Toyota's big small challenge

Even as Toyota looks to strengthen and redefine its presence in India by competing in the flourishing small car segment, it finds itself weighed down by unexpected battles

The announcement this March came as a complete surprise to many within Toyota in India. Toyota Motor Corporation (TMC) had announced that Akito Tachibana (54), who had spent just a few weeks in the country looking after the technical, purchase and quality assurance functions, would be elevated to managing director (MD) of the Indian operations, and the incumbent Naomi Ishi would return to Japan for a larger responsibility. Ishi had just completed two years as MD of Toyota Kirloskar Motor (TKM). This was the shortest stint for an India head; the average tenure for the job, in the past, has been close to four years.

This, however, wasn’t a comment on Ishi’s performance, which had proved effective: He had tamed shop-floor indiscipline at the company’s factory in Bidadi, on the outskirts of Bengaluru, revamped the quality of operations at the facility (the Indian arm today tops the shipping quality charts among Toyota operations worldwide) and returned TKM to profitability. Tachibana, a 30-year Toyota veteran, had been posted in Thailand as executive vice president, sales and marketing, earlier. His stint there was just a year.

The rationale behind the decision became clear soon. In end January, TMC announced its plan to raise its stake in the 109-year-old Daihatsu Motor Company, the oldest Japanese car-maker headquartered in Osaka and known for its affordable compact cars, from 51.2 percent—it had acquired the controlling stake in 1988—to 100 percent. Tachibana, an expert in product planning, had, over the past seven years, honed his skills in Vietnam and Thailand where compact cars occupy a significant proportion of the overall market. TMC, it became clear, was finally looking to launch a compact car by leveraging Daihatsu’s expertise and conquer its last frontier—India.

