its total sales coming from villages with less than 100 households. And around 26 percent of sales come from rural areas, up 3.5 percent in 2008.

True Value, its brand for second-hand cars, is also a vital strategy against the slowdown. It sold over 2,46,000 such vehicles last year, representing a 9 percent growth. And here’s the beauty: Many of these customers later make the transition to buying a new car from the company, when the economy recovers.

At the same time, it is making its marketing even more granular, thanks to its invaluable database of 9 million customers. “We took out past customer data and mined it. We could then better target those individuals who have been our customers before,” says Pareek. For example, one customer, presumably a fleet owner, in Lajpat Nagar, New Delhi, owned 30 Omni cars. After mining the data, the company found that the customer always bought the same model. He was then offered the Echo. He bought three of those.

Bharti Airtel is following much the same approach, targeting smaller segments of customers, rather than a pan-Indian one-size-fits-all strategy, which CEO Sanjay Kapoor describes as a sniper approach, as opposed to a shotgun approach.

Keep Your Eyes Fixed on the Long-Term

For one, M&M’s Goenka says he isn’t pulling back any of his long-term plans. In fact, R&D investments will always be the last to be cut, he says. “We have to invest today for growth three years from now. If we had slowed down our investments in 2008, we wouldn’t have the Reva acquisition and the XUV launch,” he says. Part of his plan is to be conservative about deploying capital in 2012-13, but continue investing for projects in 2016. For the short-term, he has one trick up his sleeve: As part of every new product launch, he’s keeping a couple of low-cost variants as a fall-back option. In case the market starts down-trading, he says he could launch two new variants of the XUV—W2 and W4—within three to six months.

Through this downturn, Infosys too is continuing to make long-term investments as part of its larger plan to be a global consulting and services company like an Accenture. Last quarter, it recruited 450 locals in various countries, and it upped that to 650 this quarter. Also on the anvil is a $120 million development centre in China, which will be ready in two years. “We want to increase our global talent. It fits in our strategic direction, which means we need more consultants and local managers. I don’t think I can transform a retailer in Germany without knowing German, we are staying our course,” says Shibulal.

While infrastructure was GVK’s forte in the last decade, in this one, Sanjay Reddy’s focus will be entirely on his big bet in Australia to emerge as a big resources company. It not only opens up an exciting new opportunity, but mining also helps de-risk the infra business model, where the lack of suitable coal linkages is crippling growth.

Over the next one year, Reddy says they will use the Hancock coal mines that they acquired in Australia for $1.5 billion last year to learn all about the resources business—and use it as a platform for growth over the next few years. “We are hoping to achieve financial closure of the project this year and start constructing,” says Reddy. Part of his confidence also stems from the fact that Reddy has been able to retain practically all of the 200 members of Hancock’s senior team.

Re-Look at the Current Business Model

There’s no better time to plan an organisational revamp, than when growth begins to slacken. Remove the chinks, speed up decision-making and even think about hiring better people, when the talent market isn’t overheated. That’s exactly what many smart firms are doing.

At Max Group, this is seen as the best time to go on a hiring spree. It put out ads in newspapers looking for agents for its insurance business. Last year, it let go of a whole bunch of non-performers and this year, it plans to up the quality of its sales agents. Part of that is driven by the changes in its business model, says Max India’s MD Rahul Khosla. After the IRDA regulations were changed, the whole industry has been moving away from ULIP-linked to more savings-related products. Still, almost 50 percent of the policies sold by life insurance companies are linked to equity investment. At Max though, almost 90 percent of the products sold are pure saving policies. This is useful in a slowdown because the returns in such policies are not as volatile as in the equity-linked ones, which track the stock markets.

Interestingly, selling these pure saving policies is tougher as the returns are lower than in an equity-linked one. But in a slowdown, customers are realising that at least their policies are not in the red and still give some returns. Thus, Max’s conversion rate—or the number of customers who continue to give premium in the second year—is the highest among private life insurers.

At JSW, there’s a big push to muscle into the territory vacated by secondary steel producers, who have been hit by high interest costs and costlier inputs. Secondary steel producers mostly make steel for the construction industry and many have cut production in the present slowdown. JSW is altering its product mix to make more and more of this steel and selling it through its retail stores, JSW Shoppe. This forms an important part of its overall strategy to de-risk its business model by reducing its export contribution and focussing more on the home market and other emerging markets like Africa and South East Asia, according to Seshagiri Rao, joint managing director and group CFO, JSW Steel.

At GVK too, an external firm is advising the promoters on how to relook at roles and responsibilities, speed up decision-making and improve the leadership talent pipeline. “This is a good time to hire leadership talent for our businesses as talent costs are somewhat more realistic,” says Reddy. A key part of the objective is to also free up the promoter’s time, so that he can focus more on strategy/growth. “When we looked at the gaps, we found that as promoters we needed to invest more time in meeting key stakeholders—and aligning the interests of key government officials and investors.” In a year’s time, once GVK starts to look for new opportunities in markets like Africa and Indonesia, it will allow Reddy to be at the forefront of that new drive to emerge faster, stronger and bigger.

(Additional reporting by Mitu Jayashankar)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)