A Salve for a Taxing Moment: The Vodafone Inside Story

How Vodafone won the tax case: The inside story of the courtroom battle

The court hearings had gone on through all of August. On September 8, 2010, the Bombay High Court was packed to the rafters with newspaper reporters of all hues. There was a battery of lawyers representing the Government of India and telecom giant Vodafone. There were two judges who had been hearing the famous Vodafone tax case: D.Y. Chandrachud and J.P. Devadhar. Though Devadhar was in Nagpur that day, he was ‘virtually’ present through a video link. Vodafone’s tax spearhead Desmond Webb was there.

“Most reporters who had covered the hearing passed around early congratulations to us. They believed our counsels Harish Salve and Abhishek Manu Singhvi had done enough for the Bombay High Court to rule in our favour,” says a former Vodafone employee who was present in the courtroom.

As the judgement began to be read out, there was some buoyancy in the Vodafone camp. The two judges did not think that Vodafone’s purchase of Hutch’s business was done in a manner to avoid taxes. The two judges also said that the shares that gave Vodafone control over Hutch’s telecom business in India were registered outside the country—in Cayman Islands. And then they turned their attention to the specific issue on which they were supposed to pass a judgement—that Indian tax authorities simply did not have any jurisdiction, any basis to even analyse the transaction. The judges said while they were convinced that Vodafone’s transactions were genuine, they were also quite sure that such a complex transaction needed more investigation. This was Vodafone’s Javed Miandad moment. The match was lost on the last ball.

“We could not have been more disappointed. Three years had passed by and we had provided so much information and yet the issue was not settled,” says a Vodafone executive.

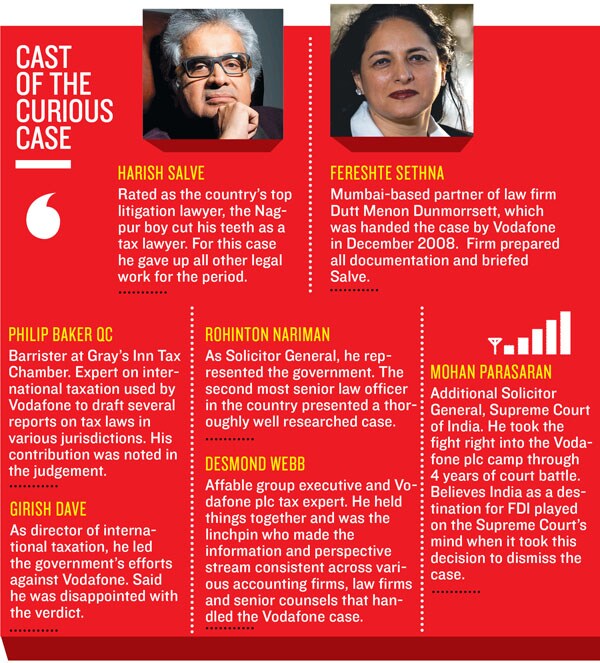

The two people who were slugging it out—Mohan Parasaran on the side of the government and against him Harish Salve who was representing Vodafone—were both not there in the court that day. That would have to wait for another day.

Perhaps no case in corporate history has evoked as much interest as the Vodafone tax case. For all the right reasons, one might add. For the first time in the history of free India, the Indian tax authorities were going after a fat-pursed multinational that had bought a business in India.

In 2006, the Indian mobile telecom market was growing very rapidly. Every month more than 10 million subscribers were signing up to own a mobile connection. If you were a global telecom company, you had to have a piece of the Indian telecom action and you had to buy one of the top firms because in this industry bigger players make more money.

The top dogs in the Indian market then were Bharti Airtel, Reliance Communications and Hutchison Essar. The former two were not selling. Hutchison was owned by the Hong Kong tycoon Li Ka-Shing and he was interested in exiting the business. Vodafone, the British telecom company, wanted to come into India. But others too wanted to buy Hutch to increase their market share. Reliance Communications definitely made a play for the firm. It was a tight finish and on February 12, 2007, Li Ka-Shing accepted Vodafone’s bid and Hutch was sold. That should have been the end of the matter. As things turned out, the sale was just the beginning.

