DMart: The juggernaut continues to roll for India's value shop

DMart's methodical rise as India's top valued retailer has set it up for many years of rapid growth. And the juggernaut is being steered by Neville Noronha, the man hand-picked by media-shy founder Radhakishan Damani

(From left) Ramakant Baheti, chief financial officer, Neville Noronha, Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director, Dheeraj Kampani, Vice President, Buying and Merchandising, Uday Bhaskar, Chief Operating Officer, Retail, Narayanan Bhaskaran, Chief Operating Officer, Supply Chain Management

(From left) Ramakant Baheti, chief financial officer, Neville Noronha, Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director, Dheeraj Kampani, Vice President, Buying and Merchandising, Uday Bhaskar, Chief Operating Officer, Retail, Narayanan Bhaskaran, Chief Operating Officer, Supply Chain Management

Image: Mexy Xavier

Neville Noronha speaks with disarming candour. His answers, delivered cogently and with precision, are indicative of someone who has done his time in the trenches—in this case, on the shop floor—as well as in the corner office where he now plots strategy and figures out how the customer of tomorrow—and by extension, his business—will evolve.

No wonder he is the man to whom ace investor, the elusive Radhakishan Damani, has entrusted the task of steering the DMart juggernaut. And it is easy to appreciate why Noronha hasn’t let Damani, who started DMart in 2002 in Powai, down.

“I’ve learnt that big ideas don’t work,” the 42-year-old chief executive and managing director of Avenue Supermarts, which runs DMart, tells Forbes India. He, in fact, points out that they can actually work against you. “Instead, the wins in retail come from relentlessly pursuing small incremental improvements,” he says. Noronha even contrasts this with the “MNC culture” which focuses on the big idea and then does an average job of execution—he’s clear that this is not something that will work in Indian retailing. “You really need to love what you do day in and day out,” he says, adding self-deprecatingly, “if you’re too smart, the profession will bore you.”

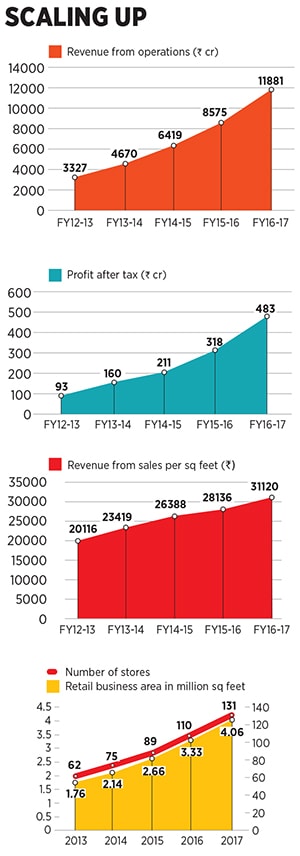

It is this philosophy that has made the retail chain more valuable than competitors Future Retail (₹25,000 crore), Aditya Birla Fashion (₹12,000 crore) and Trent Ltd (₹9,600 crore). DMart’s market cap, at ₹69,000 crore, is more than the combined market cap of these three. Since its listing on March 22, 2017, its stock price has soared by 260 percent to ₹1,110 from an offer price of ₹299.

But will the company be able to do justice to its lofty valuations? To understand that—if the DMart of tomorrow will grow and thrive —it is helpful to take a deep-dive into its past and track the story of a benevolent founder who carefully studied the business, trusted and nurtured a young management team, invested capital wisely and patiently, and finally shared the wealth he created with his employees.

