Paytm Reloaded: It's no longer just a mobile wallet

Founder Vijay Shekhar Sharma aims to make Paytm the biggest one-stop shop for all retail and financial needs

Images: Amit Verma

Images: Amit Verma

Samsung electronics co sells its phones through about 150,000 authorised shops in India. And Paytm Mall, through a collaboration with Samsung that started in November 2017, is bringing all of them onto its online marketplace, giving each one a QR code, and the requisite training and support.

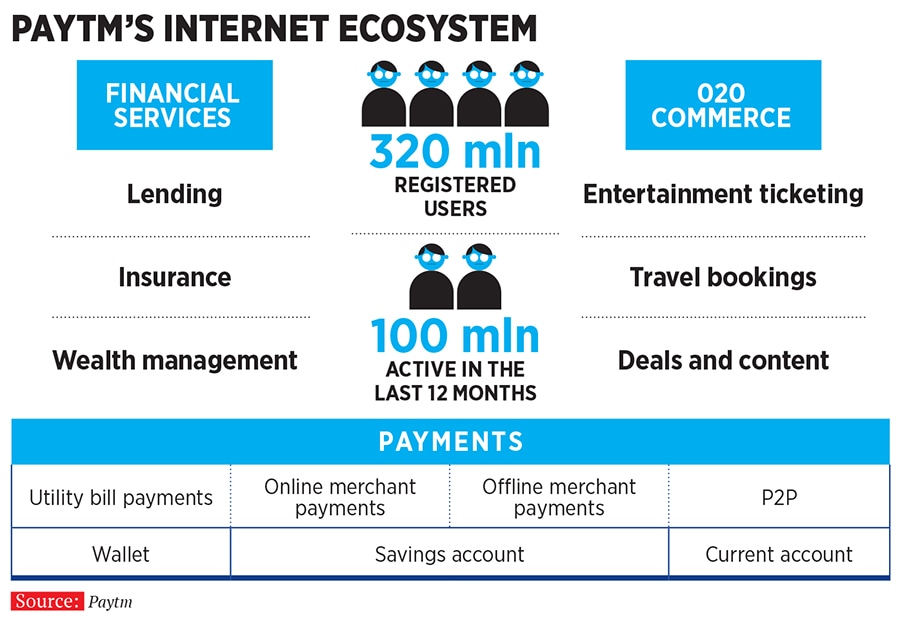

Paytm Mall is the recently formed ecommerce business of One97 Communications, which was separated from the parent to function independently around March-April 2017. Noida-based One97 Communications operates the Paytm mobile wallet. And with backing from China’s Alibaba Group Holding Ltd, and Japan’s SoftBank Group Corp, founder Vijay Shekhar Sharma, 39, has been expanding into online commerce, financial services, including wealth management and insurance, as well as travel and entertainment.

While Samsung is also popular on sites such as Amazon and Flipkart, its massive offline distribution is its strength. However, as online smartphone sales rose in India, it was a challenge for the physical stores to match the offers on ecommerce sites. Getting onto Paytm Mall’s platform meant, be it at a physical retail store or on the online app or website, or even on Samsung’s own online storefront, “the offer is the same”, says Amit Sinha, a vice president at Paytm and COO of its ecommerce business.

“The O2O strategy has been working wonders for us,” says Sinha. O2O refers to ‘offline-to-online’ because Paytm is attempting to connect to the net via its QR codes every ‘offline’ or physical store it can reach.

And not just with Samsung. Red Tape, Khadim’s shoes—the latter particularly famous in Kolkata—and Lenovo laptops are among the many brands that are beginning to tap Paytm Mall to boost their sales.