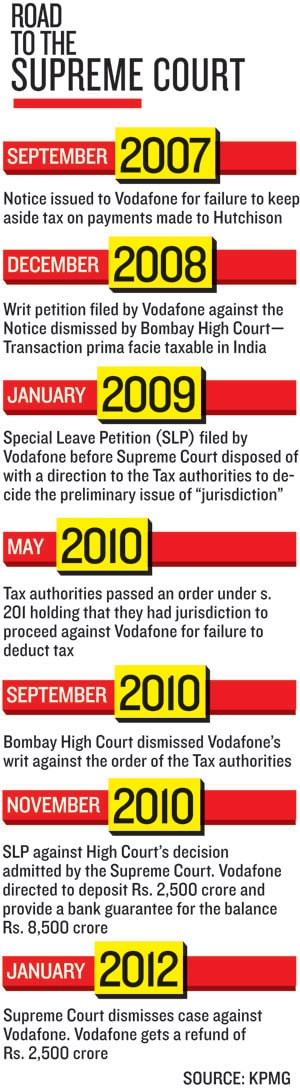

In September 2007, the tax authorities sent a letter to Vodafone. It had just one question for the British firm. Why hadn’t it kept aside money due to the Indian Income Tax Department? The first reaction in Vodafone headquarters was: “Huh? What taxes?” Indian tax authorities were only too happy to point out that while Vodafone and Hutchison Whampoa had done the deal outside India, in effect it involved the sale of an Indian asset—Hutchison Essar India Limited. Since Li Ka-Shing had made such a handsome profit on the sale, he should have given Vodafone the capital gains tax due on the transaction to keep aside for the Indian taxman.

“The only thing that the senior management at Vodafone thought is ‘this is absurd!’ There is no precedent for this anywhere in the world. Why is the Income Tax Department coming after us?” says a Vodafone senior manager.

What they didn’t know then was that one of Income Tax Department’s finest minds, Girish Dave, had been thinking about how India could benefit from mergers and acquisitions activity that involved an India angle. Dave retired from the department in 2010, but he was the director of international taxation at Mumbai between 2005 and 2009. That was when he decided to bell the offshore cat.

More surprise was to follow. In the Union Budget of 2008-2009, the government gave a new meaning to something called “assessee in default”. Normally, this rule would apply if someone had collected taxes on behalf of the government, but forgot to deposit it with the government. For example, a company that had deducted income tax from its employees’ pay, but did not give the government that money. That was “assessee in default” before 2008. But after 2008, even if you were supposed to collect taxes on behalf of the government and had not collected it, you became “an assessee in default”. And this change would become effective from June 2002—five years before the Vodafone deal happened.

Sniggering chartered accountants called it the Finance Ministry’s “Vodafone Amendment”.

Vodafone decided to play the game with all the flair of Alistair Cook. They took the issue straight to the court. That’s when Girish Dave’s court alter-ego came into being: Mohan Parasaran, the additional solicitor general, Supreme Court of India. This sharp lawyer practiced in the Madras High Court in various branches of law and was also a professor of law at Presidency College. He became what Vodafone claimed about its network: Whichever court the company went to, Parasaran would follow them.

And to courts they went, many times over (see timeline). In September 2008, Iqbal Chagla was Vodafone’s counsel but he couldn’t get the courts to keep the tax authorities at bay. In the January 2009 hearings Vodafone had Fali Nariman represent it in the Supreme Court, which directed the case back to the Bombay High Court. Through 2008 and 2009, the courts maintained that, on the face of it, the Indian tax authorities were well within their right to pursue the case against Vodafone. So Vodafone’s opening gambit that the Indian tax authorities had no jurisdiction over the transaction, failed.

Vodafone then brought in two new counsels for the August 2010 hearings in the Bombay High Court: Harish Salve and Abhishek Manu Singhvi. While Salve could not convince the Bombay High Court to drop the matter he did improve Vodafone’s position. Judges Chandrachud and Devadhar did not find the transaction to be a sham and set up in a manner to avoid taxes.

The final task of improving the positional play of Vodafone would be the task of this boy from Nagpur, who the Nagpurians say is more of a Delhiite now!

If you had to prepare a list of the top 10 lawyers in the country, Harish Salve would easily figure on it. He is described by some as a “legal robot”, which is perhaps a recognition of his methodical execution. Salve has represented most high profile politicians, big business such as Reliance Industries, and even states. He is counsel for Kerala in the Mullaperiyar Dam case.

