Reconstructing Indian Hockey

Michael Nobbs is rebuilding Indian hockey. But first, he had to destroy it

In the future, sports historians will mark February 26, 2012, as the day Indians rediscovered their national sport.

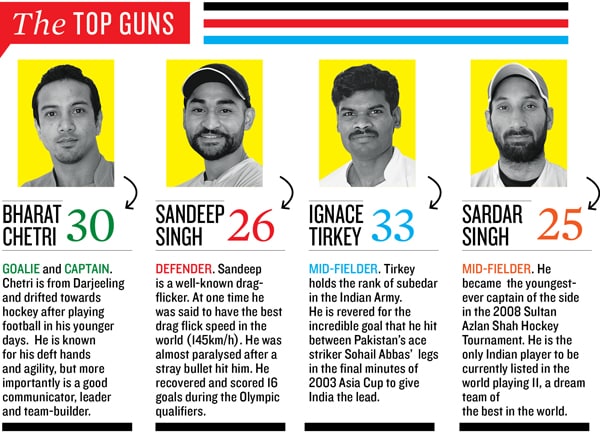

On that day, at the National Stadium, Delhi, the crowd was delirious, jumping, screaming for Sandeep and Sardara, Bharat and Sunil, as if they were Tendulkar or Dhoni. With every goal India scored against France, the excitement rose another notch. When the game ended, and India had qualified for the Olympics, the crowd was in sporting nirvana. A placard captured the mood: Cricket: Zero/Hockey: Hero.

The media joined in, albeit in lower key. The Times of India’s front page said ‘Gr8 show’ (India scored eight goals in the finals). The Asian Age was as exuberant: ‘London, here we come.’ The Hindu, more sedate, said, ‘India’s Olympic dream rekindled.’

All this for hockey? For a sport whose glories people only talked of in the past tense, in the wistful tone they used when they referred to trams and cabinet-sized valve radios? Sure, Indian hockey was the stuff of legend. Hockey historian K Arumugham says that in 1928, when the Indian team was on its way to Amsterdam, they played a series of exhibition matches in England. Seeing its calibre, England decided not to field a team for the Olympics as “they did not want to lose to a slave country”. Between 1928 and 1956, India won six Olympic gold medals in a row, followed by a silver in ’60 and gold again in ’64. As the world caught up, India could only manage bronze in ’68 and ’72, and, aided by a big Western boycott, an eighth gold in the 1980 Moscow Olympics. Since then, the team hasn’t got near the podium.

Economists are familiar with the phenomenon. Companies that once revolutionised and dominated new industries—Xerox in copiers or Polaroid in instant photography—saw dominance vanish and profits fall as rivals launched improved designs or cut manufacturing costs. Technology advances too, making one-time giants obsolete: Wax cylinders gave way to records, which ceded ground to spool decks, which then were replaced by smaller cassette tapes, which were in their turn replaced by compact discs, which lost out to MP3 players, which are now losing out to do-everything phones.

Clayton Christensen, a leading management thinker, studied over a 1,000 companies across 15 industries, and concluded that even the best-run and most widely admired of them were unable to sustain market-beating levels of performance for more than 10-15 years.

Is decline inevitable? Over the last century, there has been consensus on the solution. But the prescription is a difficult one. In the 1940s, Joseph Schumpeter, an Austrian economist, gave it a name: Creative destruction. Old processes, old ways of thinking, old industries—they must make way for the new.

The crowd at the National Stadium saw a team with newfound confidence. What they didn’t know was that they were witnessing the results of a creative destruction exercise. And that the man responsible was a soft-spoken, laid-back Australian, Michael Nobbs.

