SBI's First Lady A Harbinger of Change?

Arundhati Bhattacharya has taken charge of the country's largest bank during a critical phase. Will the 57-year-old veteran State Banker be able to push through her agenda for change against the odds?

It’s a regular working day at the State Bank of India’s imposing 19-storey headquarters in the south Mumbai business district of Nariman Point. A steady stream of visitors passes through the metal detectors at the gate and then on to the elevators for their meetings. Our stop is the 18th floor, where the top management of the country’s largest bank (standalone balance sheet size of around Rs 17 lakh crore) sits. It is business as usual, with senior executives going about their schedules. But beneath the veneer, change is brewing; change which, if allowed to run its course, could alter the way the country views its largest, and arguably most important, public sector bank.

Not least among the changes at SBI is the fact that the bank, which has its origins in the early 19th century and has morphed into a gigantic monolith, now has a woman in the corner office for the first time in its history. However, Arundhati Bhattacharya, 57, must still call herself ‘chairman’ because of a legality—the State Bank of India Act, 1955, does not recognise the position of chairperson. But this hangover of the past is hardly top of her mind. Instead, Bhattacharya, who meets us in between meetings, is a lady with a plan, someone who is acutely aware of the challenges that await her and the transformation she must effect.

“We have seen good leaders come and change the image of the bank, but after a while it slides back again. That’s because changes which are driven from the top take very long to stabilise, and none of the people at the top have that kind of time. So now I want to bring change from below,” she tells Forbes India, emphasising that any change must include the rank and file, the 2,22,000-plus employees who comprise the State Bank of India.

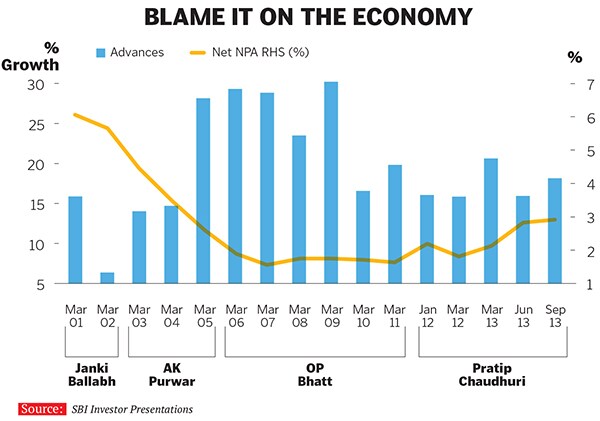

And change is now an imperative for SBI, as was evident just days after she took charge in October 2013. The second quarter results showed a 35 percent fall in net profits, its worst in two years, thanks to a steep jump in staff expenses and loan loss provisions, and the stressed assets situation looked rather ominous. Both gross non-performing assets (NPAs) and net NPAs saw a sequential rise of 8 basis points. However, there was some good news even as the asset quality remained a big worry: There was a sharp 39.23 percent drop in fresh NPA slippages, dipping in absolute terms from Rs 13,766 crore in the June 2013 quarter to Rs 8,365 crore in September.

The market quickly interpreted this to mean that the bank was getting a hang of the problem of asset quality and the stock rose the day after the results. But Bhattacharya, a veteran at SBI who joined the institution in 1977 as a probationary officer, knew only too well that this is hardly reason to celebrate. Huge challenges awaited and she had only just begun.

The 35 percent drop in profits that greeted Bhattacharya’s arrival at SBI was just one episode in a sequence of problems the bank—and many of SBI’s competitors in the public sector in particular—finds itself in. With the economy slowing down significantly and some key sectors such as infrastructure taking a serious hit, corporate bottom lines have been under severe pressure. This led to a Rs 9,306 crore increase in the bank’s restructured assets in the September 2013 quarter alone. If the December quarter results, which came in just as this issue was going to press, is any indication, the road ahead appears equally rocky.Net profit fell for the fourth straight quarter, down 34 percent, as bad loans took their toll. Net NPAs rose 33 basis points during the quarter.

