Tata's Unending Quest For a Telecom Strategy

The iconic business group finds its search for a viable business model in mobile telephony business still elusive

On December 21, 2010, at 6:00 p.m., Ratan Tata met the newly appointed telecom minister Kapil Sibal at Sanchar Bhavan in the capital. The meeting — which came after several weeks of media accusing his publicist of trying to manipulate the previous telecom minister A. Raja — lasted for half an hour. In this meeting, Tata is said to have emphasised his most vocal demand to set right anomalies in the government’s telecom regulation and give his group a fair chance of doing business.

Ever since the taped conversations of Niira Radia were made public, Ratan Tata has been unusually vocal about his telecom business. In November last year, Tata publicly stated that a few telecom companies were hoarding scarce and expensive spectrum. That prompted Sunil Mittal, the head of India’s largest mobile phone operator Airtel, and Marten Pieters, head of the second largest player Vodafone Essar, to rebut his charges immediately.

Around the same time, Tata crossed swords with Rajeev Chandrasekhar, member of Parliament and the former CEO of BPL Mobile (now Loop), refuting what he called untruths and distortion of facts. He was referring to a letter Chandrasekhar wrote to him.

Why is Ratan Tata so upset? He is angry that his telecom business is looking to be lost inside the regulatory maze. He shouldn’t blame it all on the regulation though. While regulation is at fault, it is also a fact that his underlying business model is broken and needs some serious repair.

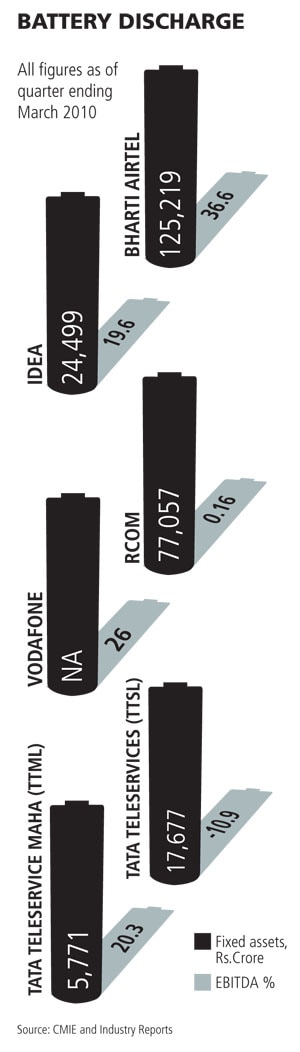

The business, today, is bleeding. The Tata group has so far invested more than Rs. 37,000 crore in the telecom business. Between its two companies, Tata Teleservices (TTSL) and the listed Tata Teleservices (Maharashtra) (TTML), the group has written off nearly Rs. 7,000 crore in losses, the biggest ever in recent times for the $80 billion group. Yet, last year (2009-10), it declared fresh losses of over Rs. 2,000 crore. Tata Communications, the third group telecom company which took over assets of government-owned VSNL, made losses last year after a large acquisition.

Having taken over the reins of the Tata group in 1991 from the iconic J.R.D. Tata, Ratan Tata is credited for several pathbreaking moves in the group, including the launch of Nano. The two flagship companies, Tata Steel and Tata Motors have grown several times under his leadership and have big international footprints.

The crucial question then is: Will Tata remain a significant, profitable player in the telecom space or will the investment go down as one of Ratan Tata’s worst ever business decisions? Kishor Chaukar, director, Tata Investments, who oversaw investments in the business, says, “Telecom is a core business for the group and we are in it for the long term.”