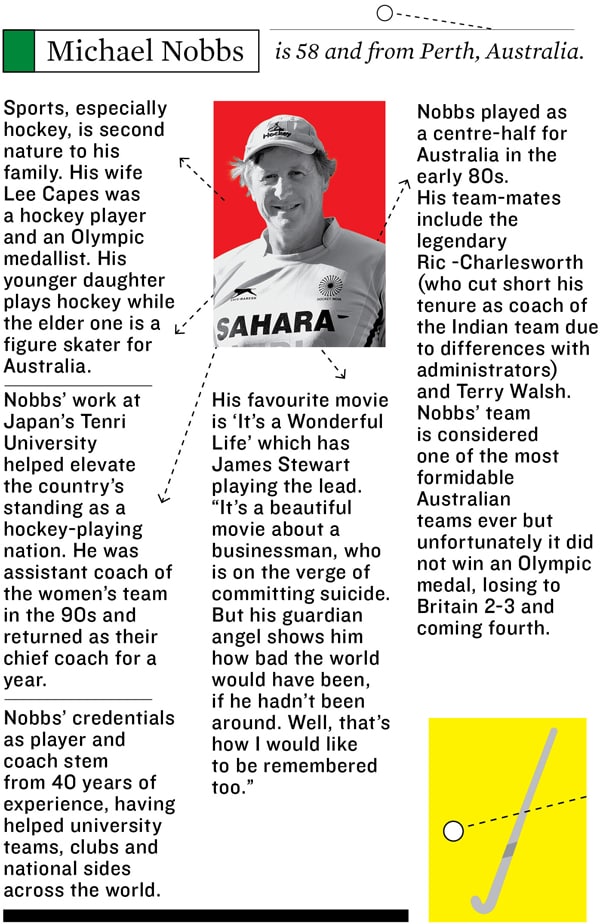

Nobbs is 58, six feet tall. He never seems to be in a hurry, but when you walk with him, you realise that’s just plain deceptive. He makes the simple act of sitting in a chair seem like he’s collapsing into a hammock. He almost never raises his voice, his smile rarely leaves his face. Not exactly your hard-bitten, bellowing, alpha male Hollywood stereotype.

He assumed charge of the Indian team at a particularly tough time: The memory of not having qualified for the Beijing Olympics was still fresh. Add a power struggle between Hockey India and the Indian Hockey Federation for control of the sport in the country. And a team trying to adapt to the European style, which emphasised defence; they seemed to be getting the hang of it, but in tournaments, they were mostly getting trounced.

To Nobbs, this was bizarre. He had grown up admiring Indian hockey’s aggression, its flair and flow. He’d first seen it as a boy, watching Anglo-Indian immigrants play, and he still remembers watching India play Pakistan: “It was pure magic!”

The deficiency, as he saw it, was not in skill but in fitness. You just have to place an average Indian player next to an average European or Australian player to see this. Fix that problem, and India can rule the astroturf. He wasn’t the first to have that insight. But, as every businessperson knows, insight is nothing without execution. And that is where the Nobbs story really begins—and ours.

A Licence to Kill

A little less than a year ago, when Nobbs took over as coach, he planned to build a team that had the right mix of the experience that comes from age and the raw energy of youth. India, however, went by different rules. The corridors of sports administration offices are filled with stories of parochialism and connections trumping ability and performance. State federations are mostly fiefdoms controlled by local politicians who lobby hard to ensure that ‘their’ players make it into the national squad, thereby cementing their places.

And it’s not that talent doesn’t exist. Ask Dr Richard ‘Ric’ Charlesworth. “The talent in India is amazing. I had a pool of 3,000 good players to choose from; Australia had 50. But the administration is very problematic. It’s the one thing that holds India back. You have the potential to be number one.”

Charlesworth should know. He is a sporting legend who excelled in cricket (where he played at the state level) and hockey (where he played for Australia), and became a highly-regarded hockey coach. From 2007 to 2009, he worked as technical advisor to the Indian team, before resigning, fed up of the red tape and unpaid salary arrears. Now, he is back in Australia, head coach of the men’s team, where, “I decide what’s done. The money, the allocation of resources, is transparent and everyone can see how it works and where the money went. It was impossible to work that out in India.”

Nobbs knew all this. When he made his presentation to Hockey India—after Jose Brasa, India’s previous coach, quit—he made it clear that if he came on board, he’d run the place “like a dictator” for the first five years. He would be open to suggestions, naturally, but the final call would be his.

