Sanjay Agarwal: Building ground up for the hinterland

With a net worth of $1.3 billion, Sanjay Agarwal debuts on Forbes's list of world's billionaires. His AU Small Finance Bank aims to be counted

among its larger peers over the next decade

Image: Mayur Teckchandani

Image: Mayur Teckchandani

By 2017, Sanjay Agarwal had spent two decades handing out automobile loans. While he admits the first decade had been slow, the venture grew rapidly in the next and was on its way to carving out an enviable niche as a non-banking finance company (NBFC). But the 50-year-old first generation entrepreneur who founded the company in 1996 as AU Financiers had seen first-hand the problems firms like his face when raising money. A lack of financing (and poor quality loan book) had proved to be a death knell for several peers.

At the same time, the mandarins at Mint Street wanted to further their pet cause—financial inclusion. Banking needed to be taken much deeper to small-town India, and while scheduled banks had pitched in over the last four decades, large swathes of Indians were still dependent on moneylenders and their usurious rates of interest. Enter small finance banks that were regulated by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

“We knew that NBFCs could never be a main platform as raising money is a challenge, professionals prefer to work for banks and borrowers will always go to banks first,” says Agarwal. At the same time, AU Financiers had a two-decade track record of making loans and collecting on them. Agarwal raised his hand for consideration in 2017. In all, ten banks were licenced with AU Small Finance Bank being the largest (AU is the periodic symbol for gold). It was the only NBFC out of 72 applicants chosen by the RBI. “Suddenly a much larger field opened up for us,” he adds.

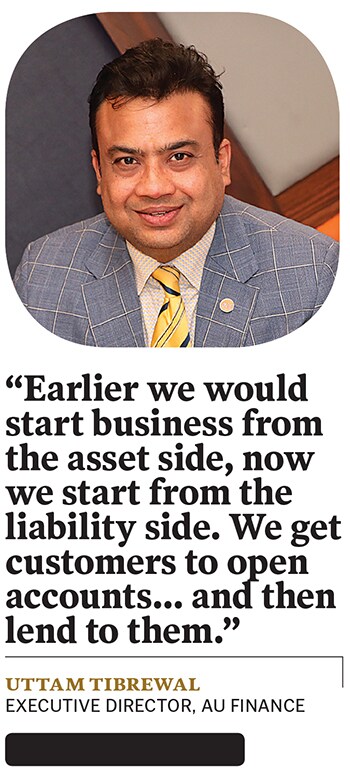

Since it received its licence, AU has continued to prove its mettle and provided a case study in how smaller banks with the right systems and processes can grow rapidly. At a time when there is fierce debate on whether corporates should be allowed to run banks, it is entities like AU Finance and peers like Equitas, Suryoday and Jana, among others that have shown how it is possible to get more people under the banking net without increasing systemic risk. Importantly, these banks are modelled on raising liabilities from urban India and deploying them in an asset base in smaller towns and cities.

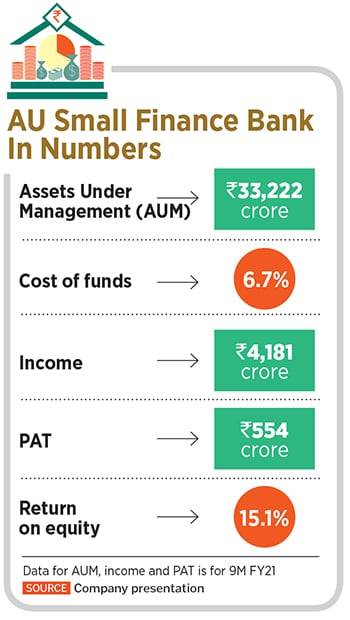

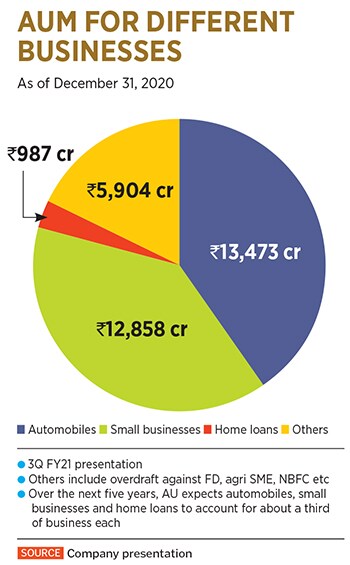

Since it was given a small finance bank licence in 2017, AU’s loan assets have more than trebled from ₹10,734 crore to ₹33,222 crore, and revenue has moved up from ₹1,280 crore to ₹4,286 crore, an annual growth rate of 35 percent. For now, bad loans are under check with net non-performing assets (NPA) of 0.2 percent. While this could rise once the moratorium ends [the RBI moratorium has ended, but NPAs will be disclosed only during the quarterly results that haven’t been announced yet], the bank insists the numbers are under control. In fact, the resilience of its book has given it the confidence to grow equally rapidly once the pandemic is behind us.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

The potential for growth has catapulted AU Small Finance Bank to a market capitalisation of ₹33,700 crore ($4.4 billion), with Agarwal’s 28.8 percent stake worth $1.3 billion, making him a new Indian entrant on the Forbes Billionaires List. With 6 percent of the bank owned by employees, he’s also shared his wealth and recently set up a foundation donating 25,00,000 shares worth ₹260 crore. But Agarwal, who colleagues describe as a constant thinker and innovator, is not done. He has a vision to grow the bank to at least a ₹100,000 crore loan book in three to five years. Without taking names, he says he’s keen to be counted among his much larger peers.

The potential for growth has catapulted AU Small Finance Bank to a market capitalisation of ₹33,700 crore ($4.4 billion), with Agarwal’s 28.8 percent stake worth $1.3 billion, making him a new Indian entrant on the Forbes Billionaires List. With 6 percent of the bank owned by employees, he’s also shared his wealth and recently set up a foundation donating 25,00,000 shares worth ₹260 crore. But Agarwal, who colleagues describe as a constant thinker and innovator, is not done. He has a vision to grow the bank to at least a ₹100,000 crore loan book in three to five years. Without taking names, he says he’s keen to be counted among his much larger peers.  For starters, it didn’t have senior management approving loans. Files were sourced from auto dealers and approved at the branch level itself. It would disburse the loan and make sure it collected the registration certificate from the vehicle owner in 30 days to reflect its name as a financier. The senior management kept a watchful eye, but didn’t get into individual loan decisions.

For starters, it didn’t have senior management approving loans. Files were sourced from auto dealers and approved at the branch level itself. It would disburse the loan and make sure it collected the registration certificate from the vehicle owner in 30 days to reflect its name as a financier. The senior management kept a watchful eye, but didn’t get into individual loan decisions. In 2017 when RBI invited applications for small finance banks, AU knew a new growth window had opened up. There were three conditions to meet. First, 25 percent of branches had to be in villages with no branches. Second, half of all loans should be lesser than ₹25,00,000. And priority sector lending requirements were hiked to 75 percent instead of the 40 percent that universal banks have to meet.

In 2017 when RBI invited applications for small finance banks, AU knew a new growth window had opened up. There were three conditions to meet. First, 25 percent of branches had to be in villages with no branches. Second, half of all loans should be lesser than ₹25,00,000. And priority sector lending requirements were hiked to 75 percent instead of the 40 percent that universal banks have to meet.