How Chandra Helped TCS Climb To The Top

Under N. Chandrasekaran’s watch, the company is more visible, more aggressive. The challenge now is to make sure it remains out of rivals’ crosshairs

It was December of 2005 and the Galapagos Islands were teeming with the plants and animal forms that had caught the attention of Charles Darwin more than 100 years ago. Darwin’s study of the island’s finches, among other things, helped him devise the theory of natural selection: Species that adapt to their environment have a better chance of survival. It was perhaps natural that S. Ramadorai, then CEO of Tata Consulting Services, the oldest company of the Indian IT industry, selected Galapagos Islands for a tour of learning and therefore pleasure. He discussed this with N.

Chandrasekaran, popularly known as Chandra, and Gabriel Rozman, TCS’ Latin America head. They agreed. They were anyway in Ecuador to look at the possibility of opening an office there.

“Ram was fascinated with things on the island,” says Rozman. There was so much to see! The Galapagos penguins, green turtles, iguanas, cormorants, Nazca boobies and, of course, three varieties of Darwin’s finches. Ramadorai wanted to soak it all in. “After the third day, Chandra came up to me and said ‘I have seen what I wanted. Let’s go back to Ecuador’,” says Rozman. They flew back and over the next two days, they worked out a detailed plan to increase the business from Latin America. The results are beginning to show now. TCS is poised to make $1 billion a year in revenue from its Latin American operations. In Rozman, Chandra has also found his next delivery network head, the first non-Indian to play that role.

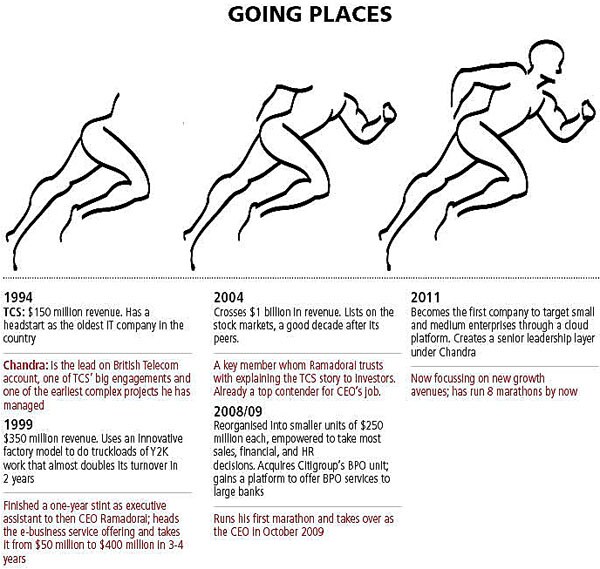

For Chandra, who succeeded Ramadorai as CEO in October 2009, Darwin isn’t just about a theory. He is busy making TCS adapt to the new demanding world of IT services, where if you don’t adapt, you vanish. And Chandra is passing on this message in his quiet, yet firm way to the entire company.

TCS House, the headquarters of the $8-billion IT giant, is an unlikely IT office. It isn’t a symphony of steel and glass like the offices of its peers Infosys or Wipro. The sandstone concerto, located in South Mumbai, is just four floors and offers some grand views from an older time. The best one is of the building across the road: The Deutsche Bank building. That’s where Ratan Tata grew up. The Tatas had to sell it in the Nineties. Today, TCS, the crown jewel of the Tata group, has over $2 billion in cash but the building isn’t on sale.

Chandra, the man in charge of Tata group’s cash machine, isn’t in the office. He rarely is. He travels 20-23 days in a month, meeting customers in different corners of the world and employees at various TCS campuses.

On this particular day, he is in Bangalore pushing the envelope on his other passion: Long distance running. TCS is sponsoring the 10K run in the city and because ITC is a hospitality partner, there is the unlikely combination of a senior Tata group official in an ITC hotel. When he steps into a deserted part of the lounge to meet with Forbes India, he looks a little weary and a shade older than 46. His gaze is remote. In the course of the next 60 seconds he finds his voice and his rhythm.

“It is okay to fail but you must push yourself. And you have to look at scale. Small improvements are fine, but you must go for things that will make a big impact,” he says.

He has lived those words. Since the time he has taken over, revenues have increased from $6 billion to $8.2 billion. The market value of the firm has doubled. Margins have improved. In the last one year, TCS stock has bettered all its peers listed in India — Infosys, Wipro and HCL.