One of Bhattacharya’s first statements after taking charge was about keeping NPAs under control—and that resolve continues. “Not only must we focus on recoveries, but there must also be a proper plan so that, going forward, the flow becomes more controllable,” she says. “There must be early warning signals and stronger post-sanction monitoring. A lot of care is taken pre-sanction, but post-sanction is important and that’s the less glamorous part of the business.”

Technology, Bhattacharya says, will play a major part in SBI’s NPA management plan by generating early warning signals. “We would like to use IT a lot more, since it can give us greater insight than what we’re using it for. I am trying to put together a good business analytics team which will give us that edge.”

The big worry for the bank on stressed assets is on the mid-corporate and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) side, sectors which typically bear the brunt most when an economic slowdown takes place. Mid-corporates contributed 38.6 percent of the total gross NPAs of the bank in December; the SME sector was next with 25.6 percent.

“Yes, the mid-corporate sector is stressed, and we’re taking it account by account,” says Bhattacharya. “Ours is a laborious strategy, but that’s the only strategy you can have. There’s no one solution which fits all, because different asset classes behave in different ways.” Large corporates are able to sell assets to bring in equity because they are diversified and present across geographies. But the more worrying segments are the mid-corporates and the SMEs which don’t have that ability.

Various internal committees at SBI are currently poring over different strata of accounts and analysing them so that data is easily available at any given point in time. “It’s a very deep study which is being undertaken,” says Bhattacharya.

As the country’s largest lender, SBI has played a role in nearly every major project flagged off over the past several decades in the country, and across sectors. While this has added heft to its balance sheet, it has also brought its share of problems. For instance, the infrastructure sector—currently reeling under the impact of the slowdown—accounts for 13.96 percent of the bank’s total domestic advances. Within infrastructure, around 42 percent is to the trouble-ridden power sector, while telecom and roads & ports account for about 14 percent each.

But Bhattacharya is not wringing her hands because of the bank’s exposure in these sectors. “Infrastructure and power are things required for the country. Had we not participated in the process of setting these up, would the 8.5 percent growth that we were so proud of have happened? Infrastructure is not something we have done for long. We, along with the rest of the country, have learnt from it,” she says, pointing out that the problem is essentially one of long-term assets being funded by short-term money. If a road asset takes 30 years to build and the plan is to fund it with 10-year money, it would need to be repaid in 10 years. “If you ask for repayment in this short term, you’re frontloading all the repayments. That can only work if the timing of execution and the growth assumptions are correct. But that does not happen.”

Bhattacharya says she talks to the bank’s corporate clients ‘on a daily basis’, adding that even they don’t want their reputations sullied and are making serious efforts to clean up their balance sheets. “They are conscious of the reputations they have built. We have seen them taking steps. We’ve seen GMR selling something, Jaypee selling something. But it’s not easy,” she says. “These things [sale of assets] take a lot of discussion, and even if you start diligence now, a minimum of six to eight months is required for them to fructify. Sale is like a marriage. It has to work. They don’t happen that easily. There are a number of serious discussions that are going on right now and we hope to see results.”

The banking industry, however, believes there needs to be an enterprise-wide risk management structure at SBI for it to be able to address the problem of mounting stressed assets. “There needs to be better loan underwriting skills, better loan on-boarding and post-disbursement monitoring,” says Romesh Sobti, managing director and CEO of the private sector IndusInd Bank and a former State Banker. He says the problem could also be on account of excessive delegation at the branch level. “Do those at the branch level have the requisite skills? Is there too much delegation at the branch level? If you compare this with the private sector, you will find there is hardly any delegation. And if there is delegation, there must be very strong oversight,” says Sobti.

A shortage of skilled employees is a challenge as big as that of managing NPAs. Having performed over 10 different roles—from retail and corporate banking to foreign exchange, treasury, new businesses and even human resources in her time at the bank—Bhattacharya has an understanding of the skills required for each and how poorly the bank is equipped in many cases.

