How Kalanithi Maran lost SpiceJet

Ajay Singh and yet another set of investors try their luck at turning around an airline with an amazing history

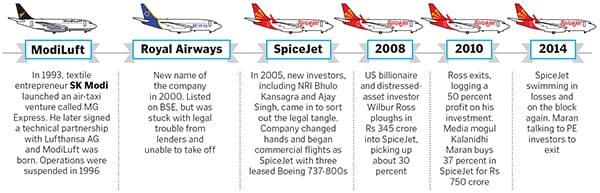

Changing hands one more time, SpiceJet has earned a place in Indian corporate history. Though the story is still being scripted, the first few chapters could well prompt best-selling business fiction. In the 21 years since it flew in its first avatar, ModiLuft, four sets of promoters have brought in fresh capital and new ideas- each trying and make a success of it.

The biggest of the bets was taken in June 2010, when Kalanithi Maran, chairman and managing director of the Sun Group, paid Rs 750 crore to buy a 38 percent stake in SpiceJet from American private equity investor Wilbur Ross and the UK-based Kansagra family. Over the last few years, he invested another Rs 800 crore, increasing his share in the company to 53 percent.

There is a sense of déjà vu about Ajay Singh, leading the revival this time around. Using his network in the financial world, Singh was able to bring in successive rounds of funding between 2002 and 2010 (when Maran came in). During these years, half a dozen FIIs and FIs, including IL&FS and the Tatas, bought into and exited SpiceJet. Significant among these was Wilbur Ross, who is famous as a ‘vulture investor’, specialising in funding distressed assets. Ross bought out Ajay Singh and, partly, the Kansagras, and exited at a profit in 2010.

SpiceJet’s unravelling is possibly the unkindest cut for Maran. When he bought into it, India was already littered with examples of airlines that were either dead or dying (Kingfisher had begun drowning in debt; Air Deccan, MDLR and Paramount had faltered too). Members of the staff who were present in the office just after his company Kal Airways, that part of the Sun Group that manages the airline business, took over in 2010, say he was brimming with confidence. In one informal address, he said the days of instability were over and this was the last time the airline was changing hands. “Maran had drunk the kool-aid,” says a New York-based aircraft lessor, who has done business with the billionaire. And Maran believed he could make it work.

Not the one to waffle, he made swift changes. Within a few months, he ordered 15 smaller aircraft, Bombardier Q400, worth $450 million to service smaller cities. The aircraft flew higher and faster than the French-made ATRs that rivals like Jet Airways and Kingfisher Airlines had been using. Maran also ensured that the planes were delivered within one year. SpiceJet’s fleet zoomed from 22 planes to 51 in one year. The number of flights grew by 111 percent in that period (between October 2011 and December 2012) and the market share improved. By December 2012, SpiceJet controlled about 18.5 percent of the domestic skies. Maran also brought in a new CEO, Neil Mills, to run it in the classic LCC (low-cost carrier) mode.

Devil is in the detail

Over the last decade, India’s airline industry has gained disrepute in the global aviation community for being weighed down by chronic oversupply and high costs. “The problems are fundamental and not cyclical,” say HSBC analysts Rajani Khetan and Mark Webb in a report titled ‘Indian Aviation—Don’t Expect a Reversal of Misfortunes’. Costs are high relative to pricing power, the report says, and the deterioration is likely to continue with two new players, AirAsia India and Tata-SIA.

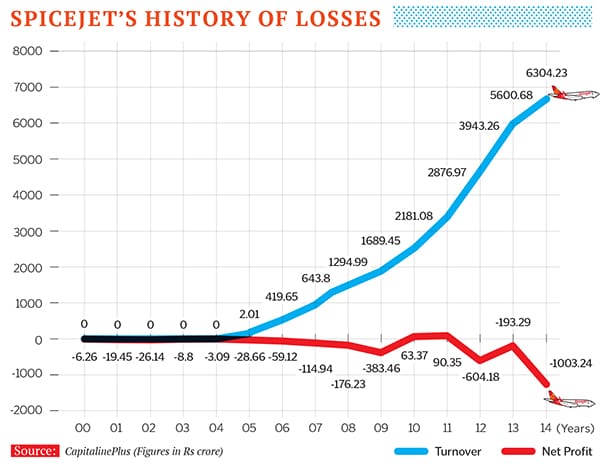

Maran tried to buck the trend. To be fair, for a brief while, his magic seemed to be working. After 10 years of losses, the airline made profits in 2010 and 2011 just as he settled into the new business. But deep within, things were not okay. Insiders say the management had little understanding of the airline business. “SpiceJet was being run on a cash-basis. Accrued expenses were not taken into account, and provisions were not made,” says a consultant who has worked closely with the airline.

Short-sighted steps were taken while negotiating contracts, especially for the maintenance of aircraft and engines. “Engine contracts had high number of exclusions, and this cost the airline an arm and a leg when there was a snag,” says a senior company source. Smart airlines the world over ensure iron-clad maintenance and power-by-the-hour parts and support contracts for engines. Even if they are a little more expensive, these contracts put the onus of maintenance on the manufacturers (CFM International for SpiceJet’s Boeing 737s and Pratt & Whitney for the Q400s) to make certain that the engine is serviceable.

