The Hindu: Board Room Becomes Battlefield

Fraternal fight erupts again in one of India’s oldest and most respected newspapers

As the two mighty armies lined up against each other at the Kurukshetra, and as the celestial conches, kettledrums and trumpets roared to signal the beginning of war, Arjuna was suddenly gripped by dilemma. “O Krishna,” he wailed. “It is my own cousins and uncles that stand as my enemies today. How can I derive any pleasure from attacking them? Isn’t this war a sin?” But the omniscient Lord who rode Arjuna’s chariot would have none of his pre-war jitters. He reminded him of his duty as a warrior and told him that a battle fought for a higher purpose was sinless.

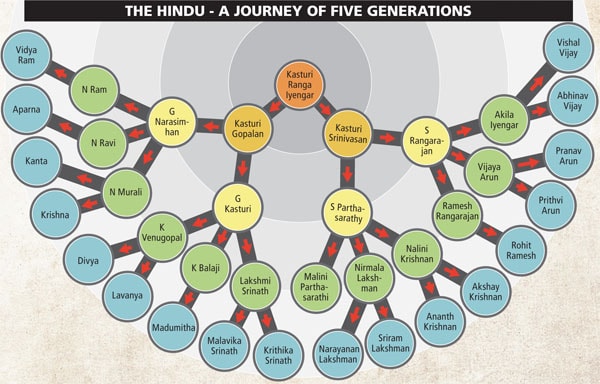

Chennai’s Anna Salai a.k.a Mount Road is no battleground and the most famous address on the road — headquarters of the 132-year-old English newspaper The Hindu — no monarchy. Yet, the second floor conference room of Kasturi Buildings presented an equally acrimonious spectacle on March 20. The board meeting represented by the four fourth-generation branches of the owners’ family started innocuously enough. On the agenda was a discussion on allocation of duties. But by the time the editor-in-chief and chairman, N. Ram, was done with his decisions, a full-blown reshuffle of the power structure has been effected. Some members of the family had been stripped of their responsibility, while others had gained fresh ground. Clearly, a battle of brothers for the overall control of the Rs.800 crore newspaper empire had begun.

At the receiving end on that day was Ram’s younger brother and managing director, N. Murali, who felt he had been “kicked upstairs” with a senior managing director designation while real powers had been shifted to cousins K. Balaji and Ramesh Rangarajan. Murali left the board meeting after four and a half hours of bitter argument and later heard that his elder brother had been quick to announce the changes through the company notice board. The news spread like wild fire among the 3,500 employees of The Hindu group and Murali had to react quickly. He wrote to them saying, “any communication purportedly removing my supervisory powers and departmental responsibilities is invalid and you may please ignore such communication.”

As the media got wind of the situation, statements and counter statements flew thick and fast, making it a very public dispute. But for its millions of readers, it was too much excitement that they couldn’t associate the paper with. “The Hindu always reminds me of an old maiden lady,” Jawaharlal Nehru had remarked once.

“...Very prim and proper, who is shocked if a naughty word is used in her presence. It is eminently the paper of the bourgeois, comfortably settled in life.”

But naughty words were indeed uttered in the course of the quarrel. Murali and N. Ravi, another director, accused their brother Ram of reneging on his promise to retire upon turning 65 this May and make way for younger members of the family. Malini Parthasarathy, 50, is waiting in the wings to edit the paper that she ran as executive editor in the 1990s. The fifth generation, in their teens and early 20s, are already beginning their careers in the paper and before long, would be vying for positions of responsibility.

In a rapidly changing business environment that demands fresh leadership, Ram should let go, say his brothers. Ram and several other directors did not respond to interview requests and questionnaires from Forbes India. At stake in this battle is the future of The Hindu. The younger generation has already expressed the need for improving corporate governance including norms for hiring family members and separating the ownership from management. Fresh competition in its strong markets — the South, especially Tamil Nadu — and a fall in advertisements have already started to tell on revenues. The group must prepare for tomorrow, by expanding on the Internet and attracting younger readers. It must also respond to increasing complains from long-time readers about editorial bias. And as a media house that has routinely subjected the establishment to scrutiny, it must answer questions its own shareholders raise about internal democracy and fairness.

THE MAN IN CHARGE: Backed by the board, N.Ram has further consolidated his position at the Hindu. Image: The New Indian Express

Chennai’s Super Kings

To begin a day in Chennai in an authentic fashion, you need all of three things: filter coffee, carnatic music and a crisp copy of The Hindu. The paper enjoys iconic status in the city. It has often been called the most respected newspaper in India. And the Chennai folk fondly call it Mount Road Maha Vishnu given its status as the protector of society’s values as well as its tendency to go into an Ananthasayanam (sleeping posture) on controversial issues.

But The Hindu had been a firebrand newspaper to start with. It was born in the anger of six friends — two teachers and four law students — who wanted to counter a campaign against the appointment of an Indian as a judge in 1878. They were called the “Triplicane Six” after the neighbourhood in Chennai they operated from. They championed a hard-hitting brand of journalism and a rudimentary form of Indian nationalism. But it was not until the paper passed into the hands of Kastur Ranga Iyengar, Ram’s great grandfather, in 1905, that it began to prosper financially.

Over the decades, The Hindu led the evolution of the country’s print media. It was the first to print in colour, use aircraft to deliver the paper, deploy computers, start facsimile editions and go on Internet. However, it focussed more on objective reporting than advocacy journalism. Its credibility rose so high that its readers began to say that they wouldn’t trust even a government gazette notification if not printed in The Hindu. Its critics said they could hardly see any difference between the two.

A particular low point was when the then editor G. Kasturi withdrew an editorial hours before publication on the day after the declaration of Emergency in 1975. The paper, against its own democratic instincts, supported forced family planning and the “discipline” that Emergency brought. It would take more than a decade for one of the family’s younger members — a US-educated, Left-leaning intellectual with a penchant for advocacy — to redeem the paper with a burst of anti-establishment, investigative stories.

Ram Rajya

With every generation change, The Hindu faced the inevitable change in attitudes. The fourth generation started coming into business in the 1970s and ‘80s and the eldest three among the 12 of that generation — Ram, Murali and Ravi — began to influence the paper. Ram and Ravi took the editorial route while Murali went into management. The two young journalists honed their skills in Washington before moving to bigger responsibilities at the head office.