The biggest shift though is in the way the industry, analysts and media now perceive TCS. Till now TCS, though big, was stodgy. Infosys was the cool one whose campus was on the itinerary of visiting heads of state. Infosys pretty much set the tone for the entire industry. But now it is TCS that is being taken as a yardstick of how the industry is performing. Part of it has to do with Chandra’s charisma and performance. There is now a hugely saleable face to TCS. The other factor is timing. Chandra’s ascent has come at a time when his rivals are a weakened lot. Infosys, with its fearsome combination of N.R. Narayana Murthy and Nandan Nilekani, was formidable competition as was Wipro during Vivek Paul’s time. Today that charisma is all Chandra’s.

Chandra has taken all the elements that the company’s previous CEO S. Ramadorai built over his 13-year stint, and infused it with energy. Ramadorai built TCS with a steel frame of solid engineer-managers like S. Mahalingam (the CFO), S. Padmanabhan (now with Tata Power) and of course, Chandra. Over time the size of the steel frame grew, but so did the bureaucracy. “When I joined, I found the administration and procedures very stifling. It resembled a government organisation,” says a TCS vice-president who joined the company six years ago. When Chandra took over, he devolved decision-making down the line and improved IT systems so that inefficiencies could be spotted. The company is now lighter on its feet.

Ramadorai led TCS, for most part of his tenure, away from the cacophony of the stock markets. TCS listed only in 2004, while all its peers listed at least a decade earlier. The culture at TCS is therefore to take a slightly longer view. The best example is its projects in India: It had a hand in the India business even when the India business wasn’t big.

“Ten years ago, you would hear of TCS writing a software program for the forest department in Kerala! We used to think ‘they must be nuts’,” says a senior executive in a company that will challenge TCS in the near future. In those days, the returns from Indian markets were peanuts in comparison to Western markets.

Chandra has kept that long view alive. For instance, he has got TCS to scale up its India business and build out profitable businesses in telecom, banking and even enterprise automation. The India business doesn’t have the same profitability as the US businesses, but that hasn’t deterred TCS. “What I like about TCS is that they don’t play to the gallery from stock market perspective. If they believe in something, they go ahead and do it,” says a former Wipro senior executive.

This makes Chandra even more important for the company. He is the last link between the past of F.C. Kohli and S. Ramadorai, and the future of TCS. His job is as much about retaining the traits that made TCS, as it is about adding new desirable characteristics.

Why does TCS, the largest Indian IT company, need Chandra to change its agenda? It is precisely because the going is good. The global IT services demand is changing in nature. Customers want companies like TCS to take more complex work. Its global competitors IBM, Accenture et al are scaling up fast in India. Its peers like Infosys and Wipro have new CEOs at the helm and they would be dying to put the champion to test. HCL Technologies and Cognizant are on a roll. “You should change before you are forced to. It is not a pleasant feeling if you are forced to,” says Chandra. He is the man to prepare TCS for the next phase because it is hard to tell when he can step up the pressure.

Chandra was the first masters in computer applications (MCA) to be hired by TCS. MCA was considered a poor cousin to a formal engineering degree those days. “The person who hired me said ‘you are the test case. If you do well then we will hire more MCAs’,” says Chandra with a chuckle. He did not let the pedigree bother him. “Many of us felt bad that we were doing BSc, and not BE. We felt we were second class citizens but not Chandra. That didn’t seem to bother him at all. He went about as if this was exactly what he wanted to do,” says M. Udayshankar, Chandra’s classmate, who is now a businessman.

And he possessed stealth even then. Not a single professor of REC Trichy, from where Chandra completed his MCA, is able to recall him. Two of his classmates try and jog the professors’ memory, but in vain.

“Chandra will remember every single one of them. I can assure you of that,” says Ravi Viswanathan, a TCS old-timer, head of the telecom business and one of the eight people who are now his direct reports. That’s the thing about Chandra. He doesn’t forget.

When Viswanathan was new in TCS, he was in charge of a team that bid for a project in Scandinavia. The project was small for TCS, with about $100,000 annual revenues. “It had the potential to go up to $250,000 if we performed well. But the contract was complicated. The penalties were stiff if we didn’t meet targets,” he says. Somebody advised Viswanathan to call Chandra. By then Chandra was already known as the “big projects” guy in TCS. Viswanathan tracked him down in the UK. “When I called him and told him about the deal and the terms, he told me to sign the contract. He said the contract could scale up to at least $1.5 million,” says Viswanathan. The next morning Chandra called up Viswanathan and gave the name of a person. “He said ‘talk to Kalpana. She has worked on such a project in the US and I will make sure that she is available for your project real soon’,” says Viswanathan. Eleven months after the contract began, TCS was able to make $3 million from the engagement.

