Franklin Templeton's Sivasubramanian KN: The Intelligent Investor

Superstar fund manager Sivasubramanian KN has helped one of India’s oldest fund houses give consistent returns. Now, he wants the next line of fund managers to take over

2:15 p.m. Chennai. There is no light on the first floor of Century Center at Alwarpet as the city, like the rest of Tamil Nadu, suffers from frequent outages. But most people inside the Franklin Templeton mutual fund office don’t bother to move from their cubicles. They form silhouettes in the glow of their laptops and there is hardly any conversation. They continue to work. Considering that Uttar Pradesh has just declared its election results and the stock market is almost in a tizzy, the mood inside one of India’s largest fund houses is surprisingly serene.

Sivasubramanian KN, chief investment officer-equity, sits quietly in a small conference room blessed by the afternoon Chennai sun. Like his team, he is nonchalant about the power situation in his office and in Uttar Pradesh. He doesn’t have any electronic device around him to keep a tab on the markets and doesn’t seem to be bothered about the way the Sensex was behaving that day. “Working in Chennai allows us to cut the noise and concentrate on our work,” he says softly.

Sivasubramanian spends most of his time trying to spot companies that will make profits over the long term and also fit in his overall portfolio.

Something he’s been doing with aplomb for nearly two decades. The Rs 4650-crore Bluechip fund that Sivasubramanian managed is the oldest private sector mutual fund scheme in the country—it was floated in 1993—and has consistently outperformed the market.

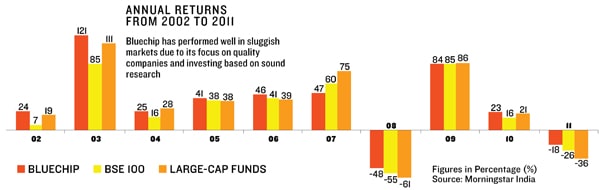

In the past 15 years, Bluechip has given a return of 22 percent, compared with a category average of 16. According to Morningstar India, it has a very high alpha (or excess returns against the benchmark index) at 6.89 percent. Most of its peers hover around the 3 percent mark. So, if you had invested Rs 10,000 in the Bluechip fund in March 2002, your money would have grown to Rs 93,000 now, against a category average of Rs 57,000.

But what makes Sivasubramanian stand out is not just the stellar performance of the Bluechip fund but also the way he imbibed Franklin Templeton investment philosophy—one that’s based on sound logic and intensive research rather than individual brilliance. In other words, he’s trying to become irrelevant. This is a marked shift from the prevalent culture in the Indian mutual fund space where top fund managers create an aura around themselves and try to become indispensable. “He takes his craft very seriously, but doesn’t take himself seriously as a fund manager,” says Pramod Kumar, CEO of Wealth Advisors India, a Chennai-based independent investment advisory firm and a former colleague of Sivasubramanian.

The Philosophy of Investment

Franklin Templeton’s investment philosophy helped the firm’s funds in two ways. One, it encouraged lead managers to identify the next level of leaders at the fund house. The strong focus on research allowed analysts to become co-fund managers and learn the ropes of successfully managing a portfolio early on in their careers. Already, Anand Radhakrishnan, who was earlier the head of research, has taken over Bluechip and is managing it successfully since 2008. “The system is based on merit. Senior colleagues ensure that their knowledge is passed on and there is always a hand-holding that takes place so that juniors don’t have to reinvent the wheel,” says Radhakrishnan.

Two, it helped Franklin Templeton weather the 2008 global economic crisis much better than most other funds which were seduced into investing in sectors that looked hot, but were not fundamentally sound. “We believe that research is more important than portfolio management. We want to develop research as a distinct platform for analysts,” says Sivasubramanian.

The years since the crisis have been brutal for mutual funds to say the least with the European debt crisis, Japanese earthquake and political instability further weakening sentiment. The Sensex (the Bombay Stock Exchange’s benchmark index) has been brooding around the 17,000 mark and struggled to break the shackles. For most equity funds it has been a tough time as there is no momentum and there are no favourite sectors. The number of funds outperforming the index has been dwindling and almost 53 percent of the funds have fared poorly for the last three years. But even in such conditions, Franklin Templeton is one of the few funds that has managed to ride the tide and maintain its high performance regardless of the state of the markets. Again, this has been possible because of the strong focus on research and having analysts with complete knowledge of their sectors as co-fund managers.