“The main thing is to match various roles and people. Finding that equivalence is very difficult,” she says.

Unless she does something about it quickly, the skills shortage SBI faces has the potential to derail everything. Simply put, SBI’s workforce is ageing. Worse, there’s a big hole in the middle of the cadre as far as skilled workforce is concerned.

Earlier, about 250 people used to join SBI as officers every year; that number has now grown to 2,500. However, the bank still needs many more officers and is forced to promote from its clerical staff. “The clerical staff quality is good but we need more officers. In between, public sector banks had stopped recruiting for 12 long years. So the same lot of clerical staff was getting panned for bringing out another batch of officers. By the time the 12th lot came out the quality had deteriorated,” says Bhattacharya. “The workforce is also ageing. So now even after getting promoted, they are retiring by the time they reach scale II or scale III. So there is nobody to take up the scale IV and V.”

Adds Ranjit Goswami, SBI’s chief general manager, Human Resources: “About 40,000 employees will retire in the next five years. The age profile for officers is 46 and that for clerical staff is 40. The target is to bring down the average age of officers to 40.” Goswami adds that the bank is not aiming to add to its workforce, but only to replace those who are retiring. But with about 8,000 people retiring every year and 4,000 of them officers, finding suitable talent at a time when the bank needs good managers is going to be a tough ask.

“Talent will be key for SBI,” says Sobti. “Will it have the ability to buy talent from outside other than at the entry level—can it get in people at the deputy managing director level?” He thinks the quality of senior managers will, to a large extent, determine how the bank moves forward. “There is no concept of ESOPs. That would have ensured employees have a long-term commitment to the bank. You could, for instance, look at ESOPs which mature on retirement,” he adds.

Bhattacharya concedes that acquiring talent is a major challenge. “Getting people from outside is a problem, and those who are coming are only from the public sector. We are paying more than the market at lower levels, but after that it is very difficult. We need knowledge and managerial skills. To develop that very quickly you need much more effort now than earlier. What could earlier be achieved in 20 years is now needed in 10-12 years. So it’s tough,” she says.

One way in which the bank aims to tackle the human resources problem is by embracing technology in a greater way, both for putting the right person in the right role and also for improving productivity. Technology will also help the bank utilise staff optimally. Currently, internet banking accounts for 36 percent of SBI’s transactions. The bank aims to move this number to 50 percent over the next two to three years. Once that is done, the average productivity of the employees will also go up.

Training and skill development for the 40,000 who will come into the bank over the next five years will also be a priority. “The key elements will be products, process and people,” she says. “While processes will be technology driven, so will people.”

To that end, the bank is putting in place technology-backed HR initiatives. It could be to assess whether an employee has completed a certain level of training or needs further skill enhancement or even for incentivisation, placements and overall talent management.

“We have a SAP module on our HR management system but need to see the scope of what it can do. Over a period, we need to do things on the basis of facts, capabilities and assessed potential and not on the basis of corridor talk which is what happens in a very large organisation,” points out Bhattacharya candidly. “How do I reduce the subjectivity and make it more objective? How do I ensure the best of the best get pushed up?”

But technology is only one part of the change she is seeking to drive. The bigger challenge is to achieve a larger cultural makeover, and get that to stem from the rank and file. For that, mere technology is not going to be enough. Communication, she says, will now be a key element of life at SBI. And one important step towards that has been an internal blog—called Aspirations—which the bank has launched. Already, the blog has become popular and several new ideas are coming up from employees across the board. Bhattacharya apart, several chief general managers and deputy general managers also have begun blogging. “Recently, we moved the blog to mobile. Communication and participation will be central themes now,” Bhattacharya says.