Stories like this can be heard from almost every senior TCS staffer. Chandra, it would seem, was the human database for the company. He was managing important technical knowledge and a talent inventory all inside his head. That might give the impression that he is superhuman. Nothing could be further from truth. He is only too human.

In September 2007, Chandra and Venguswamy Ramaswamy, who was then heading the small and medium business initiative in TCS, had a problem. They were both diabetics. Ramaswamy had learned to live with it. Chandra had some other thoughts. “He said this is very bad. We must reverse diabetes,” says Ramaswamy. Ramaswamy nodded his head. “I thought this will go away,” he says. Chandra then proposed that they should take up running.

“Chandra said let’s go for a run at 4.30 in the morning. I told him ‘That early? Dogs will chase!’” says Ramaswamy. He reached Chandra’s house in Worli, Mumbai at 5 a.m. “We ran the first kilometre. The next we walked. I thought to myself ‘this is insane’,” he says. More insanity was to follow. Chandra decided that he would run the Mumbai marathon in January of 2008. “I thought it was going out of control but I kept my cool and suggested ‘Yes, Chandra they have a dream run. We will try for that’,” says Ramaswamy. Chandra was adamant that he would go for the 42-kilometre full marathon. Now Ramaswamy was really concerned. Chandra travels a lot. How will he train? Perhaps that will take this crazy idea out of his head, he thought. But Chandra started playing mind games!

“Every morning, I and others in the company, who also took to running, would get an SMS from him describing how he had run 5 kilometres; 7 kilometres; 12 kilometres. That made all of us very nervous. He was TRAINING!” recalls Ramaswamy. The group had no choice but to become serious about running. Then the group put pressure on Chandra and sent him SMSes describing how they had run 12 kilometres; 16 kilometres. “In December, we ran from Worli to NCPA [National Centre for the Performing Arts at Nariman Point] and back: 24 kilometres in 4.5 hours,” says Ramaswamy. Chandra ran the full Mumbai Marathon in January 2008. “Took me six hours but I had to finish it,” says Chandra.

Chandra wasn’t satisfied. He then signed up for training under Deepak Londhe, a distance running coach. “Come rain or shine. He would run at least 7 kilometres daily,” says Londhe. Since then Chandra has run six marathons around the world. It is also a great way for him to connect with the rest of the company. Now at least 2,000 people run regularly inside TCS and before every run, where Chandra is participating, he is seen talking shop with TCS employees. And sometimes even signing autographs and posing for pictures.

Something else happened in 2007. One day when Ramaswamy and others were running with Chandra, he said that TCS should look at small and medium businesses (SMBs). “I laughed and made some casual remarks about how TCS would lose its shirt and pants in servicing the small enterprises. I was quite happy doing consulting for US clients,” says Ramaswamy. Chandra did not respond then.

Six months later in February, the entire senior team was invited to a Chandra presentation. “He had outlined how he wanted to go after the SMB market. So I was trying to be helpful and kept giving suggestions right through,” says Ramaswamy. Soon after the presentation he was told the new SMB initiative would be headed by him. “Go figure it out he said!” says Ramaswamy.

Ramaswamy travelled across India meeting small and medium businessmen. The Tata logo helped. Nobody refused to meet him. And small businesses laid out their tale of woe to him. “One guy in Coimbatore told me, ‘First I upgrade the anti-virus. Then the PCs become slow. Then I have to upgrade Windows. And after that the local Mr. Fixit says I have low RAM. I know Lord Ram. What’s this Low Ram!’” he recalls.

TCS was onto an opportunity. Chandra was quite clear that the offering would have to be sold like electricity, as an on-demand service where you pay as you use, but the group didn’t know how they would do the billing. “Chandra suggested we look at one of the billing algorithms from the telecom domain because he thought the telecom companies are very good at billing for even a fraction of a second,” says Ramaswamy. Thus the iON platform came to fruition.

