BRIC Countries Hit A Wall

The economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China grew at a furious pace for much of the past decade and looked like they would beat even the most optimistic of forecasts. But recent missteps and increased competition from other nations have slowed the momentum

Jim O’Neill’s epiphany came on September 11, 2001. Chief economist at Goldman Sachs then, he had grown up in a working class neighbourhood, south of Manchester in England “getting drunk and playing soccer”.

Three thousand people died that day when 19 terrorists’ owing allegiance to Al-Qaeda, a terrorist group, hijacked four passenger jets. Of these, two were used to bring down New York’s iconic twin towers at the World Trade Center; another one was rammed into the Pentagon, America’s defence headquarters; and one crash landed into a field in Pennsylvania after passengers onboard the plane overpowered the hijackers and a scuffle ensued. An outraged America responded with grief, fury and acts of retribution.

Unlike most people who believed this was a clash of civilisations, the economist in O’Neill argued it was an act of lopsided globalisation. In fact, in January 2010, he’d told the London-based Financial Times that all things global are exemplified by all things American. And that it didn’t feel right to him. “...for globalisation to advance, it had to be accepted by more people … but not by imposing the dominant American social and philosophical beliefs and structures,” he argued. September 11 was his evidence.

He called in his team of number geeks, including Roopa Purushothaman and Dominic Wilson, to interpret the world from this lens. It culminated in a report: Global Economics Paper No: 66. People in business and economics know of it as the BRIC report, with BRIC being an acronym for Brazil, Russia, India and China.

The hypothesis it contained was this: “Over the next 10 years, the weight of the BRICs and especially China in world gross domestic product (GDP) will grow”. GDP measures the total market value of all final goods and services produced in a country in a given year, minus the value of what it imports. “...in line with these prospects, world policymaking forums should be re-organised,” the report said. Therefore, it argued, investors across the world would do well to pay more attention to this block of nations.

Investors across the world took notice and bet their monies on the idea. The numbers prove it.

• In 2000, all the emerging markets put together got $200 billion in private capital investments.

• By 2010, this number had gone up eight times to one trillion dollars. Of this, almost 40 percent found their way into BRIC. In absolute terms, the number continues to grow even though the pace at which capital is coming in has declined since 2007.

All ought to be well, therefore, in Brazil, Russia, India and China, and O’Neill ought to be guzzling the beer down in an English pub. But all isn’t well and O’Neill isn’t guzzling beer. Instead, his hypothesis is under intense scrutiny and O’Neill is busy defending it. It is, therefore, important to closely scrutinise yet another series of numbers.

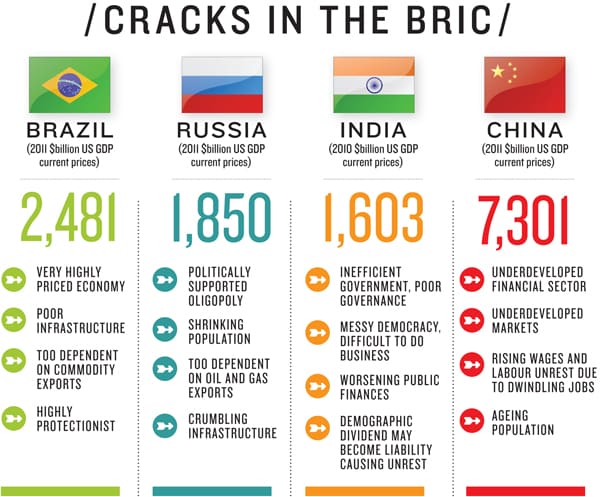

• If you went to the market to buy something using the Brazilian real, the Indian rupee or the Russian rouble, you’d get much less of whatever you want to buy than you could in the recent past. Over the last four months, for instance, the value of the rupee has declined 11 percent. Each American dollar, the currency against which the value of all other currencies are measured by, is now worth Rs 54.4—in economic jargon, the lowest the rupee has gone to. This, in spite of the fact that the American economy stands at a precarious point. By all yardsticks, each American dollar ought not to be able to buy so many Indian rupees. But it can. Add to this the fact that output from India’s factories shrunk 3.5 percent in March this year. That brings India close to the economic crisis it faced in 2008-09.

