Fight or Flight for Indian Broking

These seem to be the only options left for a beleaguered Indian broking industry that is under attack from its technologically stronger global rivals

Other conditions being equal, if one force is hurled against another 10 times its size, the result will be the flight of the former,” says the ancient Chinese philosopher Sun Tzu in his classic military treatise The Art of War. This is as true on the battlefield as it is in the stock market, as many Indian brokers facing the brunt of bigger and technologically advanced rivals will likely agree. Confronted with contracting margins and declining profits, they are fighting the mother of all survival battles. A few have even shut shop.

Alchemy Shares and Stock Brokers is a case in point. For the 40-odd employees working in the firm owned by Alchemy Capital, June 27 began like any other day. They went about their business, took the usual coffee breaks and indulged in idle chat. But all that changed when Lashit Sanghvi, co-promoter of the firm, called the employees into his office and told them that he was shutting down their division. He gave them their June salary and a severance package. Sanghvi’s was not a rash decision. For a while he tried to get an international buyer, but when no deal materialised he knew it was closing time.

Nor is it an isolated case. In the same week, the promoter of another mid-size institutional broking firm asked its employees to take a 60 percent pay cut. This was unacceptable to the head of the division, who walked out with his entire team.

Over the past two months, many Indian brokers with institutional arms have tried to sell out to foreign brokers looking to set up shop in the country. In fact, a well-known investment banker is still looking for a buyer for three Indian brokerages and is in talks with some foreign brokerages.

Alchemy Capital was never a big firm but it wasn’t insignificant either. One of its promoters is billionaire investor Rakesh Jhunjhunwala. It’s only because Jhunjhunwala is a promoter that many investors bought the firm’s investment advice. Of course, all of this came to naught with Alchemy’s fight for survival.

For many, Alchemy’s fate is indicative of a deeper malaise in the Indian broking industry. Foreign brokerages with their superior technology and global presence are starting to get a choke-hold on their Indian rivals. If Indian broking houses were to write a research report on their own sector it would probably be titled ‘Sector Underweight’!

A major reason for their undoing lies in a little known formula that sits inside computers and helps in smoothening trade but is generally ignored by Indian brokers. It is known as Direct Market Access (DMA) and is slowly becoming the backbone technology for trades. Most Indian broking firms are just beginning to adapt to this technology, which is a precursor to algorithmic trading (see Forbes India September 20, 2010).

This technology has brought down commission revenues for brokers from 20 basis points to about 8 basis points in a single year. The effect on the finances of Indian brokers is visible. Over the past three years, revenues for listed Indian brokerages have fallen 3 percent, while profits have shrunk 26 percent. To make matters worse, expenses are rising sharply due to increasing salaries and technology investments.

“As in any other market, technology will be the biggest differentiator in the Indian market and it will be challenging for Indian brokers, who are relatively new to trading technology, to compete with the international players that have been in this business for a long time. In this scenario, Indian brokers will partner with foreign players and work like a sub-broker. At the same time, Indian brokers’ local expertise and knowledge will be valuable for the foreign partner,” says Murat Atamar, head of the Credit Suisse’s advanced execution services product for Asia Pacific. Switzerland-based Credit Suisse is one of the market leaders in institutional broking in India.

Statistics clearly show that consolidation is on its way. In 1999-2000, the top 100 brokers accounted for 49 percent of the total turnover on the NSE. In 2009-10, this rose to 73 percent and in the next 10 years, they are expected to account for 80 percent of the turnover. On the institutional side, which accounts for 30 percent of the total turnover, 10 brokers account for 80 percent of the trade. Almost all are foreigners.

Images: Vikas Khot

Big Fish, Fresh Prey (l-r) Morgan Stanley’s Parag Gude, IIFL’s R. Venkatraman and Motilal Oswal are all working out ways to adapt to the rapidly changing market dynamics

…Still the Foreigners are Coming

At a time when most Indian broking outfits are struggling to come to terms with a rapidly changing industry, at least three foreign brokers want to set up shop in India. Jefferies, a US-based securities and investment banking company; Barclays, which has a presence in India through consumer banking and corporate advisory, and Standard Chartered are some of the names that will enter the Indian market next year.

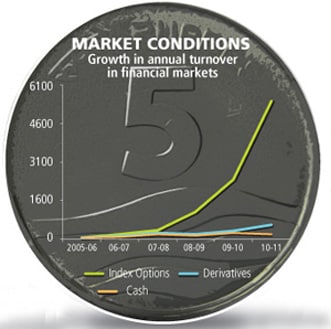

They feel that India and China are the only two markets that have the capacity to increase volumes dramatically in the long run. So every foreign player with an Asian presence wants to open its account in India. And why won’t it? Over the past five years the turnover in the cash market has gone up by an average 18 percent each year, while the derivatives markets have risen 43 percent.

Interestingly, even among the foreign broking firms, only Credit Suisse, Macquarie Securities, Morgan Stanley and CLSA have succeeded in the Indian markets. They account for almost 50 percent of the institutional market.