The idea of having research analysts as co-fund managers was not a brainwave or something that Franklin Templeton followed right from the beginning in India. It was something that Sivasubramanian and his equally-distinguished colleague Sukumar Rajah stumbled upon when the Flexicap scheme was launched in 2005 and collected around Rs 2000 crore in its new offer. Rajah and Sivasubramanian decided to take a stab at jointly managing the fund. The experiment was a brilliant success as it brought in a second, and possibly different, perspective on all decisions. More than anything else, succession planning was now easier as research analysts were exposed to portfolio management at an early stage.

All this has gone a long way in making Franklin Templeton, the only profit-making, foreign-owned asset management company (AMC) in India. So, how did this foreign fund survive in India when others have failed?

Acquisition And its After-Effects

The answer to that probably lies in the way it went about its acquisition of Pioneer ITI (Kothari Pioneer Mutual Fund). Though Franklin Templeton has been in India since 1996, it took over the assets of Pioneer ITI only in 2002. When it did so, it retained not just the employees, but also the distribution network of independent financial advisors that Pioneer ITI had assiduously built over the years. Franklin Templeton, in its earlier avatar, had been like most other foreign players—its schemes were sold through banks.

Besides Bluechip and Prima—the main schemes—Pioneer ITI gave Franklin Templeton two other valuable assets: Rajah and Sivasubramanian, two experienced fund managers known for their knack of picking winners under the leadership of Ravi Mehrotra.

“When you are acquiring something which you think is valuable to you, it is important that you give the investment team total independence. This has been Franklin Templeton’s approach across the globe and the investment team continued to function the way they used to earlier,” says Harshendu Bindal, president, Franklin Templeton Investments-India. And that’s not all. The investment team was also allowed to operate out of Chennai, a move that helped retain the talent in the team as many of them preferred to work there.

One of the first decisions that the team took was to keep focussing on what it were really good at—investment research. “A researcher is better placed to take a call on individual companies compared to a portfolio manager as they [portfolio managers] have to look at too many companies,” says Sivasubramanian, who had himself begun his career at Pioneer ITI as a research analyst.

Currently, the fund has 10 research analysts and four fund managers, making Franklin Templeton’s equity investment team one of the biggest in the mutual fund industry. Five of the research analysts are co-fund managers.

It’s not that a research analyst’s job at Franklin Templeton is any different. Here too they have to create a model portfolio and give recommendations. But unlike most AMCs, they are paid on par with portfolio managers and the model portfolio they create is taken very seriously by the fund managers. Most other funds ignore the recommendations of their research teams and the portfolio managers are in total command.

“It is a place where research analysts get their skin in the game as portfolio managers very early in their career path. That doesn’t happen in other places,” says Anand Vasudevan who is head of research and also the co-fund manager of Flexicap and Bluechip.

In 2006, Radhakrishnan, the then head of research, was made the co-fund manager of Bluechip. In a year’s time he became the fund manager for Bluechip, taking over from Sivasubramanian who decided to play a passive role as co-fund manager. Radhakrishnan was handpicked for the job after he proved his mettle by bringing 10 hybrid funds of Franklin Templeton under one strategy.

By November 2010, Sivasubramanian was promoted as CIO and Rajah moved on to become the CIO for Franklin Asia equity.