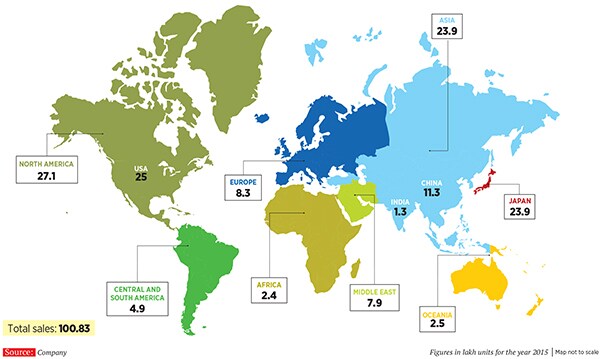

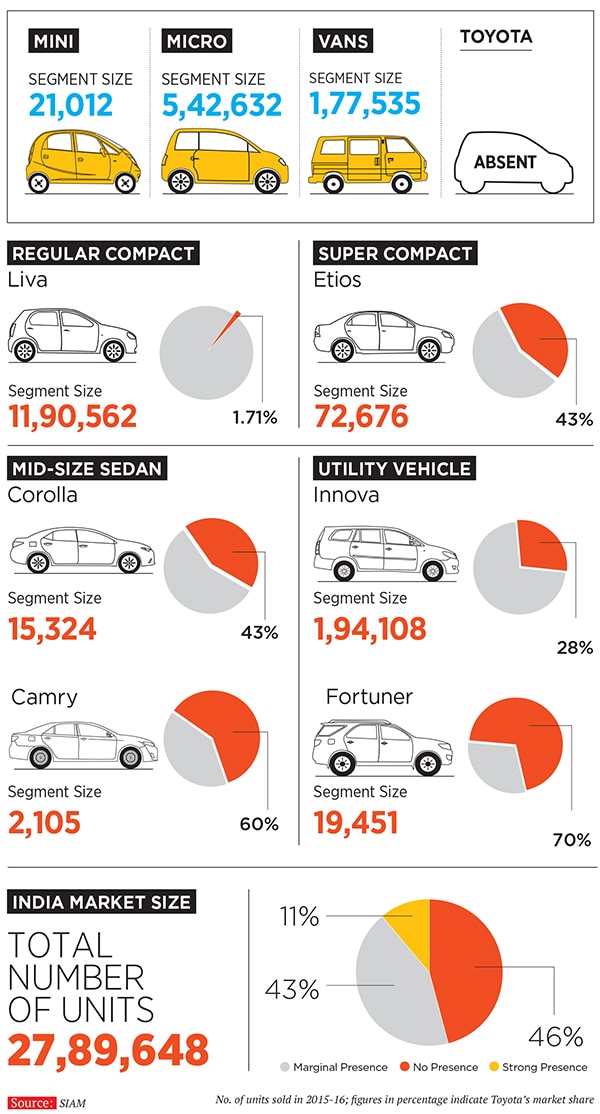

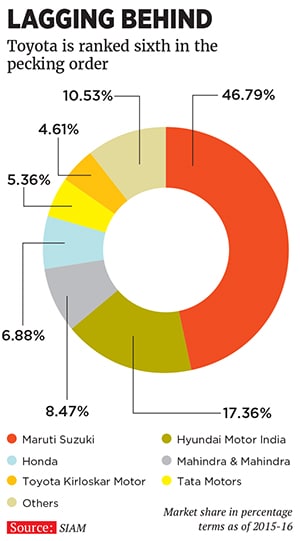

For TMC, the world’s 10th largest public company as per the Forbes Global 2000 ranking released earlier this year, India has been the most challenging market. TKM is a low sixth in the pecking order of Indian passenger vehicle manufacturers, with a market share of 4.61 percent (read Lagging Behind, p56). In comparison, compatriot Suzuki has 46.79 percent. TKM is either absent or has a marginal presence in product categories—such as entry-level cars, compact cars, vans or compact SUVs—that amount to 89 percent of the car market (read India Play, on p53). In the low-volume and high-value premium segments in which it is present, it does dominate the market: Its market share in the Innova segment is 28 percent, Corolla 43 percent, Camry 60 percent and Fortuner 70 percent. However, its overall volume in 2015-16 at 1.28 lakh units is almost half that of the 2.40 lakh units that TMC sold in Africa in 2015; TMC’s global sales in 2015 stood at 100.83 lakh cars.

In that context, it is easy to see why TMC has decided to shift gears in India. It has set a 10 percent market share as its target by 2025. This, the company knows, will be impossible without a small car in its product portfolio. “In a market like India, there is still [a] need for small cars. As soon as possible I would like to introduce that small car,” Kyoichi Tanada, Toyota’s CEO for Asia, the Middle East and North Africa told international wire agency Reuters at the Auto Expo in Delhi this February. “To fight in the small car market we need more support from Daihatsu… Toyota, by ourselves, cannot develop it.”

Tachibana was moved to India to get this strategy rolling, but six months into his term he is fighting an altogether different battle. “I knew India is the most challenging market in the world,” says Tachibana. “Customers here are very demanding and cost-conscious.” But what he did not bargain for is a policy environment that can alter abruptly and the changes are not always logical.

The De-dieselisation

On December 16 last year, the Supreme Court, while hearing a petition on air pollution in Delhi, passed a sudden order banning registration of all new cars and sports utility vehicles with diesel engines with a capacity of 2,000 cc or more in the National Capital Region (NCR). The order, initially applicable till March 31 this year, has since been extended till further notice. TKM, whose product portfolio predominantly comprises diesel engines with capacities of over 2,000 cc, was badly hit: It could not sell Innovas, Camrys and Fortuners in the NCR. “Overnight our dealers in the NCR lost 80 percent of their business,” says N Raja, senior vice president and director, marketing and sales.

Since the ban, the company’s overall Innova sales have fallen by 10 percent and that of Fortuner by 12 percent. This is especially since NCR also happens to be the largest market for passenger vehicles in India.

“We support efforts to reduce pollution, but the high level of pollution is not caused by cars alone. Punishing just the automotive sector is unfair,” says Shekar Viswanathan, vice chairman and whole-time director, TKM. “Even if you want to keep polluting cars off the road, banning sales of vehicles such as Innovas and Fortuners, which comply with Bharat Stage IV emission norms, is not the solution.” Vikram S Kirloskar, vice chairman, TKM, agrees. “Today the cars that are most polluting are plying on the roads, while sales of least polluting vehicles have been banned. This move will not clean up the capital’s air,” he says. “The better solution would have been to remove the older cars which cause maximum pollution.”

TKM’s attempts to explain to the court that a larger, more structured, plan is needed to tackle pollution have had little effect. “It is eight months now and the ban still continues,” says Raja. The National Green Tribunal (NGT) dropped another bombshell on July 19: It ordered regional transport offices in Delhi to de-register all diesel vehicles older than 10 years. “The signal such orders give is that diesel is an undesirable fuel,” says Raja. “Are petrol vehicles not contributing to pollution? This move will further drive people away from diesel models. There is already a 3 to 4 percent shift.”

The NGT order was the last straw for the company. “We have decided to put a brake on all product development and investment plans till clarity emerges,” says Viswanathan. “Policy flip-flops lead to uncertainty and it vitiates the planning process.” Other global majors such as Ford, General Motors and Fiat have also threatened to review their investment plans in India.