Clayton Christensen, a TCS board member and the guru of disruptions, says that in many other companies where he is a board member he keeps saying “let’s disrupt ourselves”, but to no avail. “This year I was battling illness, so decided to contribute from remote. And I said TCS must disrupt itself and look at serving the small and medium businesses. And Chandra said ‘We’ve already done that!’” he says.

iON already has 200 customers and if things go to plan, it should be a billion-dollar business in the near future. “With other companies where I am a board member, I do my homework so that I can contribute. With TCS, I sit in the meeting with a writing pad so that I can learn,” says Christensen.

On a different note, today Ramaswamy and Chandra don’t have to take any medication for diabetes. It has been reversed to the extent possible.

As Chandra has gotten more fit and agile since he took over as CEO, so has TCS. The secret of the company’s vitality is a combination of two things. The first step has been to divide the company into 60 small units, each of which have up to 3,000-5,000 people and revenue of $100 million to $150 million. For instance, the entire banking unit has been sub-divided into four smaller units.

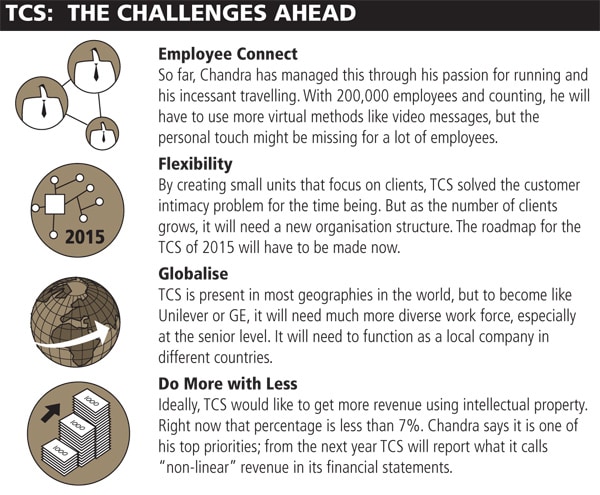

The second step has been to direct each of these units to deal with a set of clients. “When you come to our Chennai campus, even a junior-level person will say he is working [for] GE or Citi, not TCS. We have got them to think as if they are employees of the client but working at location in TCS,” says Ravi Viswanathan.

Now a client deals with one person at TCS, so there is less possibility of mixed messages. This person also has the advantage that he can see how much business he can get from the client. The best result of this move is that most decisions, including pricing (subject to a floor), can be taken at the level of these 80 units. “Units of this size allow people a lot of freedom to do things. They don’t have to check with me or Maha[lingam]. It gives them the feeling that they are in control. In turn, I hope they will deliver the results that are expected of them,” says Chandra.

Steve Morrison, head of Global IT outsourcing at GE, has been looking at offshore industry since 1995. He says that over the last few years TCS has gotten much better at customer centricity. GE is one of TCS’ top 10 clients and buys a whole range of services from TCS. “I don’t want to talk to a number of people to resolve my issues. This is where they are good —there is one relationship manager — Anupam — who is really my only contact. The mere fact that I no longer need to see Chandra very often should tell you about empowerment and customer centricity,” says Morrison.

For administrative purposes, these 60 units are grouped under 24 larger groups. This is to ensure that support functions like HR, payroll and transportation get a certain minimum size to deal with. Earlier, all the 23 heads of these groups used to report to Chandra directly but he has now put eight of his crack lieutenants to oversee them. Perhaps the next CEO of the company will emerge from this bunch. This is an excellent way to test their mettle. This way, Chandra gets more time to focus on growth areas, for example iON. Chandra will directly review only these eight. And Chandra’s reviews are tough, but also a source of growth for the company.

Growth is the source of energy. It gives you the ability to create jobs. For that to happen, you must not begin with excuses,” says Chandra. The annual planning meeting in September is where Chandra reviews his direct reports. Till last year, each of the 23 heads got 25 minutes each to present their plan for the year. And it is here that Chandra gets into details. “In these sessions I want to go beyond the aggregates. I must know which part of a person’s portfolio is growing at 40 percent and which is at 5 percent,” says Chandra. And he can be quite clinical when the 5 percent doesn’t start growing faster.

One of the 23 seniors recalls an incident. He had come in from Chennai for a meeting and was staying at the TCS guest house in Worli in Mumbai, which is close to Chandra’s house. Chandra offered him a drop. Both of them got talking in the car and after a while Chandra asked him about the business he was expecting from an Indian bank. “I told Chandra we will do $20 million and grow it at 15-20 percent,” says the business head. Chandra was aghast. He felt the bank could easily give double the business. “I said ‘Chandra that is difficult’. So he asked me ‘who has told you the business is worth $20 million?’ I said my account manager for the bank,” says the business head. Chandra told this person to change the account manager because he had become too comfortable. The business head wasn’t so sure.