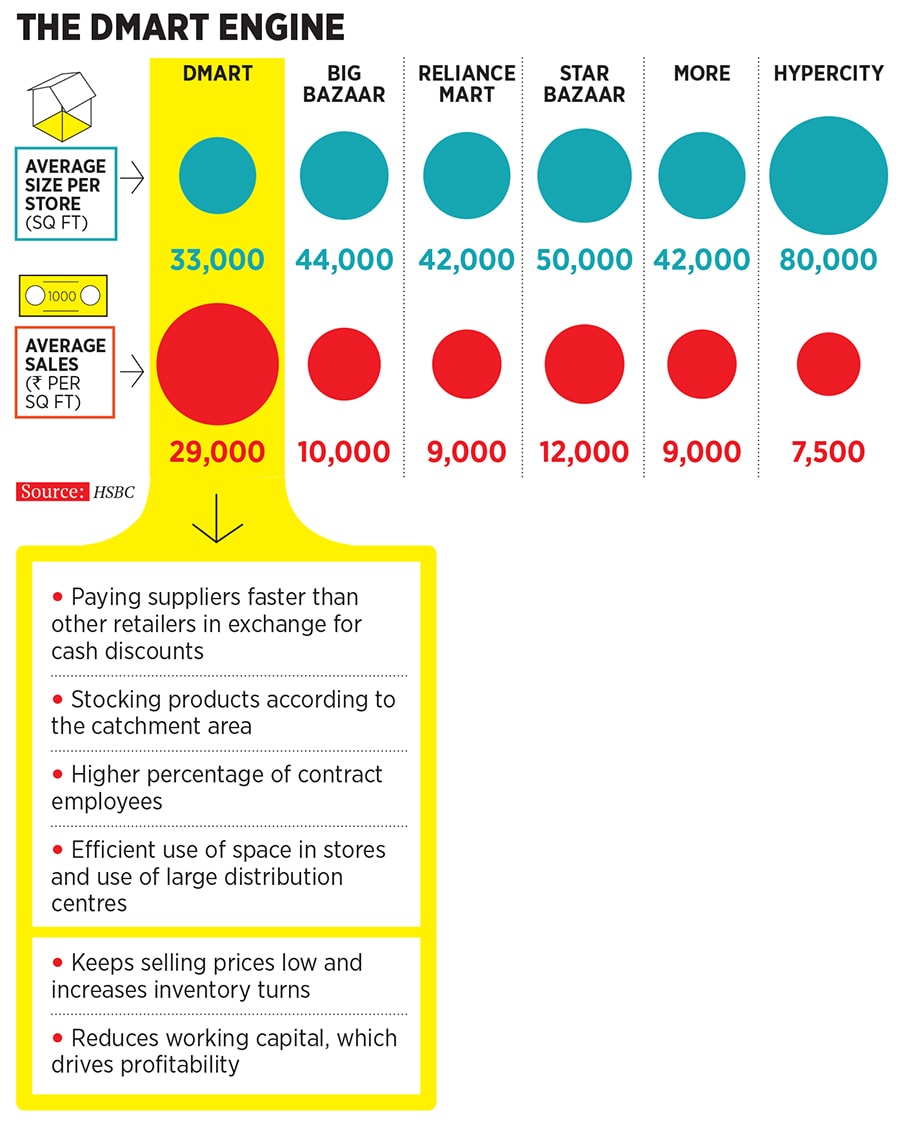

It also helps that DMart spent the better part of the last decade perfecting its business model. Unlike its rivals who, for the most part, focussed on achieving scale, DMart worked on keeping costs to a minimum and getting the per unit economics right. “Keeping costs in check has been key to its success,” says Rajeev Thakkar, chief investment officer at PPFAS Mutual Fund.

Take, for instance, racking. A company pre-IPO prospectus states that to effectively utilise resources, the company has higher racks—the upper ones used to store goods and the lower ones for display. Sounds intuitive, but few retailers take the racks all the way to the ceiling like DMart does. The result: More efficient storage of goods. Couple efficient operations with rapid expansion and the result is a company whose stock the market can’t get enough of.

The context is clear: India’s retail landscape is littered with businesses which either achieved scale at the cost of profitability (Walmart in India and the Future Group) or ventures that simply underestimated the challenge of running a retail business (More, Spencer, Easyday) and shut shop (Vishal Retail, sold and is now run by TPG). “Supermarkets, especially in the early days, struggled to come up with the right approach, a winning proposition and unit economics that could yield sustainable profits and be rapidly scaled up,” wrote HSBC in a June 2017 note.

