Cisco's Second Place

Cisco’s efforts to set up another global headquarters in Bangalore hasn’t exactly gone to script

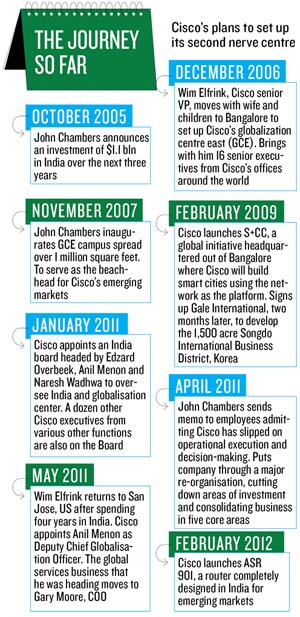

Five years ago, John Chambers, chairman and CEO, Cisco Systems, devised a bold emerging markets plan for Cisco, where the company would have two nerve centres: One headquartered in the West (San Jose, California) where the company began its life and went on to become the dominant networking company, and a second one in the East (Bangalore, India) where the future markets of the company lay.

He entrusted the task of setting up Cisco’s second global headquarters, called Globalisation Centre East (GCE), to 60-year-old Wim Elfrink, a Dutch, who is his friend and a key member of his leadership team. The GCE, with a campus spread over one million square feet, was unveiled in 2007.

The idea was that it would be a laboratory from where new products and business ideas would emerge.

Other global technology companies—IBM, GE, Microsoft, Intel—also had strategies to tackle the next frontier of growth, but none had sent a senior official like Elfrink to live on this side of the world, and no one had such a grand plan as Chambers’. Cisco has invested several hundred millions of dollars to make India a second global headquarters.

Now, nearly five years on, questions are being asked internally on what exactly has come out of these investments.

The backdrop to this is the fact that growth has stalled and profits have fallen. Last year was one of the worst in Cisco’s history, forcing Chambers to initiate a complete rehaul, cutting back investment in or exiting at least a dozen categories. With Chambers committed to cutting a billion dollars in expenditure this year, there is now greater scrutiny on every dollar that the company is spending. There are other pressures too. Chinese players like Huawei who have the advantage of low-cost R&D, have given Cisco a run for its money in markets like India and have now set up beachheads in the US.

Over the last few weeks, Forbes India spoke with Cisco executives across various levels, analysts, partners and industry experts, to understand if the centre in Bangalore had created an impact on Cisco’s performance.

The short answer: Not yet.

GCE’s outcomes have been incremental. In other words, what looked like a great idea on paper has been a very difficult thing to execute on the ground.

Chambers and Elfrink have a different view. “When you make revolutionary changes, people often ask why? They often doubt [it] but it takes four, five or six years before you see results,” says Chambers. “It’s an entirely different company from five years ago. I had a three-year plan. Looking at my goals, I will say I have met them all,” says Elfrink.

Some of the metrics bear that out. When Chambers and Elfrink visualised the globalisation centre, they talked about three axes—talent, innovation and growth. As promised, the number of people employed in India is expected to cross 10,000 this year, compared to just 1,700 when Elfrink first came to India in December 2006. Cisco was then operating out of leased buildings; it today has a state-of-the art campus in Bangalore. Cisco today has 14 VPs in India (it had just one in 2007) and over a 100 directors (from just eight). This makes up for 20 percent of the company’s top leadership, says Elfrink.

But a second global headquarters should mean that corporate leadership and functions are dispersed between the two centres. Yet, other than Elfrink (who returned to San Jose last year), none of Chambers’ other executive leaders have wanted to work out of Bangalore. While GCE has two senior leaders, Anil Menon and Faiyaz Shahpurwala, most corporate functions are still headed by people sitting in San Jose.

The roll out of new products—GCE’s raison d’être—has been extremely slow. The first made-in-India product has just gone on sale: The ASR 901, a low-power router targeted at telecom companies in emerging markets, launched in February.