This or That

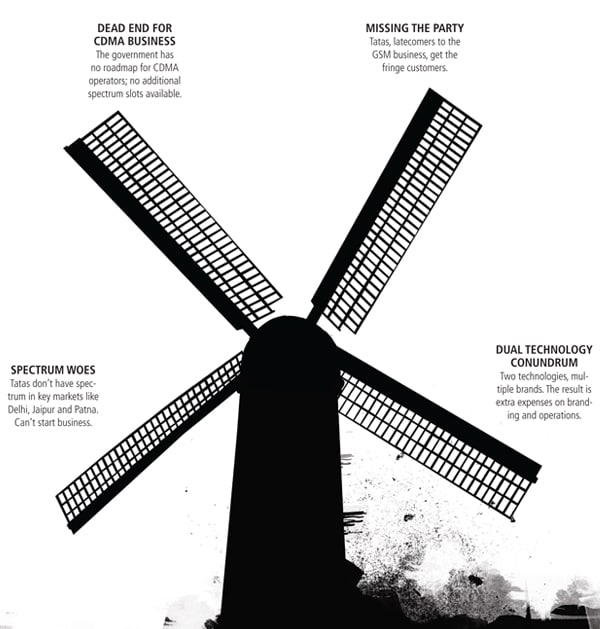

In planning for a core business, Tata’s thinking has not been easy to fathom. The group began by wanting to be a fixed line player. Later, it ventured into limited mobility wireless, then to full mobility wireless, and finally to dual technology. “Tatas have been half-hearted about this business. When Reliance went in for dual technology, they went the whole hog and took a pan-India license while the Tatas took only eight circles,” says an industry analyst. So how is Ratan Tata planning to revive the business?

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

The top management changes at Tata Teleservices offer some clues about the current thinking. Anil Sardana, the current CEO, credited with giving the telecom business some drive with his GSM push is going to head Tata Power, where he originally came from. N. Srinath, the current head of Tata Communications, will take over the reins from him.

Last year, a month before the launch of Tata DoCoMo’s GSM services, TTML’s managing director Mukund Govind Rajan moved to a new role in Tata Capital. Anil Sardana was given the additional charge of TTML, with a mandate to make support functions like HR and accounts shareable across the entities. But since Tata Docomo was being promoted as a brand distinct from Tata Indicom, it was necessary to set up a new customer facing organisation for the GSM business.

The Bombay House line is that Sardana is moving back to the power business as there was a legitimate vacancy after Tata Power’s managing director, Prasad Menon, stepped down. Sardana, too, says power is his first love. But Tata insiders read a different note on

the move.

A senior executive who has worked with Srinath says, “If Sardana can cut the flesh, Srinath can pare it to the bone.” Srinath’s express mandate is to take costs out and integrate the operations of all three companies: TTSL, TTML and Tata DoCoMo. Insiders reckon almost 2-3 percent of sales can be reduced. In itself that may not look like a big number but it can be a big thing for a company that’s running losses.

Srinath will have to make sure that revenue targets are achieved because the shareholder agreement contract allows DoCoMo to increase its stake in the event of this not happening. The key issue is that the competitive position of the business hasn’t improved even after the Tatas bid at the 3G auction. While experts and market studies indicate that 3G will be the next money spinner, the Tatas seemed to have quite a few pieces missing in their portfolio.

The group does not have licences for the high-end 3G services in Mumbai and Delhi. It stands to reason that these two metros will be early adopters of this new revenue source. The rollout of 3G services and falling prices of smart phones to less than $100 from $250 today, will be crucial drivers in the change. Mohit Rana, partner and vice president for telecom practice at A.T. Kearney, says, “The next big action in telecom will be in broadband and it will happen within a year’s time.”

Tata’s competitors like Sunil Mittal have seen the opportunity long coming. Despite having committed $10.7 billion to buy African telecom firm Zain, Mittal bid nearly $3 billion for 3G licences in thirteen circles and a further $700 million to buy broadband wireless technology licences, though eventually both the networks will duplicate bandwidth for data services.

Mukesh Ambani’s Infotel bought out a company with a pan-India broadband licence and is investing upwards of $3 billion to launch services by this year end. Vodafone also paid close to $3 billion to get 3G spectrum in nine out of the 22 circles. A senior Vodafone executive says, “It is the cost of staying at the top of the game for our customers.”

Not only does Tata not have Mumbai and Delhi, it also does not have any broadband wireless circles. The Tata group did not win any broadband wireless licences for any circle as the winning bid far exceeded the ‘walk away’ price. Chaukar says, “At that price, other options like enhancing our CDMA networks appeared more meaningful.” But given that the CDMA subscriber base is growing at just 2 percent, it won’t deliver the sort of revenues that will take the company to profitability.

The Silver Lining

To make money, the group has to make Tata DoCoMo, the GSM business, profitable. To be fair to the Tatas, this business has gathered steam and is now the main voice business company. In the last 18 months, after TTSL and DoCoMo jointly launched the services using GSM technology across the country, the venture has been ramping up subscribers faster than competitors.

The two Tata companies have more than 85 million subscribers, fourth in the pecking order. The two companies have reported further losses, which the companies claim are on account of the high initial capital expenditure to start the GSM business. Chaukar says, “We hope to break even faster than we did in the first round of investments in the CDMA business.”