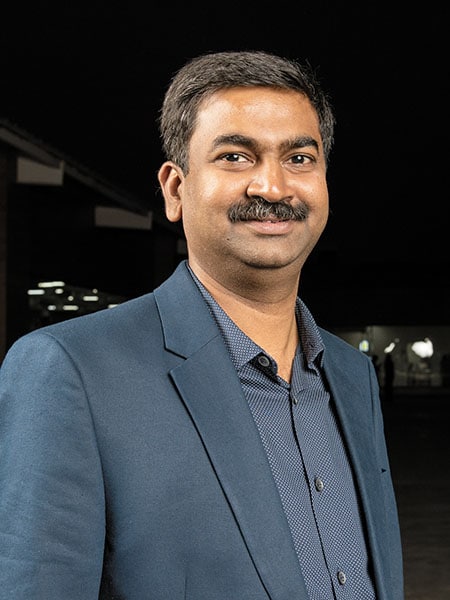

Amit Sinha, COO, Paytm Mall

Amit Sinha, COO, Paytm MallSinha says the ecommerce business, which saw the formal launch of the marketplace in April 2017, doubled its market share to about 14 percent by November. Helped in part by $350-million-plus sales in the 30 to 40 days through Diwali the month before.

In 2017, One97 Communications restructured itself. The mobile wallet service became part of the newly-formed Paytm Payments Bank, which in turn will lead the company’s financial services foray for consumers. And the ecommerce part of selling various products and services—from train and movie tickets to smartphones, air purifiers and washing machines—became part of Paytm Ecommerce Pvt Ltd, a separate company that runs the Paytm Mall online marketplace and mobile app.

“We are raising a large amount of money on the ecommerce side as we speak,” says Sharma settling into an interview with Forbes India. That will make the ecommerce business alone “doubly unicorn”, he adds, and the overall company could be valued as high as $12 billion. That would top Flipkart’s value of $11.6 billion at the time of the Bengaluru rival’s $1.4 billion fund-raise in April 2017, possibly making Paytm India’s most-valued startup. Paytm Mall’s funding deal is expected to conclude soon, he says, but doesn’t add details.

The funding, led by SoftBank, is to the tune of ₹3,000 crore, a person with knowledge of the transaction tells Forbes India, and Paytm Mall will likely raise more money as well.

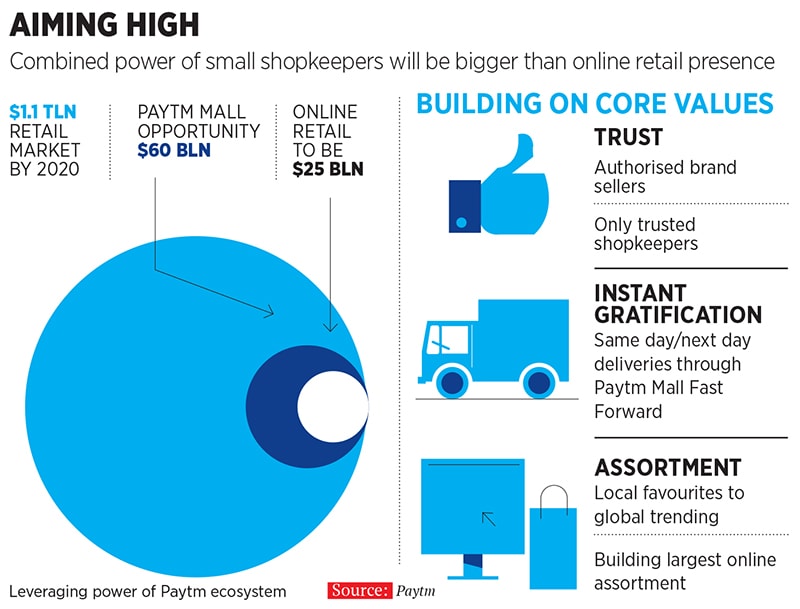

India’s retail scene comprises some 15 million shops, with an overwhelming majority of those being run by individual owners. They lack scale, and have limited inventories, Sinha points out. Paytm plans to offer them a way of eliminating these two obstacles, so that those mom-and-pop stores could do a lot more.