The selection committee saw in Nobbs not just a man with credentials (he had played hockey for his country, and had coached Australian clubs and the Japans’ women’s hockey team), but someone who genuinely admired the Indian style of hockey. And he put his money where his mouth was: He told them that part of his compensation ought to be based on what he delivers. (After India qualified for the Olympics, he got a 10 percent salary hike.)

His selection was unanimous.

That, Nobbs knew, was the easy part. He knew the system would fight back. His weapons were hard facts and reason. When he proposed a player to the selectors, he backed his choice with statistics, with video clippings demonstrating skills, and so on.

He selected players on the basis of the skill sets he wanted from them. Experience was not as important as the ability to fit into the larger game plan; he axed senior players like Arjun Halappa and Rajpal Singh. He shrugs: “It had to be done.” In came promising youngsters like Birendra Lakra, Danish Mujtaba, SK Uthappa, Kothajit Singh and Yuvraj Walmiki almost all of whom were his finds, none of whom had worn India colours before.

Getting the players he wanted was one thing; retaining them turned out to be an issue too. When Sandeep Singh, the star drag-flicker of the team, and ace mid-fielder Sardar Singh decided to play World Series Hockey and leave the squad, Nobbs decided to go ahead without them. Halfway through their commitment with the WSH, they realised that their futures lay with the national team. Nobbs was clear that their return must be on his terms, not theirs. “I told them that if they were to return to the national team, they should do so for reasons other than money.”

Showing Them the Money

Indian hockey players aren’t even paid match fees. Thus far, the system has been patronage-based: The government rewards players on the national team by offering them jobs with the state police force, the Army or public sector undertakings. Sure, they get job security, but however well they perform, there is little chance of them getting anything close to the amounts that even mediocre IPL players make.

Ric Charlesworth lost this battle. He remembers putting together a list of 10 things he wanted the authorities to do. “Number one on the list was that everyone on the contract would get paid. We didn’t get to number two. It was impossible to get anyone to make a decision. No one knew where the money went.”

And you can forget about adulation. Sandeep Singh, despite many awards, can walk down most streets without being recognised, let alone mobbed. A coach with the team, who has known him for more than 10 years, remembers Sandeep visiting his college in Punjab after the team had won a major international tournament: “I was astonished to find Sandeep waiting for me in the corridor and people passing by without recognising him.”

That’s changing. One day, while we were spending time with the team, on the street outside the Sports Authority of India (SAI) stadium, a boy ran up to him, shook his hand and said, “Sandeepbhai, amazing performance at the qualifier! Please continue with the performance at the Olympics!” Sandeep Singh rarely smiles; but that time, he thanked the lad and his grin spread from ear to ear.

And Nobbs hasn’t given up on the cash. From what we hear, he’s close to having his way on match fees for the players.

iBelieve

Australia has a reputation for marrying passion for sports with a scientific approach. David John, also Australian, and part of the Nobbs core team, says that the sports authorities in Australia employ over 80 people with doctorate degrees in nutrition; in India, he hasn’t met a single one yet.

Nobbs is an engineer by training and a big Steve Jobs fan. He looks for ways to use technology to get better results. He persuaded Hockey India to give every player an iPad; he’s now training the players to use the device to study their game and those of their competitors.

“But,” he says, “it’s not just about science. It’s also about the story. It’s in making every team member believe in the same story.”

The story he’s convinced everyone to believe in is that they have to break into the top six. “We are more confident of our game, skill and physical capabilities than ever before,” says Bharat Chetri, the team’s affable captain. Once you’re at that stage, the differences between teams are minor. As two-time Olympian MM Somaiya says, “It’s anybody’s game on a good day.”

It also helps that Nobbs, like Jobs, knows how to say no. “It’s only by saying no that you can concentrate on the things that are really important.” When Steve Jobs returned to Apple, one of the first things he did was cut down the product line and focus the company’s attention on where he saw its future lie; Apple’s turnaround is as much about what Jobs chose not to do.

Nobbs decided that his A team wouldn’t play every tournament. His reasoning: There are only five or six big tournaments which give a real push to a team’s ranking. The national team should focus on winning those critical tournaments, leaving the rest to the junior team, so they get exposure.