Elfrink created a new global business, Smart+Connected Communities (S+CC), headquartered in Bangalore, where Cisco would aid cities in developing networking as the fourth utility along with water, waste and energy. Elfrink says S+CC has won eight iconic projects, including the $35 billion, 1,500 acre, International Business District in Songdo, South Korea, where a smart city is underway, and 50 smaller projects. In February, S+CC was selected by the Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC) to create the information and communication technology (ICT) master plan for two pilot cities in the $90 billion infrastructure project. But Elfrink says he cannot disclose how much revenue S+CC has generated, citing competitive reasons. “Two percent of all real estate development budgets go to ICT,” he says.

To be fair, globalisation has been tough for other companies as well. Pankaj Ghemawat, professor of global strategy at IESE Business School, and author of Redefining Global Strategy, says, “Cisco is an early mover on something that quite a few large companies are now trying in different ways. While the details vary, what is common is some degree of dissatisfaction with how sales are being built up, or other functions being performed in such markets.” The reason for that, he says, is that “if you are a large company with a large business in the West, those units are controlled by people who are focussed on those markets”.

Despite the challenges, Ghemawat says, globalisation is an imperative. “But this is one device that won’t solve the problem by itself,” he adds. The top management has to signal directly and indirectly that they are “watching to see how the organisation overall manages to achieve on this dimension.”

In early April, John Chambers flew down to Bangalore to do just that. On the last day of a gruelling six-day Asia tour, he met the top 80 leaders of the region in Bangalore. Also present were Elfrink and Edzard Overbeek, president, Asia Pacific and Japan. Chambers told them, “We have done the heavy lifting and investment and now you must make a difference to this company. Now we are at the point where we can really get big benefits from it.”

So, is he happy with the results coming out of Bangalore? “Anytime you try to do something different, whether it is an acquisition, or moving in a new market, the vast majority will disagree with you, but you have to have courage. I couldn’t be more pleased about making this our second headquarters. No one came to visit us here five years ago; now we have 50 customer visits a month, including heads of states and CEOs from major corporations around the world. Wim did a great job in making that happen,” he says.

In December 2006, Elfrink, who was then considered second only to Chambers in seniority, moved to Bangalore with his wife Kate and two young children as Cisco’s first globalisation officer. The media, both Indian and foreign, went into overdrive. Elfrink was the senior most person from an iconic technology company to move to this part of the world. He brought with him 16 executives from Cisco offices around the world.

It was a hard sell. The idea of the globalisation centre was radical and people working in San Jose were unsure about living in a developing country. Cisco went out of its way to make it easy for them, rewarding them handsomely. They were given a lavish lifestyle in a plush gated community in Bangalore.

The preferential treatment created severe heartburn. In San Jose their peers were jealous of the pampering; the locals in Bangalore were hurt because for the same designations they were being paid far less. In the beginning, the expats kept to themselves and largely socialised only with each other. A senior Cisco official says it was Elfrink’s wife Kate who first sensed the divide and after that there was a greater effort to mix the teams.

Elfrink’s own lifestyle came under heavy scrutiny. There was constant talk about how much Cisco was paying for renting Elfrink’s place in Bangalore (Rs 21 lakh per month).

Part of the problem was that there had never been a person of Elfrink’s stature living in India. “Here was a man earning $17 million a year. What is the big deal if he paid a rent of $40,000?” questions a Cisco India employee.

A lot of people didn’t understand that Elfrink’s house wasn’t just his residence; it was an opportunity for Cisco to showcase its products, says a senior Cisco director who worked closely with him. The house had every one of Cisco’s latest gadgets on display, including a TelePresence room, which was launched only a year ago.

“The Saudi royalty would come to his house and go back extremely impressed with what Cisco’s technology was capable of doing. If you look at it from that lens, the expense was justified,” says this official. Between 2008 and 2011, Elfrink hosted 800 chief executives at Bangalore. “Our Brazilian customers prefer coming here, because they want to see for themselves how our technology can work in extreme poverty and with frequent power outages. In San Jose, everything is so slick,” says Elfrink.

Chambers sent Elfrink to India because he was aware of Cisco’s command and control culture (he once told an interviewer that when he said right, 60,000 people turned right), and knew it would need someone of Elfrink’s stature to change things inside.

