Ashish Guha is Rebuilding Heidelberg Cement India

As CEO of HeidelbergCement India, Ashish Guha often dips into his two-decade-long investment banking experience. But rebuilding a cement company has also meant a fair bit of unlearning, he says

As an investment banker, Ashish Guha was known for his promptness in closing deals. The most famous of these was a 12-day affair in 2001, when he advised Sunil Bharti Mittal to acquire Spice Cell, owned by fellow billionaire BK Modi. Apart from the pace, it was the finish that gave him a high. As Guha says, “The sweetest part is closing a deal, especially when the conversion rate in investment banking is two out of 10!” Guha was scoring high on that parameter when a dramatic shift took place in his career in 2006.

It all started after he had closed yet another deal. This time around, Guha was advising German cement behemoth HeidelbergCement AG in its acquisition of the SK Birla-owned Mysore Cement. While congratulating Guha on a deal well struck, Daniel Fritz, who headed the multinational’s Asia Pacific market, added an offer: He asked Guha if he would be willing to take up the position of CEO and managing director of HeidelbergCement India (HIL). Apart from Mysore Cement, the new entity would include Indorama Cement, which the German company had bought earlier.

Challenge Accepted

This was a tough ask for Guha. Mysore Cement, now HIL, had been profitable only once in 15 years. Though the deal was designed such that the company would come out of the clutches of the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction, it would still take a mountain of effort to turn it around.

Its brand Diamond was languishing at the bottom of the market and was known as ‘contractor’s cement’ because of its low price and poor quality. There was hardly any synergy between the units that functioned as separate companies; the morale of the workforce was uninspiring. Despite these hurdles, Guha, who had spent over two decades in investment banking, said yes. His family and friends were taken aback–even shocked. “I agreed because I liked the challenge. I also had the comfort of knowing I could go back to investment banking if it didn’t turn out well,” says Guha.

In reality though, going back was not an option. The 56-year-old had staked his reputation on this job. As Guha himself points out, while closing a deal is sweet, what makes it sweeter is if it turns out to be a win-win for both the seller and the buyer. Mysore Cement had been relatively cheaper at a valuation of $80 per tonne as against $180 per tonne that Heidelberg was willing to pay for another local cement maker. Guha had to make sure the acquisition also paid dividends in the long run. The newly-appointed CEO and MD had two things going for him. One, there was some low-hanging fruit that could immediately benefit the loss-making cement maker. Second, he had a clean book to start with as the new company was not carrying the burden of legacy, or debt, from its past owners.

Today, seven years later, Guha has still not felt the need to go back to investment banking. HIL turned operationally profitable within a year of his stewardship. In the following year, it reported net profits for the first time since 1996.

The financial performance has been impressive. From a top line of Rs 517 crore and a loss of Rs 90 crore in 2006, the company touched revenues of Rs 1,114 crore and net profits of Rs 30 crore in 2012. Its capacity has increased from around 3 million tonnes to 6 million tonnes per annum, thanks to expansion efforts. This change has reflected in its reputation too. Its new brand Mycem, which replaced Diamond, now sells in the upper B segment (cement brands sell in A, B and C category) and is close to matching the pricing power of heavyweights like ACC and UltraTech Cement.

Despite the upturn, Guha admits to not having won the battle entirely. This is evidenced by the financial results of the second quarter of FY2013 (HIL follows the calendar year). Pankaj Pandey, head of research at ICICI Direct, says in his August 2013 report: “Heidelberg Cement’s Q2CY13 results remained below our estimates with net sales of Rs 358.6 crore and net loss of Rs 8 crore…” He says power and freight expenses went up (year-on-year) by over 8 percent and 14 percent, respectively (on a per tonne basis), due to hikes in tariffs, railway freight and diesel prices. As a result, the report adds, Ebitda (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation) per tonne declined to Rs 334 per tonne from Rs 478 in quarter two of 2012 and Rs 382 in quarter one of 2013.

If the cost pressures were not enough, the cement industry, despite consolidation over the past few years, is still largely fragmented. This has hurt its pricing power, made worse by a supply glut following aggressive expansion projects by players who were banking on a booming economy. “When we invested in capacity addition, we had estimated a GDP growth rate of 8 percent. But it is nowhere close to it,” says Guha. And as his sales and marketing director JN Cooper adds, Mycem is today sandwiched between bottom-of-the-pyramid players, on the one hand, and A-level players, on the other. “This makes us vulnerable to both sets of competitors,” says Cooper.

Having won the first round, Guha is now focusing on the second, which will be mainly about improving profitability and taking the brand to a new level. “Unless I increase margins, I won’t be able to attain that sweet spot,” he adds. He has some definite plans on how to get there—but first consider his first round strategy.