That is, however, not the way others read the situation. A former CEO of a large mobile telephony company says that the Tatas are spending big money in recruiting low usage prepaid customers. As the churn rate among these customers is very high, Tata may not be able to even recover the cost of customer acquisition from the usage. Another CEO of a large GSM player, who did not wish to be named, says that Tata’s telecom business is a washout. “Over a long period of time, if you keep writing off loses, any business will be profitable,” he says.

A senior executive in Idea says that it is necessary to build the business in a few circles profitably before expanding to other circles. Idea came to Mumbai after successful launches in Madhya Pradesh. Airtel came to Delhi having a formidable set up in Delhi, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka.

Deepak Gulati, the man who heads Tata DoCoMo, does not agree. He argues that a late entrant has no such luxury but has to do ‘land grabbing’ quickly. So far, as mobile number portability (MNP) didn’t exist, companies like TTSL had to even look for customers who wanted a second mobile SIM. He says that as the fourth or fifth player, the focus is now on increasing the network usage while simultaneously trying to make more customers stick to the network. For example, its experiment with per-second or per-character-for-SMS billing, got it higher overall revenues even though it meant lower per customer revenues. Gulati says, “Our near term target is to be [among] the top three telecom companies in India.”

Frankly, Gulati can’t do any other thing. Telecom markets are getting saturated so quickly that he just has to grab subscribers as quickly as possible even if they aren’t very profitable. But ever since competitors matched its price cuts last year, the rate at which new customers are being won has come down. Now with the advent of number portability, grabbing subscribers will be a tougher task. Customers will normally switch to market leaders or if the network has exceptional voice clarity. Tata has neither the leadership nor the right type of network. It has the 1,800 MHz frequency band, which isn’t the best for voice clarity and competing on that front will be hard.

Worse, it has to pay other operators for carrying traffic for it in some very key markets.

For example, it will have to launch 3G services in Mumbai and for that it has to do a deal with another telecom company like state-owned Mahanagar Telephone Nigam (MTNL) to launch its services. The situation is similar to TTSL’s current predicament in Delhi. As it does not have GSM spectrum in the capital, it has to pay another operator a charge for allowing its customers to roam there.

The story is the same in 39 other circles where it does not have GSM spectrum. Similarly, in states like Karnataka, Tata Telecom has to climb two mountains — lack of spectrum and additional capital expenditure — to come on par with the biggest players.

TTSL has 4.4 MHz of spectrum in Karnataka in the 1800 MHz band as opposed to 10 Mhz of Bharti or 8 MHz of Vodafone. With no additional spectrum available, the only way forward will be to expand coverage by putting up more towers. For its CDMA business, Tata again has 3.75 MHz of spectrum, lower than the minimum 5 MHz required to offer quality services.

Since it started out late in the GSM business, it is a distant fourth or fifth player in every circle. A senior executive with Idea Cellular asks, “How can they be competitive if they have to incur additional costs at every stage compared to a profitable competition?”

Waiting for Policy

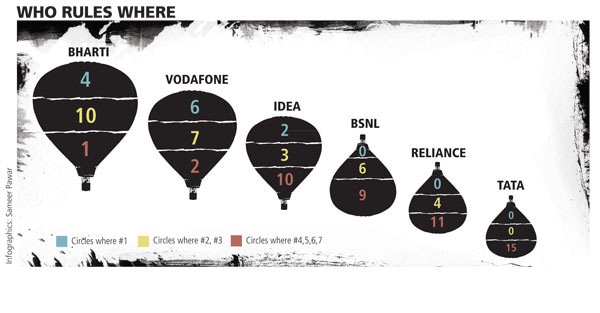

Tatas, who feel victimised, think that Kapil Sibal might be able to do something. With his 100-day promise for a new telecom policy and intent of regularising old policy anomalies, there is a belief that the industry will get a level playing field not only for all players but all telecom technologies like CDMA and GSM and eventually LTE (long term evolution). The ability to make money in Indian mobile telephony depends on the number of circles where an operator has leadership positions [number 1 or 2] On this count Bharti and Vodafone are well placed, with Idea in the third spot. Tata Teleservices is yet to dominate any single market. Also, Tata has got the 1800 Mhz frequency in all its markets and spends at least twice as much as Vodafone or Bharti on setting up its network

The ability to make money in Indian mobile telephony depends on the number of circles where an operator has leadership positions [number 1 or 2] On this count Bharti and Vodafone are well placed, with Idea in the third spot. Tata Teleservices is yet to dominate any single market. Also, Tata has got the 1800 Mhz frequency in all its markets and spends at least twice as much as Vodafone or Bharti on setting up its network

The speed of implementation of the mobile number portability is being touted as a proof of Sibal’s intent. In December, Tata wrote in his letter to Rajeev Chandrashekhar: “When the present sensational smokescreen dies down, as it will, and the true facts emerge, it will be for the people of India to determine who are the culprits that enjoy political patronage and protection and who actually subvert policy and who have dual standards.”