Some of the action points Bhattacharya is proposing on communication, technology and HR may yet be unfamiliar to a bank known to the outside world as a stodgy giant with a massive balance sheet but a legacy which is turning out to be more of a hindrance than a help. Consider that Bhattacharya’s efforts are not the first instance of a new chairman’s attempts to leave an imprint on the bank. However, the limited tenure given to them has meant that there is often a serious lack of continuity.

Unlike other PSBs where top management is often brought in from rival state-owned players, SBI has believed in bringing in one of their own to the corner room. While the bank believes it has a distinct culture and hence a State Banker would be ideal for the top job, it is also acutely aware that a workforce of over two lakh may not take kindly to an outsider.

S Vishvanathan, managing director in charge of associates and subsidiaries who was himself a contender for the top job along with Bhattacharya, feels having an internal candidate for chairman is better. “They [internal chairmen] understand the culture of the bank and so in a way even if these managers get three years at the top, it is almost equivalent to six years of the CMD of other PSBs,” he says.

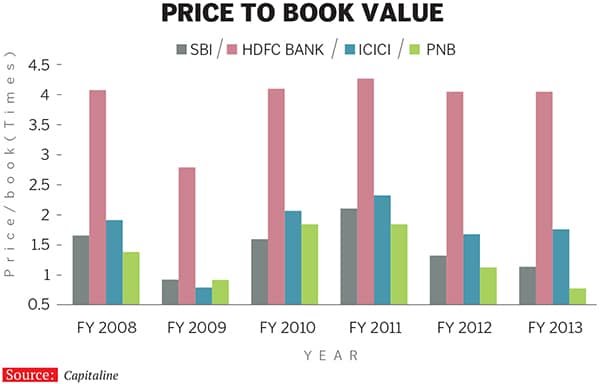

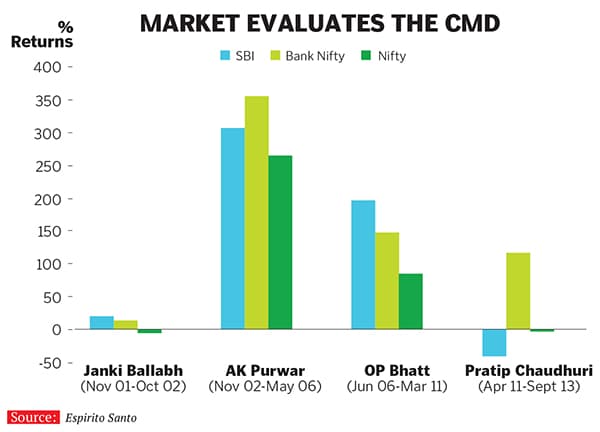

But even so, every chief executive has sought to bring in a distinct management style, a diversity that proves ineffective given their short tenure. In a detailed 2012 report on governance in state-owned banks, broking firm Espirito Santo Securities points out that the tenures of various CMDs at such banks have often had a telling impact on their stock market performance as management styles differed.

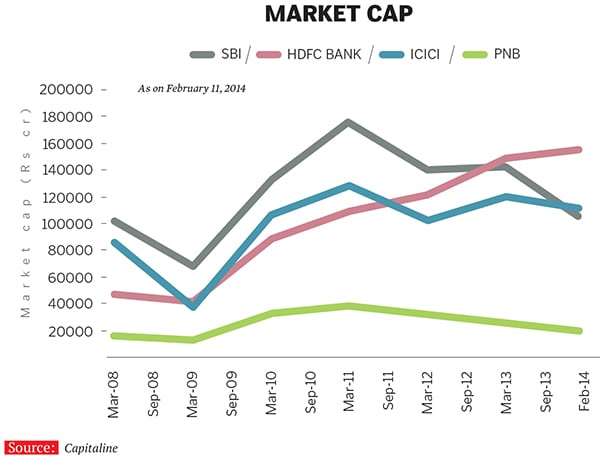

For instance, the tenure of OP Bhatt as SBI chairman from June 2006 to March 2011—the longest in recent times—was characterised by high growth in the loan book (CAGR of 24 percent) and the stock market loved that, with the stock outperforming the Bank Nifty by a hefty 50 percent. This was in sharp contrast to the tenure of the previous chairman AK Purwar, who led the bank from November 2002 to May 2006, a period in which the bank underperformed the Bank Nifty by 50 percent. However, Bhatt’s high-growth strategy caused its own set of problems, leading to asset quality pressures towards the end of his tenure. Pratip Chaudhuri, who succeeded Bhatt, had to deal with subsequent balance sheet issues.