SpiceJet got hit with huge maintenance bills, often paying 30 to 40 percent more. The Q400s were being sent to Samco Aircraft Maintenance, an MRO (maintenance, repair and overhaul) service provider in The Netherlands, for major checks, and at a very high cost. This was later changed; maintenance is now being carried out in India.

The other issue was the low utilisation of the new planes. The idea behind adding so much capacity, and so fast, was to be able to fly the Q400s for at least 11 hours a day and improve cash inflows. But ground realities—turnaround times at airports were higher than expected, permissions took time—were different.

By the end of 2013, both the revenue and cost sides of the airline’s operations were completely off-kilter.

“When revenues are not in line with costs, the only thing to do is to slow down and take stock,” says Dinesh Keskar, Boeing’s senior vice president of sales for Asia-Pacific and India. “Running an airline based on forward cash-flows is not the smartest thing to do,” he says, referring to the bargain-fare sales that the airline was becoming famous for.

One person who is unapologetic about SpiceJet’s low-cost strategy is Sanjiv Kapoor, the airline’s chief operating officer. After all, he had been hired to do just that.

By mid-2013, SpiceJet was making losses even in peak season. Neil Mills was shown the door, and a new team took charge. Kapoor was brought into SpiceJet to try a new approach.

But the discounted fare sales are being highlighted as the reason for the airline’s failure. And Kapoor has been strongly defending them. For instance, this Christmas, he tweeted a link to an investor presentation on the SpiceJet website, saying, “This should be a “must read” for all those who write cluelessly about “fire sales” without understanding a thing about revenue management.” For all his clarifications, most people still tend to link low-fare offers with airlines in distress.

Maran refused to speak to us but in a lengthy conversation with Forbes India, Kapoor said that from January 2014, SpiceJet has been following the classic LCC strategy of stimulating demand and this had helped improve revenues. “We were building loads through advance purchase fares (30 days or more) and promotions. This helped us generate revenue for what would otherwise be excess capacity or empty seats and command better prices on tickets booked closer to the travel date (15 days and 7 days),” he says. “In the last quarter, our revenues went up at twice the rate of capacity increase. Our losses decreased 57 percent year-on-year. This would not happen if the pricing strategy was a failure.”

Sun Group chief financial officer SL Narayanan says they ran out of time because of previous losses and delays in planned funding. Kapoor admits that SpiceJet has lagged in keeping costs in control. “Some contracts need to be re-negotiated, but we are not in a position to do that right now,” he says.

Not surprising, that.

Dues to vendors, including lessors of aircraft and maintenance companies, were Rs 742 crore on December 10, 2014. An ICICI Securities report estimates SpiceJet’s total outstanding to be Rs 2,000 crore. And at this point, vendors are unwilling to do anything till they are paid. Leasing companies have begun taking back their planes after the airline delayed payments and diverted funds towards paying service tax and TDS arrears that had built up starting early 2013.

“The plan was to defer payments to increase working capital, and pay them later with interest,” says Kapoor. Of the 37 Boeings that the airline had in July 2014, about 16 have been re-possessed by lessors. Some are grounded for lack of spares.

Kapoor says Maran has allowed professionals to run the airline independently. But unwilling to pump in any more cash, the entrepreneur has now cut SpiceJet loose.

Maran owns about 75 percent of (listed company) Sun TV Network, which had revenues of Rs 2,097 crore and a profit of Rs 717 crore in 2013-14. He could, technically, have sold a part of this to fund the airline. But unlike Vijay Mallya, he seems to have decided to stop throwing good money after bad.

Political Headwinds

Truth is, Maran is no longer on as firm a footing as he was in 2010, when he bought into SpiceJet. In September 2014, the CBI began proceedings against his brother Dayanidhi Maran. According to the CBI, Dayanidhi—who was telecom minister at the time—had “pressurised” and “forced” Chennai-based telecom promoter C Sivasankaran to sell his stakes in Aircel and two subsidiary firms to Malaysian firm Maxis Group in 2006.

The Malaysian firm was allegedly favoured by Dayanidhi and granted licence within six months after the takeover of Aircel. The firm then invested in Sun Group’s DTH business, Sun Direct, which was also named by the CBI in the charge sheet.

This, airline sources say, scared away one PE firm that Maran had exclusive negotiations with. “We expected to close a deal with a private equity player in the first half of 2014, but this did not happen,’’ says Kapoor.

Is there a silver lining?

Yes, believes Keskar. He is hopeful that falling fuel prices will help cut costs and make it attractive for the new investors. The airline also has 42 Boeing 737 Max airplanes on order. These are the newest generation of 737s that will hit the market in 2017, and SpiceJet’s deliveries are scheduled for 2018. From a potential investor’s point of view, these slots could be of value.

SpiceJet still has many things going for it and its 5,000 employees have their fingers crossed.

The entire Bombardier Q400 fleet is owned by the company (not leased), and this will be counted. So will its existing network, offices as well as landing and parking slots at various airports. The big difference between now and the past is that government policy allows up to 49 percent FDI by a foreign airline. This provides an exit route for financial investors, who could move out, making way for a strategic investor.

Restructuring, inevitably, will be painful. But in SpiceJet’s case, it is just one more chapter of a great entrepreneurial story.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)