• It’s much the same thing with Brazil’s real. Since the beginning of this year, it is down 15 percent against the dollar. The country’s economy is shrinking in spite of the Brazilian government’s attempts to give it a fillip by cutting taxes and putting more money into the hands of its people.

• China’s GDP, which was growing at an incredible 10 percent, has slowed down to 8.9. While 8.9 is as good a number as any, it’s a slowdown nevertheless. That is because when GDP slows down, jobs are among the first casualties, and the workforce begins to get restless. In part, this is because the Chinese are cutting down on constructing new highways and railroads. If they slow down any more, demand for resources such as steel, copper and oil will taper and fall into a slump.

• The ripple effects are being felt in Brazil and Russia, both of which are exporters of resources to China. Like we articulated above, the real has already lost a significant amount of its value. And in Russia, industrial production grew just 1.3 percent last month, the slowest in two-and-a-half years.

So, what happens now to investors who’ve poured their money into BRIC? More importantly, what happens to 40 percent of the world’s population that live in these four countries?

It’s a tough world

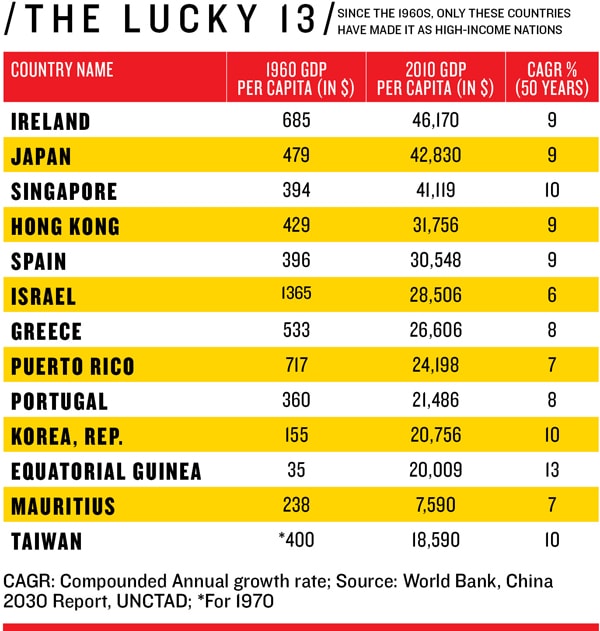

Most countries get a window of five to 10 years to transition from being a middle-income nation to a high-income one. Since the 1960s, only 13 countries out of 101 made it as high-income nations. To do that, they had to grow at 8 percent each year for 50 years. Their people now earn, on average, $29,902.

When these 13 countries started to get out of the middle-income zone, they were five times better off than their BRIC counterparts, all of whom were then poor. Fifty years down the line, the difference remains the same. The 13 countries remain richer because even as the BRIC countries started to grow, they continued to grow at an aggressive rate. If BRIC had to get to be as rich as the high income nations, they’d have to grow twice as fast as high-income nations.

But that was difficult for various reasons, says Barry Eichengreen, an economist, who studied the phenomenon.

Reason #1: Eichengreen’s research indicates growth starts to slow down by 3.2 percent when a country’s per capita GDP touches $16,700. China, he says, will reach that level by 2016 when its GDP will be in the region of $15,000. But with growth rates already slowing down, the problem seems to have hit China earlier than anticipated.

Reason #2: Typically, countries start reaping demographic dividends when fertility rates fall and the dependency ratio declines. This ratio indicates the number of persons who are economically dependent on those who provide for them, either by earning income or paying taxes. The economically dependent are defined as people below age 15 and above age 65.