The high mortality rate is a direct consequence of the peculiarities of the Indian market.

There is the maximum retail price, or MRP, regime. Goods in South Mumbai, where shop rentals can rival those in Manhattan or central London, have to be sold at the same price as, say, on the outskirts of Lucknow or Indore where the rentals would be a fraction. This places organised retailers at a big disadvantage compared to the kirana or mom-and-pop stores that run out of owned premises bought many years ago, with no rentals to pay. They typically have a far lower cost structure (they often use child labour or don’t have to pay employment taxes like provident fund).

Also, the famed inefficiencies in India’s supply chain are often not what they are made out to be. As Kishore Biyani who set up rival Future Retail has often said publicly, India’s traditional retail industry is very efficient, there is hardly any wastage of food, and the local kirana will deliver whenever you want, in the smallest possible quantity and offer credit.

This is a tough combination for an organised retailer with its high corporate overheads to beat.

So how did DMart do it?

Image: Mexy Xavier

Damani, 61, who typical of his media-shy reputation declined to be interviewed for this story, decided to try his hand at retailing in 1995. Ramakant Baheti, the chief financial officer of Avenue Supermarts and a Damani hand for the last two decades, says his boss entered the business “with a view to create something other than stocks to leave behind for the next generation”.

Damani, at the time, was a successful investor in consumer stocks—Gillette and VST Industries are two through which he made a small fortune. A believer in the power of brands, Damani, recalls Baheti, read up on global retailers before entering the business. While he was interested in the grocery side, he saw that, globally, value retailers like Carrefour and Walmart were the only ones to have achieved scale.

He earned his spurs over the next decade during which he ran two franchises for Apna Bazar. He’d spend time in the 7,000 square feet Nerul store and observe which items moved, how customers behaved and what level of discomfort they would put up with (unlike other retailers he eschewed air conditioning). But Damani had less flexibility than he would have liked as 60 percent of the assortment was dictated by Apna Bazar.

While those familiar with Damani were surprised at his choice of profession (retailing was looked down upon in the South Mumbai social circuit he was a part of), they were also impressed by his dedication. In 2000, Damani incorporated Avenue Supermarts and started a three-store operation named DMart two years later in Powai, and soon after in Kandivali and Malad.

Dheeraj Kampani, now vice president, buying and merchandising, at DMart, was then a sales supervisor with Hindustan Unilever and had interacted with Damani on several occasions. He recalls a man who wore only white shirts and trousers and sneakers and introduced himself as the purchase manager. “While he didn’t look like an employee, his mannerisms were not that of an owner either.” He also remembers Damani experimenting a lot while buying. The store assortment was his baby. He would say, “In retail, everything is science. Assortment is art.” Always on the lookout for a bargain, his line to Kampani was, “Price mera, quantity tumhara.” (“I state the price while you decide how much to supply.”)

Damani was actively involved in the business till 2006 and continued to mentor young merchandise buyers till 2011. Even today, he regularly talks to the team and visits suppliers in India and overseas. However, his only representation in the business is through his daughter, Mumbai-based Manjri Chandak, 32, who sits on the board as a non-executive director.

Noronha, who manages the business, had caught the investor’s eye and, in late 2003, Damani casually asked Kampani to have his boss (Noronha) call him. Noronha, who looked after modern trade accounts at Hindustan Unilever at the time, had by then moved to Delhi. In just eight years at the FMCG major, he had already made it to the management cadre—he had started as a supervisor in the market research department and then joined the sales team (also as a supervisor).

Damani wooed him over a series of conversations, but Noronha admits to being conflicted. Competition comprised players like the Future Group and RPG Retail with a larger scale of operations. But working at a smaller company was also an advantage, he thought: At the bigger retailers, he would barely get a meeting with the purchase manager, leave alone the CEO. At DMart, he would deal directly with Damani. More importantly, data revealed that DMart’s stores had the fastest throughput. Noronha’s only doubt was about the scalability of the model.