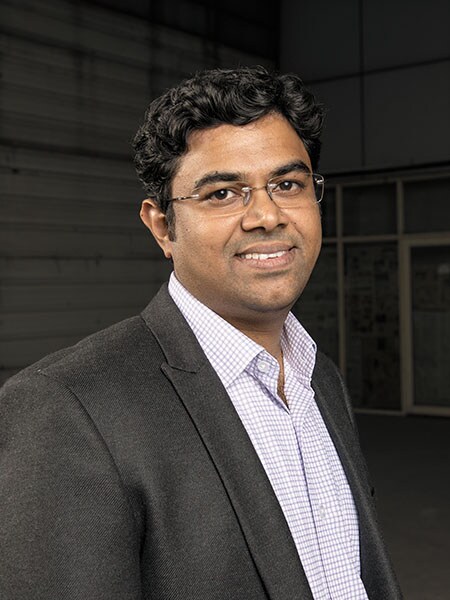

Madhur Deora, CFO, Paytm

Madhur Deora, CFO, PaytmPaytm is digitising them and training them to take orders from consumers both online and at the store. This means, the consumer gets “the same level of service”, Sinha says, that one is used to at large retailers or on ecommerce sites. It includes matching the discounts and offers.

Therefore, there will be millions of points of sales and fulfilment versus a few large warehouses that the big ecommerce sites have. “That is the core belief that we are building on and early results have been really good,” Sinha says.

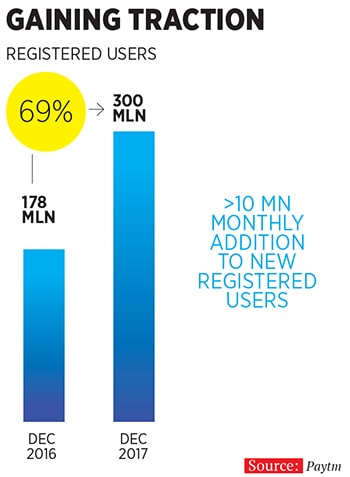

Paytm has over 300 million users and the company processes over 10 million transactions a day, says COO Kiran Vasireddy. It has 6 million merchants on its network. “The key is to reach out to every kind of small and large store to hit 10 million stores by the end of March 2019,” he says.

Loans, not just to consumers but also to sellers, form an intrinsic part of the O2O business as well. Take the case of Samsung phones, for instance. When each of the 150,000 stores becomes an “endless aisle” for the consumer and the seller, Samsung gets to know what is selling where, and deeper analytics facilitate what comes next—quick and on-the-spot loans.

Of the 150,000 stores, only a few thousand have ever been able to offer a loan to a consumer to purchase a fancy smartphone. This was because of the traditional approach of banks that required a staffer to be physically present at the store and offer loans to the buyer, Sinha says.

With Paytm Mall’s network,

each store can offer the same plan from the same seller “and the campaign goes live at the click of a button”, he says. “It’s a deep and symbiotic relationship that we’re getting into with Samsung.”

The importance of the lending effort is underscored by the fact that One97’s CFO himself is charged with running the lending business as well.

Madhur Deora joined One97 and stepped into that position in June 2016. As an investment banking veteran, previously at Citigroup, he already knew Sharma and had worked on the company’s deals, including its important fundraising efforts.

“Offline merchant payments is one of the fastest growing businesses at Paytm,” says Deora. Therefore, whether it’s a consumer who has a track record of honest purchases and minimal returns, or a seller who has been doing “stable” business using Paytm, why should they not get attractive loans, is the logic.

Kiran Vasireddy, COO, Paytm

Kiran Vasireddy, COO, Paytm A ₹10,000 loan for a consumer or a ₹2 lakh loan to a seller would not be smooth the traditional banking way. A Paytm user, however, already has a history of transactions on the platform, and the digital platform is far more amenable to that quick loan, point out Paytm officials. The story is the same when it comes to the merchant. Paytm’s answer for now is to partner with large NBFCs, which provide the loans, and see their portfolio expand, while Paytm brings in the tech platform. Paytm has also, in parallel, built the processes to credit-score its customers and other analytics for rapid processing.

Banking with Paytm

Much of 2017 was spent in building one other important way in which to engage the consumers right from when one receives money from any source—be it salaries or that quick ₹500 borrowed from a friend. This was the Paytm Payments Bank which, within ten months of going operational, has already moved to offer digital and physical debit cards to its customers. When its debit card was launched, “we got orders from 800-plus cities”, says Renu Satti, the bank’s CEO, who has worked with Sharma for over a decade at jobs that included running HR operations.