As an example, Eichengreen cites the example of Ireland, a predominantly Catholic nation where contraception was illegal. But after it legalised contraception in 1980, the numbers of young, dependent people below the age of 15 declined dramatically and in turn helped catalyse the Irish economic miracle in the 1990s. Ireland is today part of the 13 high income countries.

Projections made by a United Nations report indicate that, with India being the exception, the outlook for other BRIC countries on this critical parameter looks bleak.

Reason #3: Smaller countries are usually better at breaking the middle-income trap because they can continue to trade with larger countries and as a thumb rule, maintain good relationships with their neighbours as well. This allows them the latitude to import quality labour without affecting their own demographics and putting a strain on their public resources.

Reason #4: Slowdowns are common in countries where investment rates are high and consumption is low. Example? China. The country avoided the financial crisis because it invested into fixed assets between 2008 and 2010. In 2008, its fixed assets-to-GDP ratio was at 42 percent, which moved on to 50 percent in 2010.

But Nouriel Roubini, also called Dr Doom for his dire projections and one of the world’s foremost economists, went on the record last year and argued on Project Syndicate (www.project-syndicate.org), that no country can be productive enough to invest 50 percent of its GDP into new assets and will eventually face overcapacity and a staggering problem of non-performing loans.

It is tempting to argue here that India, with its per capita GDP at $1,400 is still far away from the $17,000 mark. But problem is, productivity gains, especially from labour, have begun to plateau.

Reason #5: The go-go years between 2003 and 2007 had given BRIC countries a lead over other smaller emerging markets. They could have used the surpluses to make changes. Unfortunately, they didn’t. “The BRIC countries should have initiated some of the more stringent policy measures while global growth was strong, and are now feeling the pain from delaying difficult political decisions,” says Roopa Purushothaman. Consider each one of them

• Brazil: High commodity prices of iron ore, soya beans and sugar have helped drive massive inflows. But instead of building infrastructure, it is intent on building a welfare state. In his book, Breakout Nations, Ruchir Sharma talks about CEOs in Brazil building a network of helipads on office skyscrapers so that executives don’t have to waste hours in traffic jams.

• Russia: More than half of its citizens depend on the state for a living and wealth is concentrated. It has more than 100 billionaires of which 69 live in Moscow alone.

• India: Its biggest advantage, economists reckon, is entrepreneurial talent. But in 2006, Indian entrepreneurs invested $7.8 billion in businesses outside the country. The number more than doubled last year to $16.8 billion.

The second worry is India’s inability to increase its global competitiveness, which is reflected in its persistent current account deficit. What it means is that India’s total imports of goods and services are higher than its exports, which makes it a net debtor to the rest of the world.

“Fiscal and current account deficits are becoming more structural not just cyclical and that’s a worry for a country like India,” says Sanjay Nayar, CEO of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, India (KKR), a private equity firm.

For many years now, India has been funding its current account deficit with foreign capital. India needs oil for which it pays in dollars. And Indians love gold, which is imported in large quantities, and are paid for in dollars. The only business that brings in the dollars is the IT services business.

But points out Martin Wolfe of the London-based newspaper Financial Times, India took to services way too early in its growth track. Typically, countries that have continuously moved up the GDP track first built their infrastructure and then move into services. India, on the other hand, left manufacturing, power and infrastructure half way and became a services leader without taking on infrastructure.

“Overall, the Indian economy is the most exposed of the BRIC nations to episodes of risk aversion and the subsequent outflow of foreign capital. In contrast to the other BRIC economies, India does not reap much benefit from depreciation in the value of the rupee, as it is not a major exporting economy,” says Richard Gibbs, chief economist at Macquarie.

• China: For its size, China has suitably large problem. It needs to overhaul its political and social systems. Nobel laureate Ronald Coase and Ning Wang of Arizona State University have pointed out that in China the production and dissemination of ideas are still controlled by the state. This leaves little room for private universities, independent research institutes, and free academic societies. “Without an open market for ideas, the talents and creativity of one-fifth of human population remain under-explored,” say Coase and Ning.