Nevertheless, the fact that the government has given a clean three-year term to Bhattacharya irrespective of when she retires is being seen as a good first step towards ensuring greater stability at the top.

As Sobti points out, “The longevity of CEO tenures is a very important aspect. Look at the work done by CEOs like Aditya Puri [HDFC Bank], KV Kamath [ICICI Bank] and even PJ Nayak [Axis Bank]. CEOs should have at least five years to see their plans to fruition. But the three years given to the new SBI chairman is a good beginning.”

What will be the new SBI chief’s management style? Bhattacharya says NPA management, HR and communications will be the three major pillars her strategy will be based on, with technology as a common thread running across all segments of the bank.

“Other than the various roles I performed at the bank, I have also been to various locations across the length and breadth of the country. I have been able to observe the strengths and challenges. To that extent, it has been a very good preparation for this role,” she says.

Her stint at SBI Capital Markets, the non-banking finance arm of the bank, has also helped her get an external view. Rather than always looking at the loan component, at SBICap she was exposed to the various ways a project could be financed—debt, pure equity and a hybrid of the two. “I would certainly like to see if that can be tried out in the bank,” she says.

Despite the obvious problems on the stressed assets front, one major advantage for the bank is its diversified loan portfolio across sectors. Retail lending accounts for 19 percent of its book. While the mid-corporate segment has another 19 percent, the corporate accounts take up 17 percent and agri loans 10 percent. The bank is also developing new products aimed at reducing the stresses faced by it by increasing customer contact, Bhattacharya says, without divulging much else. “When we are ready, we will unveil them.”

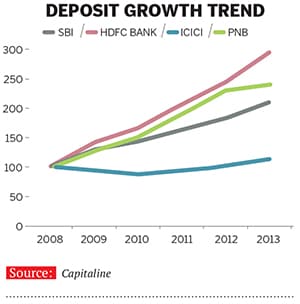

The agri loans side has been a better story because of the monsoon this year, and the bank is also throwing a lot of its might on the retail business which is both safer and more effort-elastic. Home loans account for 58 percent of the bank’s retail book and as much as 77 percent of its home loans are in the under-Rs 30 lakh category. With the home loans book growing, SBI is now narrowing the gap with market leader HDFC and has a 26 percent market share.

Bhattacharya does not want to speculate on where the Rs 17 lakh-crore balance sheet will stand three years from now. Instead, she says this is a period of consolidation at SBI. Business will increase at 15-16 percent, in line with the industry, but SBI will not be chasing growth as the top priority. “I am not aggressively looking at growth; it will happen and when it happens we will definitely be there. But at this point of time what we need to do is have a bit of consolidation and then go up,” she says.

Acutely aware of the enormity of the task at hand and also of the size of the bank she leads, Bhattacharya likens SBI to a battleship which takes 50 miles to make a turn.

Does consolidation mean reducing the balance sheet size like Chanda Kochhar did at ICICI Bank a few years ago? Bhattacharya says that is not the way she would go about it. “I will not be curtailing the balance sheet, because once you pull down something, putting it up again is a problem. These are not things you can switch on and switch off at the drop of a hat. If there are good and safe growth opportunities, why shouldn’t we be there?”she says. “It’s like repairing a running car. I am not going to stop the car in order to repair it. It’s got to keep running. While it is on the go, we will make whatever changes are necessary.”