Though currently most of the bank’s 180 million customers are those who were existing mobile-wallet customers, the bank’s convenience is pulling in new ones too. Paytm requires its savings bank account holders to maintain no minimum balance unlike traditional banks.

Besides, India’s payments bank rules place a ₹100,000 rupee limit on the balance held in an account at a payments bank, at the end of a business day. Paytm is seeking to turn that into an opportunity to offer a simple wealth-management product, by partnering with banks to which excess cash could be moved for more attractive returns. For now, one gets fixed deposits with IndusInd bank. On-demand deposits will soon be started, Satti says.

Paytm Payments Bank is also competing with businesses like Sodexo, with corporate offers. It has added more than 500 businesses that are giving Paytm’s digital food wallets to employees, she says. New packages on reimbursements are in the offing.

The bank will open 100,000 banking outlets along the same lines it is building its O2O network. So, expect your nearby pharmacy or grocery shop to also become your banking-correspondent. Salary accounts are expected to be offered soon, as well.

All this doesn’t mean Paytm will rake in the money anytime soon. “For players such as Paytm, it will take continuous investment to make the payments bank sustainable because the margins are thin in payments,” says Saurabh Tripathi, a senior partner and managing director at Boston Consulting Group.

Further, India as a market offers its own challenges and is no comparison to China, points out Tripathi, an expert in banking and financial services, who has advised clients on large-scale change and digital innovation. It is still quite some way away from being fully or even heavily digitised despite the big changes over the last two years. Large parts of the population still comprise people who are poor and digitally illiterate. “There is a huge difference between India and China. China is so far ahead in terms of digitisation, prosperity,” he says.

While India is adopting digitalisation at a rapid pace, the scale is different compared with China. The number of people carrying out digital transactions in China is considerably more than in India. Therefore we need scale before the same models that are working in China work in India, says Tripathi. “Getting to China’s scale will take time in India, and the payments businesses will have to be patient before they can build strong bottomlines.”

The business case hinges on accumulating a fair amount of data on customers that can be used to cross-sell other products. These include financial products like wealth management and lending as well as non-financial ones, says Tripathi.

An ecosystem play

Beyond the payments bank, the company’s financial services business will extend to lending, insurance and wealth management. Paytm Money, another independent unit like Paytm Mall, will soon start operations, selling mutual funds, The Economic Times reported on March 7, citing the unit’s head.

Paytm wants to be present in everything the consumer wants to do with money—“earn, save and spend”, says Sharma, with deposits and wealth products addressing the first, insurance the second, and the mobile wallet and Paytm Mall for the third.

Sharma has a slide on his phone: A sort of a Venn diagram, but devoid of the intersections of various clusters, that shows the ecosystems being built by Tencent, Amazon, Alibaba and SoftBank in India. It has Paytm in it and some of its rivals. Some have common backers now, he points out.

“Ultimately, India will have an ecosystem of a few companies with this full stack of services for consumers. It’s clear this will be a fight among ecosystems, and no longer between one payments company and another payments company,” says Sharma. “Or another company that is doing payments,” he adds, referring to Facebook’s WhatsApp instant messaging unit, which started offering payments services to some of its 200 million-plus users in India. In mid-February, Sharma went on a tirade on Twitter, criticising how WhatsApp’s foray into payments in India didn’t happen on a level-playing field.

In his office, Sharma downplays the small tweet-storm he touched off: “I thought a company was trying to be too smart; I wasn’t in India, I didn’t get a chance to talk to other people, and (at the end of the day) it was a tweet that ended up becoming a lot more, a lot bigger than a tweet... The conversations about WhatsApp, it got cute.” However, in the end, this isn’t about a payments company fighting another. “No it’s about fight of ecosystems,” he says.

Renu Satti, CEO, Paytm Payments Bank

Renu Satti, CEO, Paytm Payments Bank At the heart of it, payments

That said, Sharma also offers insights into why payments will remain central to Paytm’s plans. They are an important way in which customers will keep coming back to the platform because it’s a high-frequency activity.

