It is Trying to Rebuild Its Image, But Can Vedanta Find its Soul?

Charges of environmental damage and human rights violations are forcing Vedanta group to change. Founder Anil Agarwal has to ensure the changes are more than cosmetic

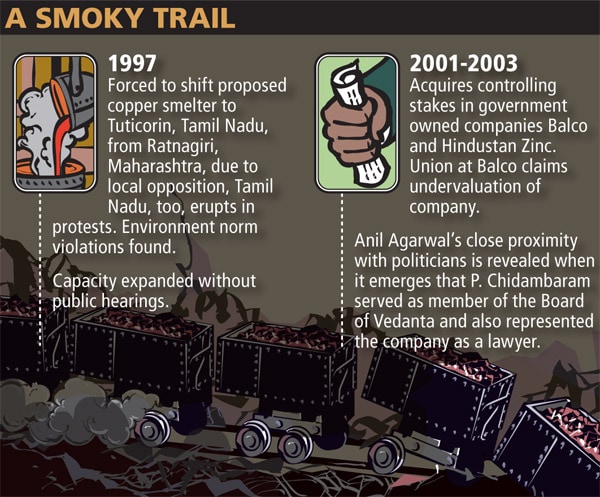

There is a conspiracy theory making rounds in the southern seaside town of Tuticorin, where metals company Sterlite Industries set up its copper smelter 13 years ago, after being driven out of Ratnagiri, Maharashtra, on environmental grounds. Some people claim that Sterlite lets out gallons of effluents into the sea, but not directly. They say it has linked up its drainage pipes to those of another well-known company in the area, which eventually pours the effluents into the sea.

Forbes India asked Vedanta Resources plc, the holding company of London-based billionaire Anil Agarwal’s $6 billion plus group that includes Sterlite, whether there is any truth in the prattle, but got no reply. The Tuticorin plant, which began operations against fierce opposition from local environmentalists, has never been able to fully erase such doubts.

It is a similar problem that surrounds Vedanta’s project in the middle of tribal territory in Orissa to mine for bauxite, the raw material for aluminium. It is part of Agarwal’s most ambitious plan for an integrated aluminium plant. Not everyone is convinced it is a good plan. High profile investors including the Pension Fund of Norway, and the Church of England, sold their shareholding in Vedanta citing environmental concerns and human right violations at the upcoming plant. India’s ministry of forest and environment found the company had violated the rights of forest-dwelling people in pushing through the project. Groups such as Survival International, Amnesty and ActionAid, have pounded the company with similar allegations.

Controversy is not new to Agarwal, a 56-year-old businessman from Patna who started his career bringing together a variety of family businesses nearly 35 years ago. In fact, he thrives on them, having become known more for running some of the world’s lowest cost producers of various metals and minerals than for running eco-friendly plants.

But with his increasingly globalising business now listed on the London Stock Exchange, he is facing more scrutiny outside his homeland where implementation of environmental standards could be lax. At Vedanta’s head office on 16, Berkeley Street in London, however, the reaction to all the criticism is that it is primarily a “perception” problem. As a result, Agarwal and his generals have set out to correct the perception with a counter public relations strategy.

The stakes are getting higher every day. Agarwal still needs an approval from the environment ministry without which his bauxite project would be stalled. A multi-billion dollar fund-raising exercise is on the way. Word is out that a few more investors could pull out of Vedanta, though this remains purely speculative as of now. But more importantly, bad reputation could come in the way of Agarwal’s dream to make Vedanta one of the top five mining companies in the world.