The policy flip-flops Viswanathan refers to is the manner in which the policy on diesel engines has swung from one extreme to another. When the UPA government restored control over prices of diesel, LPG and kerosene in 2004 (the NDA government had de-regulated both petrol and diesel prices in 2002), the gap between the cost of petrol and diesel widened. This saw a sudden shift to diesel engines, catching many automakers by surprise. They had then scrambled to build diesel engine manufacturing capacity. And now, diesel has suddenly become a bad word.

“We just set up a diesel engine facility at an investment of Rs 1,200 crore and its capacity utilisation is barely 30 percent today,” says Viswanathan. TKM appreciates the need to reduce pollution and wants to play a supporting role but “all we are saying is, allow us to do our business—don’t strangle us,” says Raja.

Despite the obvious angst, Toyota is hopeful. The Government of India has thrown its lot with the industry and has informed the apex court that banning new cars is not the solution. It has suggested, instead, a larger plan involving scrapping of old vehicles. “The judiciary [too] is beginning to understand us,” says Raja.

The Second Coming

TKM’s faith in the judiciary needs to be vindicated soon. “The buyout of 100 percent stake in Daihatsu by TMC will be completed in August. Top-level talks are scheduled after that for firming up Daihatsu’s entry into India,” says Raja.

Apart from identifying the right product and finalising its specifications, other factors also need to be resolved. For instance, how will the compact car be badged—as a Toyota product (the brand, ranked 6th in Forbes’s Most Valued Brands list this year, has a strong aspirational pull in India) or as a Daihatsu? Also, what would be the distribution strategy—will it be sold through existing dealers or will new dealers be appointed for the small car? Further, it also needs to decide if TKM’s unused capacity (the current capacity utilisation is 55 percent for car assembly and 30 percent for engine plant) would be utilised for manufacturing these cars.

“If the present uncertainty continues, Daihatsu, a much smaller company than TMC, will become cagey and hold back its India plans,” says Viswanathan. And if that happens, it will be the second time that Daihatsu’s entry into India would have been considered and then put off.

In 1996, when TMC first decided to get into India, it began talking to various potential partners, including the Hindujas, who own Ashok Leyland, India’s second-largest commercial vehicle player, and were looking at a foray into the car segment. During the talks, the Hindujas made it clear that to succeed TMC should launch a compact car by leveraging Daihatsu’s expertise.

But TMC demurred. It, like other global majors who entered India then, was reading the market wrong. It assumed that India, like China, will grow quickly to become a strong market for sedans and bigger cars. As a result, talks with the Hindujas fell through and TMC entered into a joint venture with Kirloskar Group, with whom it already had a business relationship. In 1995, Toyoda Automatic Loom Works (now Toyota Industries Corporation), one of the oldest companies in the Toyota group, and Kirloskar Group (which makes pumps and valves) had set up Kirloskar Toyota Textile Machinery near Bengaluru to manufacture textile machinery. On the back of that relationship, TKM was set up, with TMC owning a 74 percent stake then and Kirloskar the remaining 26. (It is now 89-11 in favour of Toyota.)

In 1999, they introduced Qualis, an SUV, followed by other models such as Innova, Corolla, Camry, Fortuner and Etios. “We thought Toyota’s product line and technology will get more suitable for the Indian market over time and we set up the plant to prepare for the future—build the dealer network, suppliers and the manufacturing capabilities,” says Vikram Kirloskar.

However, this shift by Indian consumers did not take place. Even today, almost 85 percent of cars sold are compact. Policy factors also thwarted a move towards bigger cars; for instance, the lower excise duty on sub-4 metre cars. “If you want to meaningfully participate in the India growth story, you cannot do it without a small car,” says Abdul Majeed, automotive partner, PwC India.

Ford, General Motors and even Honda realised this and corrected their strategy to launch India-specific small cars. TKM too made an attempt by launching Etios Liva in 2011 in the compact segment, but it failed to strike a chord with value-for-money customers. Etios Liva’s starting price in Delhi is around Rs 5.14 lakh while Ford Figo’s is Rs 4.40 lakh and Hyundai i10’s is Rs 4.30 lakh. Not surprisingly, Liva’s market share in that segment is just 1.7 percent. “Toyota is not good at making small cars,” concedes Tachibana. Hence, enter Daihatsu with its technology and processes to manufacture affordable compact cars.

