Catholic Syrian: God's Own Bank

A community bank in Kerala finds the church, a rival and a tycoon from Thailand all interested in its future

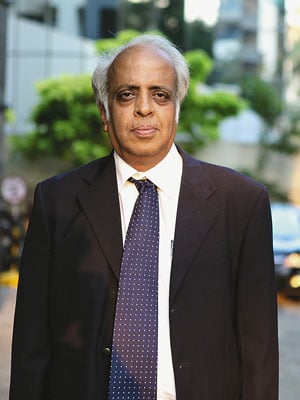

The tropical district of Thrissur in the heartland of Kerala has always attracted outsiders. It was here that Christianity and Islam entered India within years of their founding. But sitting right in the middle of this melting pot of cultures and heading a community bank that represents one of India’s oldest Christian denominations, V.P. Iswardas is in no mood to entertain outsiders. “My job is to focus on my customers,” the man who took charge as the managing director of Catholic Syrian Bank (CSB) last December, says. He is in the middle of a multi-pronged battle for the control of this community bank. Backed by little more than the benign presence of Jesus Christ in a portrait in his office, he is trying to ward off takeover attempts and protect the bank’s independence.

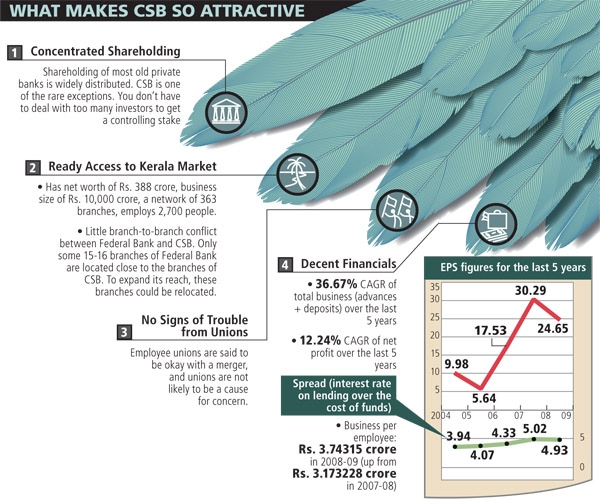

But outsiders, sure as hell, are interested in coming in. CSB has built an exclusive franchise in Kerala with total business of Rs.10,000 crore and 363 branches, reaching virtually every nook and corner of the Malayalam country. For banks and businessmen looking to dominate the financial sector of the state that gets the highest level of foreign remittances in India, it is a tempting buy.

Naturally, there has been no dearth of suitors. Just 80 kilometres from Iswardas’ office sits M. Venugopalan, CEO of Federal Bank. This larger country cousin of CSB has been trying to acquire it for the past two years in a bid to become the dominant bank in Kerala. It bought a 5 percent stake and waited for a larger stake. It found a heaven-sent opportunity when the Reserve Bank of India set a March 31, 2010 deadline for CSB’s largest shareholder, Sura Chansrichawla, to bring down his 24.5 percent stake to less than 10 percent. Here was a shareholder under compulsion to sell and a buyer eager to lap it up. For a while, it almost looked like CSB would become an apple in Federal Bank’s basket.

While further events have put the deal in a knotty situation, names of other Indian businesses and non-banking financial companies constantly crop up as potential acquirers of CSB. Its star-studded shareholders list includes the likes of engineering conglomerate Larsen & Toubro.

Obviously, all this attention irks Iswardas, who wants to retain the bank’s independence and the Catholic Syrian community in Kochi, backed by the church that wants it to retain its community identity. Their answer? To treble the business of the bank to Rs. 30,000 crore in two years, expand its footprint, create a presence in all states in the country and raise money from the market to fuel that growth. Iswardas hopes that this would discourage existing investors from selling out.

While in opposite camps, Iswardas and Venugopalan have one thing in common. Both have to struggle with their respective board of directors that may not always agree with their views. The CSB board will approve a deal at the right price, while Federal Bank’s board won’t allow Venugopalan to pay as much as he was willing to.