People and processes

In some part, Guha drew on the investment banker in him to do well as a CEO. To understand where the company stood, he started benchmarking—an oft-used tool in investment banking—HIL against the competition. He found several shortcomings. For instance, to give marketing a boost, a new brand had to be created in order to command a better price. But that would need an improved product from well-equipped plants. Procurement had to be integrated across the four units, in Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh, to save costs. Manpower too had to be rationalised.

To begin with, however, the attitude of his staff had to change; Guha had to align them to one vision. This task, which he would later term as his “toughest”, finally saw him shedding his investment banking past completely. “As an investment banker, you advise people. Here I had to get on to the ground myself,” he says about his unlearning. Luckily, as a son of a bureaucrat, Guha was not short of exposure to people from all walks of life. He was popular during his campus days at Jadavpur University, Kolkata, as a sportsman and a student politician; he was always surrounded by people, building strong relationships. Even in investment banking corridors, he preferred to keep his collar open rather than wear a tie.

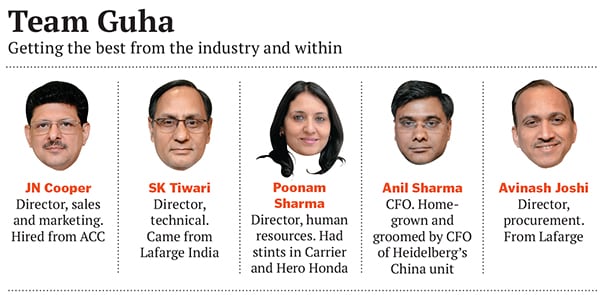

Guha would station himself at the plants for 15 days a month, talking to managers and workers. As his spoken Hindi improved, he shared his mobile number freely so that anyone could call him at any time. Simultaneously, he shifted some of the key functions from the plant level to the corporate office in Gurgaon. This included finance, human resources and procurement. A new senior management was created, drawing from the best talent in the industry. Help also came from the parent company. The CFO of Heidelberg’s China unit was deployed in India for two years before the current incumbent Anil Sharma, who was earlier stationed at one of the plants, was groomed to take over the key role.

Many of the initiatives, common otherwise, were radical for the company. “We never had a customer service department,” says Cooper. The HR team, led by director Poonam Sharma, undertook training projects. “This,” says Sharma, who had joined the company in 2002, “had never happened in the past.” At the plant, the team borrowed best practices from the parent company. Limestone from multiple mines were typically mixed for better efficiency. While, earlier, the cement had around 20 percent of fly ash, it was increased to 33 per cent, says SK Tiwari, director, technical. Procurement policies also changed with a penalty clause added in the coal supply pact that would be implemented if the quality of the raw material was below the contracted benchmark. Procurement director Avinash Joshi says: “Earlier, there was no check on quality.” Each of these steps improved margins.

Inexplicably, the company would sell its 2.5 million tonnes of annual capacity to far-flung places like Punjab, Himachal Pradesh and eastern Bihar. Logistics expenditure touched nearly 25 percent of total costs. This was cut back on; the company started selling more than half of its produce within a 200 km radius of its plants. “Now the logistics cost is half of what it was earlier,” says Cooper. (See box for more details on turnaround initiatives). Even the dealers, whom Guha and Cooper now meet regularly, are taking note. “They hold training workshops for us also. A lot has changed,” says Man Singh Choudhary, HIL’s exclusive dealer from Hathras, near Agra in Uttar Pradesh.

Yesterday Once More

By 2009, HIL’s revenues increased to Rs 981 crore. The most telling change was in the bottom line. Net profits stood at Rs 134 crore and the Ebitda margin went up to nearly 18 percent. The margins might have been lesser than the bigger players in the sector, but the turnaround had happened. It reflected in HIL’s scrip at the Bombay Stock Exchange—up from Rs 28 to Rs 42 a share during the same period.

But the instability in the economic environment didn’t let Guha rest for long. Just as the added capacity came on stream earlier this year, demand has gone flat, forcing Guha and the rest of his peers in the industry to reduce prices. The price ‘correction’ though is yet to happen in fuel costs, squeezing HIL’s Ebitda margins; they are now below 10 percent. The company scrip is back to sub-Rs 30 a share.

Guha and his team are now attacking on several fronts. While Cooper and the marketing staff are looking to enhance brand perception by introducing a mascot (instead of a celebrity endorser that has become a norm in the industry), the senior management is formulating ways in which to further reduce the workforce to improve productivity.

To ensure stocks don’t pile up, the sales team is increasing the percentage of bulk sales of cement to customers directly.

And as far Guha is concerned, he is once again donning his dealmaker hat. On the one hand, he is selling the grinding unit in Raigad to the Sajjan Jindal-owned JSW Steel. On the other, he is also looking at probable targets that will add to HIL’s capacity. “There are options for acquisition and we are looking at them,” says Guha, keeping the details under wraps like a ‘typical’ investment banker. Mostly though, he is looking for that sweet spot again.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)