If Ratan Tata is waiting for the moment when ‘excess’ spectrum will be taken back from some of the existing players and then re-allocated to Tata Teleservices, he might have to wait a long time.

But the stakes are high for everyone in this game. Already rivals like Airtel and Vodafone are talking a different language. Even as Tata is charging others of enjoying excess spectrum, Martin Pieters, CEO of Vodafone, claims that Tata is hoarding spectrum. In an interaction with a daily financial paper, Pieter said that Vodafone paid Rs. 154 crore per MHz on an average for 144 MHz of spectrum, in comparison to TTSL which holds 157 MHz and paid just Rs. 37 crore. Reliance on the other hand paid just Rs. 48 crore for a total 206 MHz of spectrum. Simply put, it wont be an easy walk for the Tatas.

Regulatory change is not something Tata can factor in immediately. At the moment, though, Srinath can only try and see how quickly the Tata DoCoMo business can become profitable.

Deepak Gulati, who had come from Airtel, operates with his team out of Delhi while the Indicom and TTML operations were based in Mumbai. The two companies have different agencies to plan commercials. They also sell their products through separate channels and operate as different companies within the same organisation.

Finally, unlike Airtel and Reliance whose international long distance networks operations were part of their operations, the Tata companies have had to rely on Tata Communications to launch international products like calling cards. Since integrating all the different group companies are fraught with regulatory and ownership problems (two companies are listed and one is an unlisted joint venture with a foreign partner), the Tatas now expect to at least operationally synergise the three organisations. Gulati says, “However small operational costs we shave off in the current scenario, it is going to be useful.”

The Long Road to Profits

For starters, Gulati has started heading all the mobility business of the company and will be second only to Srinath. Similarly, the sales and network heads of the CDMA and GSM businesses have been merged at the top. Going forward, as the same telecom towers support both CDMA and GSM network equipment, the technical team will be slowly synergised.

On the sales side, now only one agency will handle the Indicom and DoCoMo brand. In the months ahead, more and more of the 3,000-odd Indicom sales outlets will start stocking DoCoMo wares. Sardana says, “Our initial strategy to absorb the costs of keeping DoCoMo separate has paid off in retaining our profitable CDMA customers.” But Sardana admits that profitability is still some way off. He says that since the group invested close to $3 billion in licence and network rollout expenditure for GSM only eighteen months ago, it will be sometime before the Tata Docomo side of the business will turn EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) positive.

Chaukar says that the business should be viewed in three silos based on the time when they committed the investment. The first licence business — the early CDMA licences and fixed line business bought out from Hughes in Maharashtra and the mobile business in Maharashtra — are already profitable. So, on a standalone basis, Tata’s entire CDMA business is profitable. Chaukar expects that second licence business — the GSM — to turn EBIDTA profitable quicker than the first.

He reasons that if one were to look at it as a new licence business, Tata has had to pump in lesser capital investment as the GSM equipment rode on the 24,000 towers already erected for the earlier network. Over the last eighteen months, the company has added some 15,000 more towers and sold a stake in the tower business to Quippo. Finally, as the current network is built 3G ready with DoCoMo’s help, the third licence business — 3G — is expected to make profits quicker than the first two. Romal Shetty, telecom specialist with consulting firm KPMG, says, “Docomo specialisation in value-added 3G services could prompt a change from incumbent operators.” But before that, Srinath will have to take some tough decisions to get strategic partners into circles where Tata Teleservices is very weak. In some states like Kerala and the North East Tata’s CDMA operations have fared badly with 800,000 and 76,000 subscribers respectively.

The company is said to be closely studying an option to hand over the subscribers, with their permission, to another operator if carrying on in a given circle does not make business sense. A senior executive says, “These are decisions that will require a lot of buying in within the organisation and an internal person like Srinath can hasten the process.”

Srinath may be an insider but some of these tasks are so tricky that even for someone of his experience, tying up all loose ends may just take too much time. And that’s a commodity that might run out for the Tatas even if their money doesn’t.

(Additional Reporting by Shishir Prasad & Rohin Dharmakumar)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)