Adapt, Evolve

In 1998, the International Hockey federation (IHF) changed some of the rules. It allowed players to be rotated, and play on the offside as well. The best teams in the game reacted by beginning to rotate players efficiently. They played all out, took breaks, then came back fresh to play hard again. India, on the other hand continued to let their best players be in the field for as long as it was possible.

Part of it was belief in natural talent and brute force; and part was unwillingness to trample on the egos of senior players.

In the Nobbs regime, everyone has to follow his schedule. “Every player gets to play for six minutes and then rests for three minutes before going back. This is also in a sense a leveller where the lines between senior and junior get blurred and everybody performs at their best.”

‘Total hockey’ is the new mantra. Every player is expected to play every position. Where once defenders would pass the ball up-field, then stroll around until the opponents made the next attack, they now charge up and play an offensive role in the attack as well. This demands not just skill, but strength, stamina and speed.

Nobbs’s attention, therefore, is now focussed on raising the team’s fitness levels.

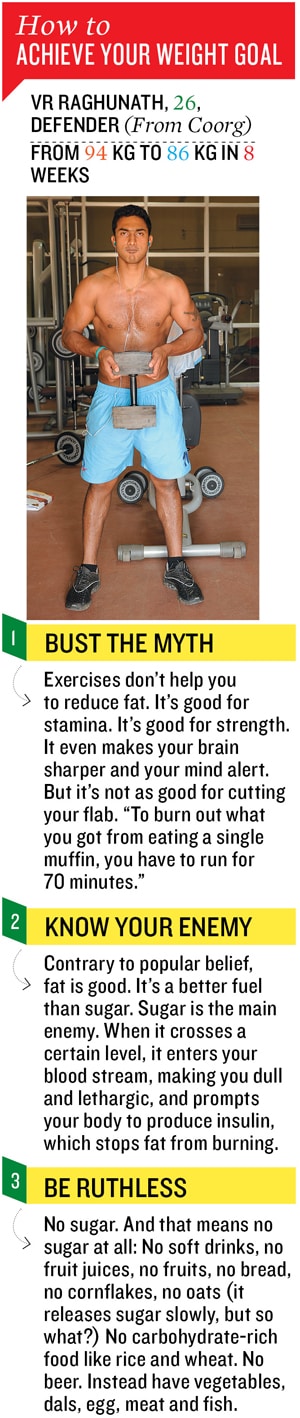

Before, the players hadn’t done much beyond just running a lot. Now, it’s all about exercising the right muscles (which would vary from player to player depending on the position), eating right, and having a positive attitude.

If You Don’t Measure, How Do You Know You’ve Improved?

Before Nobbs came in, the Indian team was trying to change to the European-style hockey. This was partly because the previous coach was European, but also because of the perceived failure of the Indian style: If European teams were beating us, they must be right. Nobbs disagreed. European defence, he said, was just a reaction to the South Asian style. “The problem is not with your style, but with your ability to execute it.”

Nobbs sold a story of hope, of confidence, of winning an Olympic gold by 2016. But to believe in that story and put in the long-term work, the players had to see perceptible gains in the short term. Of course, one metric is winning tournaments; the team has won three out of the four it played under him. But his methods also see daily improvements.

Take VR Raghunath. At 94 kilos, he was overweight, and it was telling in his performance; he was close to being dropped. Nobbs dared him to lose five kilos, and promised him to give any help he wanted. Raghu picked up the gauntlet: “Why five? I’ll cut eight!” Nobbs and John customised a diet for him, which ruthlessly slashed Indian staples like rice, chappatis and potatoes—says John, “It’s wiser to get your fuel from fat, not carbohydrates”—and in two months, he lost eight kilos.

Everything is measured. Intake, output, even breath. This structured approach has instilled discipline. (And when they ignored the rigour, it showed: In a recent match against Belgium, some players didn’t follow the schedule and stayed on the field longer; they lost.)

Dealing with failure is another thing Nobbs has taught them. No one wins them all, and your failures, when they happen, are part of your growth. Shake off your blunders; look forward.