The paradox, says Lief Eskeson, chief economist for India and Asean at HSBC, is this: China and India need to do diametrically opposite things to build sustainable growth models. India is a labour abundant country and can concentrate on manufacturing while China will have to take a deeper look at its services and domestic market.

Even as these problems bubble over in BRIC nations and they are busy trying to stare their problems down, global companies and investors are impatient as they are now looking for new places to funnel their money.

The new contenders

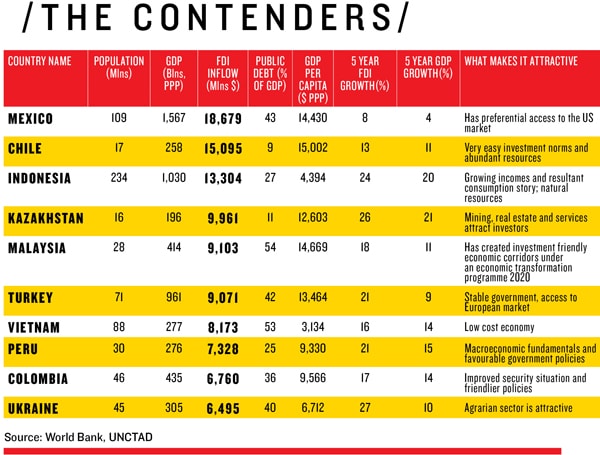

Turkey, Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, Vietnam and the GCC economies of the Persian Gulf are now being looked at with much gusto. The emergence of these new places to do business comes at a time when the world is going through a sustained period of deleveraging—simply put, when you have to repay your debts to make yourself attractive to investors. That makes competition for foreign direct investment (FDI) and foreign institutional investment (FII) dollars a lot tougher.

According to a McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) study, deleveraging is not going to be pretty. These episodes are tough and last six to seven years on average and reduce the ratio of debt to GDP by 25 percent. This measure gives an idea of the ability of a country to make future payments on its debt. The higher the debt-to-GDP ratio, the less likely the country will pay its debt back. When a country starts working on repaying debt, its GDP typically contracts during the first several years before it recovers. “If history is a guide, many years of debt reduction are expected in specific sectors of some of the world’s largest economies, and this process will exert a significant drag on GDP growth,” says the MGI study.

In turn, this means capital will be scarcer over at least the next three-four years because every nation will want it, whether rich, emerging or poor. The rich nations need money to reduce their debt burden, support ageing populations and build new infrastructure. “...but capital will be more discerning,” says KKR’s Nayar.

Which is why the new contenders look attractive. Each comes with their advantages. Turkey straddles Asia and Europe and has had a stable government for long. Turkish premier Recep Tayyip Erdogan won a second, stronger mandate last year on the back of economic performance as well as political consolidation.

Indonesia makes it very easy to do business. Its banks are now really cautious after their experience of the East Asian Crisis. And its president Susilo Bambang Yudhyono has somehow managed to bring together 245 million people of dozens of different ethnicities to see a common goal. Sri Lanka and Myanmar are both getting investments because peace now reigns there.

These countries have not had it easy. Indonesia climbed out of the rubble of the East Asian Crisis of 1997. Its GDP was around $215 billion in 1997. It plunged to $140 billion by 1999! One would have expected Indonesia to have been down for the count. Today Indonesia’s gross national income (GNI) is almost $700 billion. GNI is measured by adding a country’s GDP and the income it receives from other countries.

Indonesia is a net exporter of oil and gas. But with Chinese wages rising, manufacturing is shifting to Indonesia because unskilled labour is cheap. Tourism too is bringing the dollars in because of the growing popularity of Bali, Lombok, Bintan, and historical sites in Java. Indonesia is targeting the high value tourist rather than the backpacker crowd and that is reflected in its hotel and resort development.