His father N.K.P. Salve was once a Congress stalwart from Vidarbha, Maharashtra, and also a successful chartered accountant. His firm Salve and Company still exists. Harish Salve grew up in affluence in a bungalow near Mount Road, in Nagpur. By a happy coincidence that house stands right behind Saraf Chambers, which houses the Income Tax Department offices!

Salve studied commerce at G.S. College of Commerce and then just moved across the road to study law at Government Law College. In doing that he followed in the footsteps of his grandfather who was a lawyer and then went to do his chartered accountancy, just like his father. That gives him a formidable preparation to work as a tax lawyer. But more than his education it is his interests that probably make him the lawyer that he is today.

“Harish loves forests; he loves music—both Indian and Western—and he is very down to earth. Even as a child he would never let his friends feel that he was privileged,” says Shashikala Salve Meshram, his paternal aunt. “We were going to his house recently in an auto rickshaw and the driver asked about him and said ‘Harish bhaiyya and I have played cricket together’,” she says.

Throughout his career he has taken up cases that show his sensitivities. He took it upon himself to get the Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act [POTA] charges dropped against the Godhra accused. He also got the Delhi Development Authority [DDA] to stop hacking trees at Delhi’s Siri Fort Complex.

It is perhaps his injustice compass that made him take up the Vodafone case after the Dave-Parasaran duo had made life rather difficult for Vodafone. Salve felt that the stand taken by the Income Tax Department was very counter-intuitive. “Why do you want to tax these companies? For 10 years you allowed them to set up a Mauritius company, and now when they sell upstream the government says this should be taxed. The whole thing sounds very wonky. This is wrong,” he says.

He was approached by Hutch, which was an old client. Initially, there was a difference in the way Hutch and Vodafone perceived the case. But both the firms decided to work together and worry about who would pay the liability at a later date. “So in the first round I think Hutchisson was kept out and Vodafone was unhappy with the result. They dropped the legal team and went to Dutt Menon Dunmorrsett [DMD]. In May 2009, I was approached and they decided to work together and it paid dividends,” he says.

After the setback in the Bombay High Court in 2010, Salve made sure that the preparation was even more thorough for the final showdown in the Supreme Court. At any given time there were 8-14 associates working on the case. These are the ones that were present in court. In terms of the documentation, they prepared 8,000 pages that were filed on the record before the court.

There were 26 volumes of judgements that were submitted. The lawyers had the entire compendium of Income Tax Reports in court that they could pull up at any given time. Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday were the days of the hearing and so these were brought to the court on Monday night and taken back on Thursday evening. The documents which were put in 66 bags took eight car trips every week to take to court.

On admission days, that is Monday and Friday, a senior lawyer like Salve would have about 20 matters. Out of this he would make it to court for say, 15. Then on the final hearing days (Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday) he would have just one matter. So the opportunity cost of this case was huge for him. He gave up everything between August 2 and October 19, 2011, when the case was argued (except in the rare case where he just could not say no to a particular client). He went to London to prepare for the case and was on call 24x7. “I have a flat in Mayfair [to prepare for the case]. I find life very orderly there,” says Salve.

Harish Salve: Amit Verma; Fereshte Sethna: Manoj Patil for Forbes India

The government (tax authorities) maintained the same line and length that they had done for the past four years. “Amongst the IT Department’s fundamental assertions was that this was a sham and fictitious transaction devised to avoid tax,” says Fereshte Sethna, partner, Dutt Menon Dunmorrsett. That also raised the stakes for the government because it had to prove this as a sham transaction. No mean task given the level of preparation of the judges.

Justices S.H. Kapadia, Swatanter Kumar and K.S. Radhakrishnan were very well prepared. They knew that they were going to be deciding on a seminal tax case. Justice Kapadia himself being very knowledgeable on tax matters would ask a lot of questions. “On a particular occasion, the Bench indicated having researched international tax law material over the Internet, based on which queries were put regarding the position prevalent in Japan. Often, prior to commencing arguments on a given morning, questions from the Bench entailed 30 minutes to an hour. Senior Counsel Harish Salve answered these, before continuing arguments that day,” says Sethna.

Vodafone also made Philip Baker available as an expert witness. He is an internationally recognised authority on tax law and he filed two expert reports. As and when issues arose before the courts, he would provide answers. In effect, he helped the judges understand what tax laws in other jurisdictions are.