“The ecosystem is based on the platform of what the customer is connecting with you for, and how frequently,” says Sharma.

Other ecosystems coming up in the country are “led by commerce” while Paytm banks on payments, he says. The former isn’t as much a high-frequency activity as the latter, and even commerce requires a payments step. On an average, a customer transacted on Paytm in some way about 32 times in 2017, which was nearly double the average in 2016, and the aim is to take it to 30 times a month.

Paytm aspires to be one of those companies with at least a half a billion users, says Sharma. “The journey is long, and our target is, can we have 500 million people using us every month and week of the year. That’s the battle, that’s the chase.”

The local commerce bet, too, isn’t a bet on being a retailer, but one on building a large ecosystem of brands and retailers, which want to reach the consumer on the smartphone, he says. The model is one of partnership, which will win in the long term, Sharma asserts, just as it has worked in China.

Some six to eight months into launching Paytm Mall, the company is already the largest seller of laptops there, he says, and the second largest appliances seller—“tough, commoditised categories”.

Categories such as groceries and FMCG, which are high-frequency areas, thanks to the repeat use of Paytm, give birth to high-repeat shopping also. The company is directly partnering with local shops, brands and their distribution networks. In Navi Mumbai, for instance, or Gurugram, orders are being filled by your local supermarket, he says.

That Alibaba, through its recent investment, has also become an important stakeholder in Bengaluru’s Supermarket Grocery Supplies, which operates the BigBasket online grocery store, opens up avenues for them to partner closely with Paytm Mall.

Sharma adds that just like Amazon or Tencent, which continue to expand massive ecosystems of multiple products and services, Paytm will build its own in India—ergo everything from ecommerce to life insurance to one of Sharma’s favourite initiatives, which is O2O.

Net contribution positive

Excluding the commerce business, which is fairly new, at the consolidated Paytm level, “we are net contribution positive, already”, says Sharma. That means, the 300 million or so transactions the company is processing every month—with the volume of transactions in the range of $1.3 billion to $1.4 billion a month—are making money “net of payments costs, marketing and cash-back costs”.

“We are making money if we take these costs into account and at the scale that we are talking about. We have only two costs left—staff and office,” Sharma says.

He asserts that even with Paytm Mall, his costs are lower than those of his biggest competitors. One reason is that Paytm Mall has no warehouses of its own, “and we also have multi-party contributions”, to the cash-back and other discounts, he says.

Clever use of technology is another. “We are able to predict on the fly, whether you’re going to cancel this flight ticket or bus ticket or not,” says Sharma. Because Paytm knows what you’ve bought, and what your phone is behaving like right now. Therefore, says Sharma, “we can offer products such as cancellation insurance very coolly to others… okay nobody knows this, but Paytm sells 2 million insurance policies a month right now,” which users can buy from a host of insurers listed on Paytm. This includes, for instance, insurance with train tickets. “Insurance is a big business for us, scaling fast,” says Sharma.

Paytm is also seeking regulatory go-aheads for its own foray into life and general insurance. It has also become the second-largest movie ticket seller and the second-largest travel booking company, he says.

Shankar Nath, CMO, Paytm

Shankar Nath, CMO, Paytm The way ahead

The entry of SoftBank has made a big difference in India’s ecommerce market. Sharma doesn’t comment on their strategy, but points out that the landscape will change a lot by 2020, in India. “Basically, India can’t be a multi-horse game for long,” he says. However, it will take those three or four years for the dominant ecosystems to emerge, and it won’t easily be a winner-takes-it-all market. That means “in some areas we will be the challengers, and in some places, we will be challenged, but I think India is too important a market to be ignored by anyone”.

Industry analysts concur: “If you look at the e-tailing industry, it is consolidating among these three players—Amazon, Flipkart and Paytm,” says Ujjwal Chaudhry, engagement manager and head of e-tailing practice at RedSeer Management Consulting in Bengaluru. “While the first two have the largest share, Paytm Mall has seen the most growth, albeit on a smaller base.”