For now, despite the pressures, the markets appear to be buying into the SBI story. The key strengths giving comfort to the markets are the bank’s strong current account, savings account (CASA) ratio of 43.89 percent and its strong capital adequacy ratio of 13.27 percent. While the government pumped in Rs 2,000 crore into the bank in January through a preferential allotment, SBI also raised another Rs 8,032 crore via a qualified institutional placement (QIP) issue. This brought the government’s stake down from 63 percent to 58.6 percent. The robust growth in net interest income (NII) of 13.1 percent in the December quarter and a growing domestic net interest margin (NIM) have also given some comfort to shareholders and analysts. Though operating expenses have been increasing, the cost of funds has remained relatively under control at around 6.4 percent.

“SBI’s low cost of funds is the reason why the business is sustainable. But the NPAs apart, its operating expenses are one of the highest in the industry. The bank has to figure out a way to cut its costs in terms of salaries and even things like guest houses,” says a leading fund manager who has pegged SBI as a top holding for a long time. Bhattacharya, on her part, is also keeping a close watch on costs.

Meanwhile, the familiar problem of asset quality is where the concerns will continue to lie in the future. “The bank has witnessed elevated asset quality pressures for quite some time now. Given the weak macro environment, we remain cautious on the incremental asset quality pressures for the bank,” says Angel Broking in a report after the bank’s second quarter showing.

The broking firm isn’t being unduly pessimistic. Asset quality concerns weigh heavy on the future outlook not just for SBI but also for Indian banks in general. “We expect weakness in banks’ asset quality to persist for the next 12 months because the economic recovery is likely to be tepid, and it will take time for the domestic industry to recover and corporate balance sheet leverage to decline,” says Standard & Poor’s credit analyst Amit Pandey in a report titled ‘India Banking Outlook 2014: Little Respite in Sight’.

There are those, however, who are still betting on SBI despite the problems. Kotak Institutional Equities, for instance, justifies its positive view on SBI, pointing to its flexible business model on growth and a strong liability franchise which allows it to conduct its businesses profitably.

Sobti believes SBI has several strengths that can be leveraged: Cash management and treasury are two such areas. “If SBI decides to flex its muscles, it can make a huge difference. On the treasury side too, it has massive strengths in positions and can quote aggressively if it wants to,” he says.

SBI has also never really concentrated on cross-selling despite having a line of retail products. The bank now plans to concentrate on this area. This could give a serious boost to its fee-based income. It’s a strategy that successful banks have adopted—their fee-based income has contributed as much as 30-40 percent to their total income.

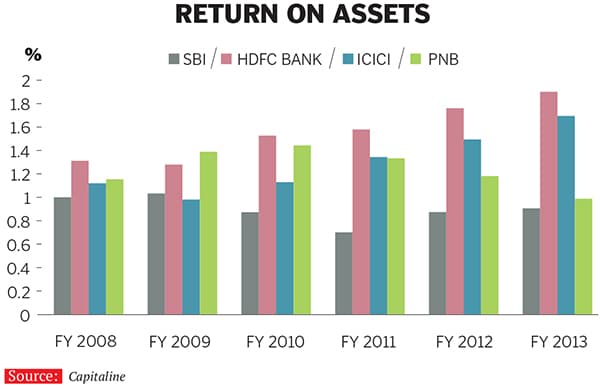

At this point, with the hit in profits, some key parameters like return on equity (RoE) and return on assets have also taken a beating, with RoE slipping by a sharp 670 bps year-on-year for the first nine months of the fiscal. “If profitability is down, these ratios will also be down. Unless I can return to the growth path of profitability, it will be difficult. But having said that, we are very aware and conscious of it. We will learn from the experience we’ve had, contain that and go ahead,” Bhattacharya says.

Three years hence, will she also be joining the ranks of her other predecessors who wanted to make the elephant called SBI dance, but failed to make the changes last? “That depends on the people,” says Bhattacharya with a smile. “If they want to break it [the trend], it will happen. If I want it, nothing may happen, but if they want it change will happen. It’s for them to want it.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)