IIFL (India Infoline), Kotak Mahindra, Motilal Oswal, IDFC and Edelweiss are the major Indian broking firms. Though the global players have been dominating the sector in India for almost 10 years, there is palpable fear now among the Indians players that the foreign ones could raise

their game further and take over the entire market.

In fact, many saw the writing on the wall when industry veteran Vallabh Bhansali quietly sold off the investment banking, institutional broking and corporate advisory services of Enam to Axis Bank for Rs. 2,067 crore in November last year. Bhansali’s timing was perfect. Experts say that had the deal been postponed by even six months, he would have lost heavily on valuation.

Others are not as lucky. “If the market continues to be in the present state for one more year, then the broking industry will face difficulties. Only the top few brokers who have the balance sheet and ability to adapt to a continuously changing environment will survive. Challenging times will force the industry to consolidate in the future,” says R. Venkatraman, managing director of IIFL. In 2007, IIFL pulled off a coup by poaching Bharat Parajia and four of his colleagues from CLSA, a leading foreign broker, with fat bonuses worth Rs. 11 crore. But things have changed now.

The foreign brokerages want to hire fewer people and invest more in technology. Most of them have been working on their technology for almost a decade and have acquired a level of expertise that their Indian counterparts can now only dream of. So what is this technology that is so deadly to the health of Indian broking firms?

To DMA or Not to DMA

Currently, algorithmic trading that uses computers accounts for around 10 percent of the entire Indian market. This is much lower than the 70 percent for the US, Singapore and Hong Kong markets. More and more people are taking up Direct Market Access, or DMA, which allows institutional players to enter markets seamlessly without broker intervention.

US-based Progress Software is sure that technology will be the game changer in financial markets and is betting big on India. Giles Nelson, who is building the algorithm for Apama — one of Progress Software’s key products — believes technology can be the great leveler. If bigger firms are caught sleeping on innovations, the smaller ones can easily scale up if they have a smart algorithm. In the past year, Progress Software managed to get five clients, mostly propriety traders, in India. Globally, it has about 150 clients.

When it comes to technology, Indian markets are much more demanding than other Asian markets and require substantial investment. Most of the order flow is through one touch DMA, which is technologically more complex than straight DMA. This is not expected to change anytime soon. Also, there are very few institutions that have completely moved on to seamless DMA. Even those that have the technology use it only for 30 percent of the trades because the Indian markets are largely illiquid.

Another issue is that the gap between the bid and ask price in India is much smaller than other markets and the average size of a trade is smaller. This means what works in other markets will not work here.

Credit Suisse, the biggest player in the institutional business, has customised its technology for India. It has significant plans to expand its electronic trading here as it feels that there is high demand for technology.

But Parag Gude, a managing director at Morgan Stanley’s Institutional Equity Division, believes that technology is only part of the recipe for success. He feels that as domestic Indian asset managers grow, the opportunity for on-the-ground expertise will expand.

Morgan Stanley was the first to use DMA in the Indian markets two years ago and remains a dominant player in the space. “While electronic trading is well suited for the most liquid stocks in India, it takes local expertise to properly understand the nuances of the markets as you move down the liquidity curve,” Gude explains.

Options and Compulsions

There is evidence that Indian brokers are trying to move in to the derivatives side of the business to survive. Earlier, there was limited trading in the options market as investors found it easier to trade in futures. But now with advanced software and newer opportunities, most jobbers and day traders are operating in the options market.

A few other Indian brokerages are trying to cement their position in the customised investment advice space. They are creating advisory products that are not really PMS (portfolio management scheme) although they work like them.

Earlier, most of them sold their research to clients. But when mutual funds and portfolio managers began to hire their own analysts, Indian brokers realised the need to diversify.

Edelweiss is one of them. “Even if we are the biggest players in institutional broking amongst the Indian firms, you need to understand that only one-third of our business is associated with broking. We are an NBFC [non-banking financial company] with a presence in AMC [asset management company] as well as insurance business,” says Vikas Khemani, head of institutional equities, Edelweiss Capital.

Meanwhile, IIFL is focussing on wealth management and currently has assets under advisory of over Rs. 20,000 crore. It’s a new business for the company, and one it’s looking to dominate. Motilal Oswal is taking the innovation route. It has launched an ETF (exchange-traded fund) based on a foreign index, which it feels will give it an edge.

“We are a focussed financial services company building on mostly transaction-based and fee-based businesses. We feel that the Indian economy is going to grow at around 15 percent nominal growth rate and our growth target is at 25 percent for the next three years,” says Motilal Oswal, managing director of Motilal Oswal Securities.

Just seven years ago, it was possible to put up a full-fledged broking house with $1 million-$2 million. But today, it will require at least $10 million — the kind of money only a global player has. No market in the world has 2,000 brokers. Even the bigger markets have at the most about 100; the number will eventually come down in India too. Only the few who have deep pockets and the ability to adapt fast will survive.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)