Nevertheless, Noronha signed on in January 2004 and started working at the Malad store as head of operations, where the entire DMart team operated out of “three desks”. And he started to make a difference from the get-go.

DMart’s strategy is in contrast to the Future Group’s which relies more on a loyalty-driven membership strategy where frequent shoppers are offered deals not available to others. (DMart has no loyalty programme.) To get the best prices for groceries DMart follows a simple strategy. It pays suppliers faster than others (on an average, 8 days as against 60 days by its rivals) in exchange for an upfront discount which is then passed on to the customer. Other savings are extracted through operational efficiencies. For instance, in 2006, when DMart was just a seven-store operation, it implemented its first enterprise resource planning (ERP) platform. “Over the years, we’ve implemented an auto replenishment system, which allows us to track in real time how goods are moving across any store in the network,” says Narayanan Bhaskaran, chief operating officer for supply chain management at DMart. By 2011, DMart set up a distribution centre. Unlike competition, it hadn’t spread itself thin across India; instead, it had clustered its stores across Maharashtra and Gujarat. Investments in an ERP platform and distribution centre allowed the company to have a far more efficient supply chain than competition, who did the same only when they achieved scale.

Squeezing costs was not just restricted to efficient buying and supply chain efficiencies. At the store level, Noronha and team took a careful look at every cost parameter. “They’d give buyers only as much discomfort as they could tolerate,” says a fund manager who has studied their model. (He declined to be named citing company policy.) The air conditioning was turned down, the aisles were not too widely spaced. Store employees were hired by an agency—“we later hired the better ones,” says Noronha —to cut costs and deal better with peak demand. DMart employs only half the number of employees per square feet as rivals, according to a research note by Ambit Capital.

The company also discounts products according to the catchment area. Shopping at the Powai store would be 5-7 percent more expensive than at the Chandivali one, according to the fund manager. The assortment also varies. DMart’s philosophy is to only sell items that have high turns. As Kampani explains, “We’d stock different soaps and detergents depending on what the catchment area of that store can afford.” The result at ₹29,000 sales per square feet is more than twice that of rivals.

All this results in a superior days sales of inventory—a key metric by which retailers are measured. DMart’s stands at 25 days, which compares favourably with Walmart’s 32 days for its global operations; Future Retail’s is 80 days.

DMart has also chosen to own the real estate on which its stores stand. In India, all other retailers rent; this allows them to expand faster and leave a location if the store does not perform according to expectations.

However, ownership gives DMart the latitude to get space at an attractive price at a new urban cluster, and allows for greater flexibility in store layout and the percentage mix of various products. But as it grows, sticking to the ownership model could slow down expansion. This is why it has also started taking stores on long leases.

At the same time, while buying property, Baheti says, the company is always cautious. He estimates that the total investment in the business (both in property and technology) has not been more than ₹500 crore to date and says Noronha and he have a competitive streak when it comes to sourcing the best locations. “We often joke with each other that the location I spotted is doing better than the ones you spotted,” says Baheti.

As modern retail drives deeper into India, DMart finds itself well-positioned to capture a large slice of the pie. The company has spent a long time perfecting its model—the first 10 years saw DMart scale up to 55 stores. It has since ramped up to 131 stores across seven states. As modern retail in India accounts for just 9 percent of the total retail industry, according to Technopak, there is immense scope to grow. The company says that any town with a population of more than 100,000 holds the potential for a DMart store. It will have to account for regional variations in the food palette, but is confident of getting it right.

In time, DMart also plans to work harder on its private labels as those will provide an additional margin kicker. “Brick and mortar retail is hardly a winner-takes-all business and there is enough space for several players,” says Noronha.

One area where DMart could face significant competition is ecommerce.

During the IPO roadshow, while investors were excited with how DMart had kept costs low, they were concerned about the potential threat from online retail. An aggressive move towards groceries by Amazon or BigBasket could have DMart on the backfoot. RedSeer Consulting estimates that there are 45 million online grocery transactions across India, which have far less widespread adoption as compared to, say, books, mobiles or clothes. Each customer shops about 10 times a year, making the online grocery shopping population 4.5 million strong. “Even in areas where there is direct competition, the online grocers haven’t been able to challenge the offline guys effectively as people want instant fulfilment, pricing and a wider range of products. As of now, online grocers are still struggling to get the unit economics right,” says Mrigank Gutgutia, ecommerce analyst at RedSeer Consulting.