“The next morning, Chandra called me and asked me if I had thought of someone! I had to get in a replacement quickly,” says the business head. The happy part of the story is that the account grew to a $51 million business in a few months. Chandra himself thinks that what he creates is “positive pressure”. “When you have the self-belief and there is an expectation from you, then that is positive. I am always very objective. I focus on the issue and I never challenge the self-respect of the person,” says Chandra.

But he isn’t always so matter of fact. Viswanathan talks about the time when he brought two of his senior managers from Chennai to Bangalore for a review with Chandra. The review was quite severe. The young managers were shaken. As they were leaving the room after the walloping, Chandra asked them if they were staying the night in Bangalore. No, they said, they would want to get back home quickly. “But you must,” Chandra insisted. “He asked me to make sure their tickets were rescheduled for the next morning,” says Viswanathan. He had arranged two tickets for them to see the Chennai Super Kings and Royal Challengers Bangalore tie in some really nice seats!

Jack Welch once said: “The higher a monkey climbs, the more you can see his ass.” It is when you are at the top that the threat to your position is the greatest. And Chandra has a large list of things on which he will need to work to make sure TCS remains out of rivals’ crosshairs.

The first is efficiency. Since Chandra took over, the company has managed to improve operational efficiencies, and the result reflects in its operating margins. But rivals say that TCS is still spread too thin. One indication of that is revenue per client.

Historically, Infosys has been the company with the highest revenue per client. Today it gets $10 million per client per quarter according to research agency Prabhudas Lilladher. In the last two years, TCS has managed to close that gap considerably. But rivals say that the numbers have improved mostly because of one client, Citibank, which is now at a $500 million run-rate. “Take away Citi and the numbers will not be so attractive,” says a senior industry professional. Selling more to the same client ensures lower selling, general and administrative expenses, better management of resources on the bench and better client servicing. But Chandra is not losing sleep over this.

The one thing that keeps him awake at night is the ever growing number of people needed to grow revenues. At 200,000 people, TCS is now one of India’s largest employers. Each year, the company adds more than 20,000 people to its rolls. Over time, managing this mass and maintaining emotional connect with the employees will start to weigh on the managers. If TCS has to become a $10 billion or $20 billion organisation, it needs to look at a different way to grow.

“Going forward, and looking back on our own journey, as we scaled from where they are [$8 billion] to $40 billion, I think the biggest challenge is to recognise the various inflection points and respond quickly to that. That requires tremendous amount of energy and non-linear growth will be one such inflection point. That is something they need to watch out for sure,” says Wim Elfrink, Chief Globalisation Officer, Cisco, a big TCS customer.

Finding that answer though may be very important to the company and industry. The IT landscape is changing rapidly, the clear demarcation between software, services and hardware is now blurred.

Hardware companies like Dell and HP, and even software giants like Oracle are invading the services business. Driven by disruptive technologies like cloud computing, pure play services companies could lose their premium position. TCS and Chandra must now find the answers to keep the model from becoming redundant.

"Today, I am just as confident giving a project to TCS or one of my other preferred suppliers as I would be to IBM and Accenture. Where they lack is demonstrating confidence to the client that they can take on the large projects that IBM and Accenture do,” says Morrison of GE.

"Today, I am just as confident giving a project to TCS or one of my other preferred suppliers as I would be to IBM and Accenture. Where they lack is demonstrating confidence to the client that they can take on the large projects that IBM and Accenture do,” says Morrison of GE.

In 2008, TCS won a project from the Ministry of External Affairs to automate passports. TCS is paid a combination of project fee and an outcome fee based on the number of applications it processes. For the first time, TCS will be directly involved in setting up of 77 passport seva kendras (service centres) across the country.

It means handling the software and hardware, training of government officials as well as finding and fitting real estate space for the kendras. It’s the kind of business that IBM would pick up and deliver. But for TCS, the project was plagued with problems from the start and there have been frequent delays.

Now of course, Chandra has two people monitoring the project on a full time basis, but clearly he would want TCS to become better at such assignments.

Once that happens, he can take that special vacation that he wishes for. During this vacation, no one from the company will be expected to call him. Then he would have truly made TCS an industrial-strength world class company.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)