Turkey rediscovered its position in world strategic affairs in the aftermath of the US war on terror, as it increasingly became important to both the Islamic as well as the Western world. A decade ago, the country’s budget deficit was 16 percent of GDP. But last year, the country slashed that number to 3.6 percent. The country’s inflation rate was 72 percent a decade ago. It is now down to eight percent. Its GDP is now more than thrice what it was in 2002. One of the key themes has been privatisation in telecom, energy and infrastructure.

This is not to say they don’t have problems. For starters, the individual markets are small and in most, purchasing power is concentrated at the top end of society. Indonesia is the biggest market among them. But it suffers from endemic corruption, infrastructure bottlenecks and difficulty in land acquisition.

Mexico is run by monopolies where the top 10 families account for a third of the stock market value and the country’s economy is too dependent on the US’.

The long-drawn battle with drug lords continues to drain the country’s energy.

The GCC economies are overly dependent on oil income and are hardly building world-class industries or institutions.

But these nations have been quick to acknowledge their problems. The traditional advantages of BRIC—demography, large market, entrepreneurs—exist here too. “All those countries are looking quite good in terms of economic growth, capital market development and financial strengthening,” says Mark Mobius of Templeton.

It is a tough ask, though. The reason why the idea of BRIC was so appealing when it was first proposed was the four countries put together had the right ingredients—a burgeoning consuming population, resources, stable governments and a vast labour pool. “The BRICs were chosen to reflect a pattern of global demand shifts that are occurring among a number of large economies in the developing world. It’s not a zero sum game,” says Purushothaman. However, they were heavily dependent on US and European consumption for their growth. “If an economy suffers from shortfalls in these flows, it’s still largely due to individual conditions or policy decisions,” she adds.

For instance, 65 percent of India’s exports last year were to the two regions. As long as their consumption appetite was high, China kept producing goods fuelled by oil and ores supplied from Russia and Brazil. When the two regions went into a slump, the world’s factories slowed down. For a time though, many expected China and India to generate enough demand to fuel consumption. They did too. But the two had no hope of matching the US or Europe in the value of consumption.

Prof Sreeram Chaulia, dean at Jindal School of International Affairs, says that for BRICS (the S stands for South Africa, which was included in the BRIC group in 2010) to progress, the initiative has to come from the governments as none of them are advanced capitalist societies. “The BRICS model will be more state-ist because none of them have a dominant private sector.” And there lies the catch.

India, China and Russia particularly will have to give more leeway to the private sector in their respective economies and move to create robust markets. Among the three, only India has strong markets and allied institutions.

But all of this hasn’t affected the optimism of India’s policy makers. Addressing the UN General Assembly debate on the “State of the World Economy and Finance in 2012” in New York last week, the Planning Commission’s deputy chairman Montek Singh Ahluwalia said India could grow at between 8 to 9 percent for the next 20 years, provided it had a supportive global environment.

Even economists like Jim O’Neill and seasoned investors like Mark Mobius believe there is nothing wrong with the BRIC countries. O’Neill, who first thought up the idea of BRIC as a block, continues to remain optimistic. “So far, all four have outpaced what I had assumed in 2001 and 2003 in terms of their growth.” Mark Mobius seconds him. “They [BRIC countries] are all [still] attractive since we are finding companies in all the countries that we would like to buy.”

On another note though, Ruchir Sharma’s own experience is the most telling. In 2010, Sharma, then an emerging market strategist at Morgan Stanley wrote a cover story for Newsweek magazine called “India’s Fatal Flaw”. The flaw, he argued, was crony capitalism. When he visited India next he got an earful from the bureaucrats. “I was asked ‘Why are you writing this nonsense?’” says Sharma.

But Roopa Purushottaman says: “Yes. India has disappointed in tackling the structural issues that are most important—investment and education—but the prospect of turning potential into reality is still as compelling as ever.”

To sum it up, there is potential, and lots of it. Now, if only, policy makers can get past the wilful blindness that seems all pervasive.

(Additional reporting by Cuckoo Paul in New York and Sujata Srinivasan in Connecticut)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)