TMC’s decision to enter the Indian compact car segment is also driven by certain regulatory factors. Phase I of CAFE (corporate average fuel efficiency) norms is due from 2017 and phase II by 2022. Having a strong mix of small cars in the portfolio is critical to achieve the mandated carbon dioxide emission target of 108 grams per kilometre by 2022.

Getting the basics right

Notwithstanding the challenges, some of which are out of their control, in the last couple of years TKM has worked hard to fix what it can: Quality.

To improve the standard of operations at its Bidadi plant, Naomi Ishi, the previous managing director, had cracked the whip: This led to a 40-day lockout in March 2014. “For high quality of manufacturing and productivity, discipline is needed. We enforced that and then changed the mindset of the employees to improve the way they do their job,” Ishi told Forbes India in January. Today, TKM’s shipping quality is among the best across TMC’s global production facilities.

These measures have improved the quality, reliability and operational efficiency of its products, which have led to a very low cost of ownership. “It is precisely for this reason that models such as Etios and Innova do so well for commercial operators,” says Tachibana. Subash Ghagre, a Mumbai cab driver operating for Uber, validates this assertion. He drives for 12 hours a day and has clocked 1.5 lakh km in his Etios. “Fuel efficiency is high and maintenance cost is very low. I have just changed oil and tyres so far. Low cost of ownership helps me to take home Rs 30,000 a month after all expenses [are paid],” he says. Etios sales in 2015-16 have risen by 17 percent over the previous year.

Regulatory changes in the offing will help TKM as they will level the playing field with its rivals in India. For instance, safety norms including the new crash test rules will come into force in 2017. But Toyota cars already satisfy these norms. “All our products are subjected to crash tests and they clear them,” says Tachibana. This obsession for safety can mean slightly higher prices for TKM products but the upside is that they have never failed crash tests conducted by independent laboratories—an ignominy other car makers in India suffer. “We have been pushing for crash tests and it is our competition which has been resisting it for so long,” adds Viswanathan.

Also, the Bharat Stage IV fuel emission norms are due to kick in shortly and carmakers are crying hoarse about the higher costs it will entail. “All our cars are already Bharat Stage IV compliant,” says Tachibana. Come 2020, Bharat Stage VI norms will be implemented and “we are ready for that too,” he says. “The gap between the cost of a Bharat Stage VI engine and a hybrid engine will narrow very sharply. Our hybrid cars will then become more attractive.”

Challenges Ahead

While these developments will come to TKM’s aid, they will not in any way diminish the challenges it has to overcome to make its compact car foray a success.

TKM has to master the art of frugal manufacturing, aggressive pricing and maintaining a high level of localisation. To achieve scale, a critical factor to reduce the cost of manufacturing, exports are important. Hyundai and Nissan have made India their global small car hub and benefited from it. TKM’s exports of 14,786 units from India in 2015-16 pales into insignificance when compared to Hyundai’s 1.62 lakh units and Nissan’s 1.12 lakh units.

The distribution network will also need a relook. “A strong small car player must have its distribution and service network in every nook and corner of the country,” says PwC’s Majeed. This would call for large-scale investment. Toyota currently has 294 dealers. Compare this with Maruti Suzuki’s 1,850 dealer outlets and 3,170 workshops and Hyundai’s 451 dealers and 1,172 service points.

Then, of course, is the question of product development capability. TKM’s record when it comes to new product launches is patchy. For one, the lead time is long. Crysta, its new variant of Innova launched in May, came after more than two years of no new products. The reason for this is that TKM is dependent on TMC’s R&D facilities, which are busy with the needs of bigger markets. “One criterion for succeeding with small cars is to launch variants aggressively to keep the product fresh. If you launch one car and then don’t do anything for years, it will not work,” says Majeed. To achieve this, TKM will either need greater help from its parent or will have to set up a dedicated product development facility for India just as Maruti Suzuki has belatedly done recently.

These are massive changes for TMC or, for that matter, for most Japanese companies who hold on to their tried and tested methods. RC Bhargava, Maruti Suzuki’s chairman who has spent decades working with the Japanese, understands their psyche well: “The Japanese are very conservative people. They find it extremely difficult to throw away what they have learnt over decades of experience. It is this attribute that sometimes makes it difficult for them to adjust in markets such as India which are different.”

But if Tachibana wants to achieve the vision of taking TKM to the next level, he needs to shed the typical Japanese reticence and adopt a bold new approach with the support of TMC. However, for now, his energies are being consumed by a more pressing matter—protecting TKM’s existing market share.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)