Big Shoes to Fill

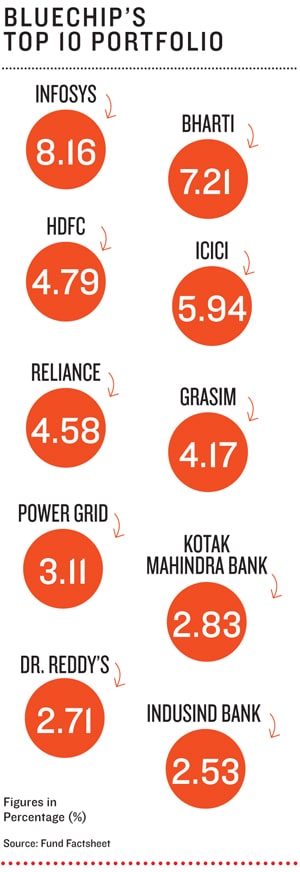

Sivasubramanian’s shoes were rather large for Radhakrishnan to fill when he took over Bluechip. But working closely with Sivasubramanian had taught him a few tricks. He realised that Sivasubramanian was a man of conviction. The moment he was convinced about a particular stock he put a lot of money into it. He maintained a concentrated portfolio and it was not unusual to see almost 7-8 percent of the funds invested into a single stock. “I think I’m conservative when it comes to portfolio management. I got to learn a lot from Sivasubramanian about how he goes on taking the concentrated bets,” says Radhakrishnan. Sivasubramanian himself is happy to play the mentor’s role and share the knowledge he has gained over the years with his team.

Like all others, it was in Mumbai that Sivasubramanian cut his teeth. Working with the project finance team at IDBI taught him the skill to dissect financial statements and understand the importance of a company’s ability to repay debt over the long term. He also learnt the significance of cash flows as well as the ability to study new emerging businesses. But there was one thing that he never quite learned or appreciated—the daily commute between Andheri and Nariman Point on a Mumbai local. So, when he heard about an opening with Kothari Pioneer in Chennai he was keen to take it.

He wanted to go back to his parents and the quiet of Chennai.

Within a year of him joining as a research analyst with Kothari Pioneer, he was promoted to manage Bluechip. Soon, in 1994, Sukumar Rajah too joined as a portfolio manager, and later took over as CIO-Franklin Equity from Ravi Mehrotra. Rajah had been advising the India Opportunities Fund, jointly managed by Indbank and Martin Currie, an international investment manager. He came into the Kothari team with a wealth of knowledge on emerging sectors. He was one of the earliest investors to take a bet on Infosys at the India Opportunities Fund. Before investing in Infosys, he had met the company’s management many times and also visited the company’s office.

Rajah believed that Infosys had a huge cost advantage over its US counterparts and started to invest in the company through the Prima Plus too. By 1997, Infosys became the top holding of Prima Plus.

Kothari Pioneer was the first fund to start an information technology fund in 1998. But when the sector began to show qualities of a bubble in 1999, it checked out. “We never sold out completely. We bought the sector much ahead of our peers and booked profits,” says Rajah.

HDFC Bank was another great pick of theirs. The stock was purchased when it was a midcap as both Sivasubramanian and Rajah believed that HDFC Bank had a great brand and would be able to raise deposits at competitive rates.

Sivasubramanian began to manage the Prima fund in 1997. In the same year they decided that Bluechip will concentrate on large-cap companies and Prima on small- and midcap ones. In many ways, it was more challenging for Sivasubramanian to manage the Prima fund as the portfolio needed more stocks to maintain diversification and ensure liquidity. “If we liked a particular stock we have never shied away from investing into it even if it was illiquid. We would only limit the overall exposure to the illiquid component of the portfolio,” says Sivasubramanian.

Sivasubramanian also learned to interact with a company’s management better and ask the right kind of questions. He started to focus on businesses that were using or deploying capital smartly and avoided conglomerates that were getting into areas that were not their core. “Good companies will not be available, cheap and poor management is always punished,” Sivasubramanian says.

In 2007, the Bluechip fund did not perform as well as some of its peers. But that was because Sivasubramanian and Rajah decided against investing in the real estate sector. They were not convinced by it. The fund grew 47 percent against 60 percent for the BSE 100 index that year. But 2008 and the global financial crisis proved them right. The Bluechip fund fell too (no sector escaped unscathed), but not as much as its peers.

“Bluechip is quite value-conscious and does not shy away from exiting momentum driven sectors, when valuations breach its comfort zone. On the flipside, it also doesn’t shy from taking contrarian calls from time to time. One example would be its overweight position in telecom in 2010, when others were shying away from that space,” says Dhruva Chatterji, senior research analyst at Morningstar India.

People who have worked with Sivasubramanian vouch that he never gets excited by volatile trends in the market. But for now, Sivasubramanian and Rajah have built a powerful fund house that functions like a well-oiled machine. For them, it’s not about success or whether they complement each other as a team. What they want to do is build strong processes that will last long after them. It sure looks like they are trying really hard to make themselves redundant.

Correction: This article has been updated with some changes made to the version printed in the magazine.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)