But Chambers and Elfrink underestimated the enormity of the task. The second headquarters was largely Chambers and Elfrink’s idea. Most people inside Cisco were sceptical. Says a senior Cisco official who no longer works there, “I had so many mental battles with my department head in San Jose. Every time I’d want to do something, there would be massive push back. It was exhausting.” In an interview to Forbes India in June last year, Elfrink said, “Globalisation needs not only top-level commitment but buy-ins from the entire organisation. If you ask me, did I have the right buy-ins in the organisation, I’d say, ‘No, I could have done better’”.

To make matters worse, just one year after the centre was inaugurated, the world economy suffered one of its worst recessions. Apart from globalisation, Chambers had opened up 30 other transitions, including a major push into consumer markets. The company was spread too thin. Chambers was under severe attack from analysts and shareholders and his attention was diverted in dousing fires at home. In April 2011, Chambers sent a memo to Cisco employees, admitting that the leadership had been slow in making decisions and that the company had slipped on operational execution. “We have lost some of the credibility that is foundational to Cisco’s success—and we must earn it back.”

Since writing that memo, Chambers has made some big changes. One of those is to decentralise decision-making. Beginning fiscal 2012, Cisco has organised its business into three geographic segments: Americas; Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA); and APJC (Asia Pacific, Japan and China). And for the first time perhaps, it has empowered its regional heads to take decisions to serve their markets better.

This change could have a significant impact on India and the globalisation centre. “Five years ago, I was sitting alone in the middle of the night to sell my ideas, now we have a regional office here with Edzard who can take empowered decisions,” says Elfrink.

Two years ago, as Elfrink was getting ready to leave for San Jose, instead of giving his role to any one executive, Chambers decided to appoint an India board, co-chaired by Overbeek, Menon (Deputy Chief Globalisation Officer) and Naresh Wadhwa, president (India & SAARC). Apart from them, there are a dozen other executives from various functions, including senior engineering leads such as Vivek Mansingh and Partho Mishra. The board meets every six weeks. With the engineering team beefed up and falling in place, and two global CTOs paying close attention, product development from Bangalore is beginning to pick up.

Elfrink is still the public face of Cisco’s globalisation strategy. In the re-organisation, Elfrink’s other responsibility, the $8 billion global services business has been moved to Gary Moore, Cisco’s COO.

When Chambers started to focus on India in 2005, the expectation was that India would become a billion-dollar market for Cisco in three or four years. But it’s been seven years and people close to the company say India will close at about $800 million this year. Wadhwa, who took over as country head in 2007, contests that figure, but says Cisco policy does not allow him to reveal the exact number.

But he agrees that the Indian market, much like other emerging countries, is a very dynamic place. “One year we were growing at 30 percent and then next, it fell to 13 percent,” says Wadhwa.

For the last two quarters of this fiscal year (Cisco’s fiscal year runs from August to July), India was the slowest growing market in the APJC region. Wadhwa blames the macroeconomic and political situation in India, and cites an IDC study that says the Indian market shrank by 18 percent just last quarter.

Industry observers though say Cisco’s poor showing in India is partly the result of the drubbing it has received at the hands of Chinese competitors like Huawei and ZTE since 2005. Alok Shende, founder and director, Ascentius Consulting, says that Indian telecom operators have tremendous pressure to keep cost of operations low, which has worked to the advantage of companies like Huawei.

This was exactly the kind of gap that the globalisation centre is now expected to fill. On his visit to Mumbai in early April, Chambers met with the heads of the cable companies. The Cable Digitisation Bill makes it mandatory to digitise all analogue cable networks in India before the end of 2014.

Cisco sees a huge opportunity in this market. In 2009, Cisco acquired a Chinese company, DVN, which makes set top boxes. The Bangalore centre has taken the DVN platform and has customised a product for India. The ARS 901 router launched in February is at least 40-50 percent cheaper than if it were designed in San Jose, claims Wadhwa. Though Cisco will not reveal how much it has sold, it says the product has received good response from Africa and US, where AT&T has placed an order for it.

“I am not saying that we have reached a tipping point, or there are 30 products in the pipeline, but it’s a good start. Now the question is how to take it forward,” says Wadhwa.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)