The Gospel According to Michael

Perhaps it was the weather—the sun was blazing, Bangalore’s famed breezes were blocked by the Sports Authority of India building on one side and high ground on the other three. Perchance they were tired; they had an intense session of pumping iron and sprinting on loose sand that morning. Perhaps, on that particular evening, the fighting spirit had coalesced into defiance. It could be that they were fed up of a media that had time only for cricket, and we, asking them to pose for a magazine picture, were a convenient target for their angst. This much was clear: Team India, to a man, wasn’t keen on a photo shoot. When our photo chief asked them to walk the 100-odd metres to the spot he’d chosen, they frowned, raised their eyebrows, muttered complaints among themselves, dragged their feet, held their hockey-sticks like walking canes.

Then, Nobbs walked up, a faint smile on his face, eyes twinkling, and said six words: “Let’s f*****g finish the shoot first.”

Silence.

One could hear the rustling of the leaves, a car in the distance. Slowly, the defiance drained out of their faces. We got our shot.

We weren’t surprised. Nobbs, we knew by then, doesn’t have to yell to be heard. He has earned the respect of his players, giving them a vision, showing them the way, helping them get better, being with them at every step.

But will that lead to a good show in Olympics? Some are unconvinced. Charlesworth, for one: “Where the Indians are right now, I’d be happy if they make it into the Top 12.”

But there are three more months to go. Every day, they get a little better. In just the 10 days we spent with them, we could see some of the progress. Nothing big: Maybe just more reps per set in the gym; or confidence levels. Nobbs isn’t over-claiming. It’s too soon for all he’s done to have effect. He knows what he’s building, though: “In 2016, this team will be ready to go for gold.”

What of London? We’re willing to wager: Top six.

(An interview with Michael Nobbs on the next page)

‘Top Athletes Don’t Give Excuses’

Michael Nobbs talks about his links with India and Indians

You seem to have an attachment towards India. Where does this come from?

It comes from my Indian friends, many of whom are hockey players. In the early 1960s Anglo-Indians came to Australia. In the national side there was the Pearce brothers. They played the Olympics and then that became my dream too. Those people have guided my character and hockey too. I also worked for an Indian company Gestetner. Indians have always been popping in and out of my life.

How is it that Australians are so aggressive at sport?

It comes from the competitive nature of sport in Australia. We have a limited population and an intense desire to win. The problem is that people blame everyone else. “I haven’t the right shoes, the facilities aren’t good.” These are all excuses of people with weak character. Necessity is the mother of invention. Top athletes don’t give excuses.

What was India’s game like before the years of decadence?

India-Pakistan games used to be sheer magic. They would keep the crowd enthralled with the sheer brilliance of skills. They had sheer brilliance but nothing else; no stamina. You need to back up skills with character, sports science and nutrition.

Nutrition is an important part of your coaching programme. How do you connect nutrition to player performance?

David John [nutritionist] has invented a measure called indirect calorie meter which measures carbohydrate levels in the body. If your insulin overflows too much it flows into your blood stream. Your eyesight could drop by 20 percent, exhaustion and so on. When you monitor these things, performance improves dramatically. More protein, less carbohydrates, it produces results.

Can Indian hockey return to its days of glory?

Hockey in India made a lot of bad decisions over the last 30 years and cricket did a lot of things right. Hockey can return to the glory days. Everybody loves success. You got an abundance of talent and you don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Toughest thing right now is people’s expectations. We can produce good results and we have so far.

We have won 17 of the last 18 games. We haven’t played the top teams in a while. But we are getting ready for tougher competition. We are going to have to take a few beatings but then we climb up.

Do you think hockey needs marketing?

Yes marketing is a requirement for hockey. In cricket you have great players and we need this in hockey where kids would say “I want to be like Sandeep, I want to be like Sardar.” If we could create heroes in this team, it would be a great thing to do.

Can India win a medal this time?

We are nowhere near where we need to be. We need to manage our expectations. It could happen and sport being sport, anything could happen. But realistically, it’s not going to happen. We have number of tours and training. Compressing so much training into nine months is an intimidating job.

(Additional reporting by Abhishek Raghunath)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)