Finally, the arguments came down to two basic issues. The first issue was about whether Hutch sold assets like telecom licences, brand and towers in India as opposed to a sale of shares. The tax authorities maintained that while Vodafone gained control over Hutch’s India business when it bought a Cayman Islands registered company called CGP, all the value of CGP came because of its control over licences, brand, towers and infrastructure owned by the India business. The Supreme Court Justices were quite unequivocal in saying that a share is not distinct from an asset. Once you own the share the asset automatically comes to you.

That brought into play the next line of defence from the tax authorities who said that the location of all the value of the share was in India. The Supreme Court Justices said that the share that gave control to Vodafone was CGP’s and that was located outside India. The tax authorities said something to this effect: “But that company CGP has nothing. It is just a shell company.”

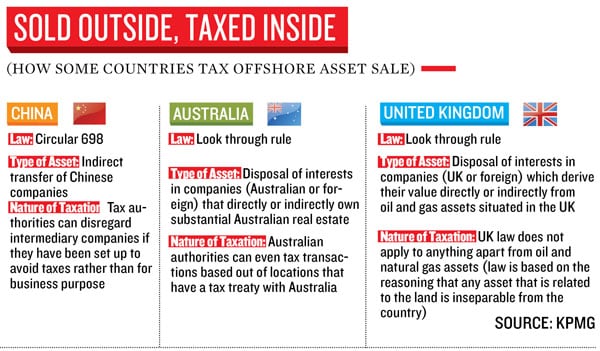

To which the justices said—and this is important—that the law of the land does not say anything explicit about that. They said that the courts were here to interpret the law, not make it. “It is for a country to decide what it wants to tax. Under the DTC [Direct Tax Code] there is a specific provision that if you acquire upper tier shares and 50 percent of the value of the transaction is in India, then it is liable to be taxed on a pro rata basis. But it isn’t a law as yet,” says Dinesh Kanabar, deputy chief executive officer and chairman tax, KPMG (India). China, UK, and Australia do tax such transactions (see graphic on page 50). Salve is quite candid about the letter of the law. “If the Chinese income tax officer said that this was not genuine tax planning, Vodafone would have had to reach out for their cheque book,” he says.

But India is not China. Vodafone and Hutch created a business structure based on existing India laws. The final word on the matter can well be that of Justice K.S. Radhakrishnan who said: “The Revenue has failed to establish both the tests, Resident Test as well the Source Test.”

So, on January 20, 2012, Salve and Parasaran were both in the Supreme Court to hear something that consumed a good part of their time. When the judgement was announced, Justice Kapadia came into the courtroom with two sheets of paper at 1.15 p.m. on January 20 and started reading from the paper.

It took him about 15 minutes to read and the team was on tenterhooks till the 12th minute as they had seen the Bombay HC order where the last bit of the judgement had gone against them.

It was only after the 12th minute when Justice Kapadia came to the operative portion of the judgement that they knew they could celebrate. The Vodafone team was ecstatic! And did Salve celebrate? “No no, I did not. The judgement came at 1.15 p.m., I had rushed to [Delhi] High Court and finished at around 4.30 p.m. and then came back home. When you work very hard for an exam and you do well, you like it,” he says.

Spare a thought for both Dave and Parasaran who put in a great effort. Salve does, that’s for sure. “The tax authorities had prepared well and argued well. It was not one of the cases where it was open and shut on any issue. In fact, when I came out of the court, I said it could go either way. If you are a good lawyer, you are a salesman of ideas,” says Salve.

For Dave, this was an innings well played. “The Solicitor General [Rohinton Nariman] who argued the case for the Revenue, did an excellent, unparalleled job, put the issues before Hon’ble Court in an inimitable way, but missed only in adopting the strategy employed by the other side who went on repeating to the extent of nausea in repeating, repeating and repeating way on issues like (1) look-through provisions,(2) FDI & (3) the way multinationals operate businesses globally.”

Parasaran, who almost won the day for the tax authorities, says: “I think the Supreme Court also went by how the case would affect FDI and investor confidence. This was one of the main factors I think. But in my perception no foreign investor will run away from India as everybody can make a profit here. Our country did not survive just because of FDI.”

According to Parasaran, both sides presented their case before the Supreme Court in an exceptional manner. “Salve was able to present the case from a macro as well as micro perspective and argued extensively.”

None of these legal eagles expect the matter to be raked up again. The zoozoos can cackle in comfort.

(Additional reporting by Bharat Bhagnani & Shishir Prasad)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)