While Paytm believes dominant ecosystems will consolidate the categories, “We still think it will be a category by category play,” says Chaudhry. Cash-back offers currently work as a strong enticement, and while Paytm has made large strides in areas such as movie ticketing, for instance, “it remains to be seen if they can convert people into other services,” he adds.

The many changes happening in India today are still only “the preface to a 28-chapter book that is right now being written”, said Sanjay Swami, a managing partner at Bengaluru’s Prime Venture Partners, a VC firm that has a strong fintech portfolio. He was responding to a question on how the Amazon-Flipkart-Paytm competition might play out, at a press conference in Bengaluru recently to announce the firm’s third fund. “A lot is going to happen… there will be some big companies that don’t exist today that will be created.”

That means there will be unprecedented levels of resources pumped in and “incredible” technology-based experiments will be tried out—far different from what has happened in the US or China, Sharma says. In America, the dominating players were decided in the desktop era itself, and in China, the new players of the mobile era have taken charge.

India, on the other hand, is seeing a “potpourri” emerge, with mobile internet leading the charge, but it’s a market where the desktop is also present, and, unlike in China, international competitors are thriving.

“ The key is to reach out to every kind of small and large store to hit 10 million stores by the end of March 2019.”

In commerce, the online marketplace will overtake the retail model and that is the time Paytm would look at its options, says Sharma. There are potted plants in the conference room, aimed at cleaning up the air inside. Outside, a young staffer takes snapshots of the readings on strategically placed air purifiers. That employee “reports back to me”, Sharma says. “I’m trying to create a cocoon around me and my friends and staff and their families... when you come to office, there should be superior air quality, that is my commitment.”

However, outside, there is no cocoon against the onslaught of competition from Flipkart, which too has big financial services operations planned, led by its PhonePe unit. Or from Amazon, which has become an entrenched ecommerce player in India, with its Prime services trusted by millions.

Sharma’s way is via payments, and via the O2O network. “I acquire customers on payments, I don’t make money on them, but I make money on commerce and financial services,” he says.

Profitability, however, won’t be on the horizon until Paytm can hit its 500 million customers target. “Maybe you’ll start seeing traces of that beyond 300 million or 400 million. It’s a huge market, so can’t leave any significant set of customers on the table,” says Sharma.

Once upon a time, Sharma had considered an IPO, when his was a much smaller venture. That he walked away from the plan has proved fortunate, with the kind of deep-pocketed and experienced backers that One97 has found now.

The private investors are so strong and invested strategically in Paytm’s success that there’s really no need for an IPO, he says. He would rather make the company a “very mature private company” first.

The company has about 16,000 full-time staff, with roughly one in four of them being engineers. At this size, worries are already not that of a startup, but of a larger enterprise. “The unknowns like people playing dirty, or sudden regulatory changes worry me,” he says.

Everything else he seems to take in his stride. Compared with two years ago, or even a year ago, he says, “I would have never expected that we would be doing insurance at the scale that we are doing now, and what our plans would be,” Sharma says. “Today, in India, you can build something world-class, made in India, which can go places. This is what excites me every day now—an opportunity to create a new financial services model that can go out of India and show to the world that this is how it is done,” he says.

It’s also about taking risks. An early bet Paytm took has paid off handsomely in raising the profile of the startup. “We bet the house,” says CMO Shankar Nath, of the over ₹203 crore that they spent in 2015 to win title sponsorship for all cricket matches played in India administered by the Board of Control for Cricket in India for four years through 2019. At that point, it was a big sum for Paytm, but not so much today.

Paytm’s is a “world-first” model, Sharma says, and it might still be a moon shot, but his dream is to see its logo rub shoulders with those of the biggest companies in the world. He is unabashedly inspired by Deepak Parekh’s success at HDFC, he says.

“They are a bank, a mutual fund, an insurer,” says Sharma who nurses an ambition to make Paytm’s financial services the HDFC of the mobile internet age in India. After the interview, Sharma kicked off the Friday evening with one of his favourite songs: Coldplay’s ‘A head full of dreams’.

With inputs from Sayan Chakraborty

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)