However, an increase in smartphone penetration could change that. Noronha is cognisant of the threat, but has reservations on how soon and how large a threat it could turn out to be. Groceries occupy a large volume compared to other online purchase items, but are priced lower and have lesser margins. BigBasket and Grofers both lost money in the financial year ended March 2016, the last fiscal for which numbers are available. Sales at BigBasket jumped three-fold to ₹563 crore while losses rose four-fold to ₹277 crore.

This makes delivering profitably a challenge as customers expect a discount. “The biggest advantage we have is that customers come to our stores and take the items home themselves. Home deliveries are the fastest way to the graveyard,” says Noronha.

Hedging its bets, DMart is experimenting with a hybrid model —DMart Ready. These are small shops (no more than 200 square feet). Customers who have placed their orders online—they receive the same discounts as those who buy in-store—come and collect their items. So far, 40 DMart Ready stores have been set up. Home deliveries will only be offered for a fee.

For now, the DMart juggernaut continues to roll. “One has to realise that companies which succeed over long periods of time have robust systems and processes across functions. These ensure that they don’t stumble as they scale up or evolve. DMart fits that description,” says Rakshit Ranjan, portfolio manager at Ambit Capital’s Coffee Can PMS.

In the financial year ended March 2017, its revenues rose by 38.5 percent annually to ₹11,881 crore while profits increased by over 51.8 percent a year to ₹483 crore. The market expects it to continue to post quick growth. But there is always the question of whether too much growth has been priced in. At ₹69,000 crore market cap, the stock trades at an astronomical 121 times compared to the estimated March 2018 earnings. One reason for this could be the limited supply available—only 10 percent of the outstanding shares were divested during the March 2017 IPO.

In valuing a company like DMart there are other aspects that need to be considered—those that can’t be described in numbers. First, the extensive stock ownership plan that was rolled out across the company in 2009. In a series of conversations with Damani, Noronha convinced him about the benefits of the plan. Over 90 percent of DMart employees who joined the company prior to its listing in March 2017 have stock options. Noronha owns 2.44 percent while Baheti has a 0.57 percent stake. (As an aside, Noronha mentions he is extremely uncomfortable with the rising valuation as it puts additional pressure to perform. “The business drives us and not the valuation,” he says. In fact, Damani, who holds 82.2 percent, has shot up the annual Forbes India Rich List rankings to No 12 this year, with a net worth of $9.3 billion, which of course includes wealth from other sources.)

Second, the management team that DMart has built. Loyalty and long service are prized as is the ability to work in a team. In any organisation that grows rapidly, there is always a tendency for the early team members to feel left out. Noronha has strived to maintain a balance between the old and the new, saying that “fitting in” is a key criteria as is competence. There’s a convivial office environment and a superstar culture is discouraged. For the most part, the offices are open plan with a few see-through cabins.

As he looks back at what they’ve created, there’s a tinge of wistfulness in Norohna’s voice. Recalling his initial year at the Malad store, Noronha remembers how he and Kampani would joke that this job allows you to sleep well at night as you get so tired walking around the store all day.

He also mentions the first expansion outside of Mumbai into Ahmedabad where they fell flat on their faces. The store size had to be shrunk before buyers eventually flocked to the outlet. “That was a good reality check,” says Noronha.

And finally there is the stellar listing that has made Noronha’s stake worth over ₹1,600 crore and over 400 employees (mainly store staffers) worth over a crore each.

But some things never change. Noronha still drives his 10-year-old Skoda Laura and makes sure he visits stores often enough, interacting with buyers and staff alike. How the customer and the marketplace of tomorrow will evolve constantly keep him busy. “At the end of the day, we are just a product of the opportunity we got,” he says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)