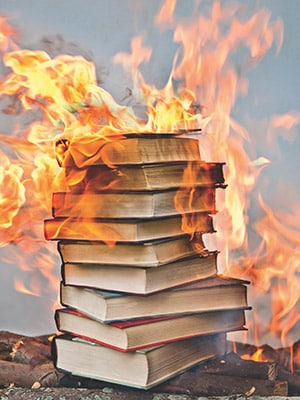

How long does the book made of paper have?

I don’t think it matters in the long run how much time paper has left. As long as content remains alive, we’re okay, says Urvashi Butalia

The one thing that can be said with certainty about the state of the publishing industry in India is that nothing can be said with any certainty. After 1972, when the government commissioned the National Centre for Applied Economic Research to do a survey of book publishing in India, there has been no systematic study, so we have no reliable stats at all.

Some people in publishing say the industry in India is valued at Rs 5,000 crore; others say Rs 7,000 crore (these are the figures most widely bandied about).

Just as no one really knows the size of the industry, no one really knows much about growth figures. Everything is based on impressions, assumptions and speculations, with some facts lying at the bottom. The general wisdom is that in trade publishing (books targeted at the mass market), growth is somewhere between 20-30 percent annually. About other sectors not much is known, although some estimates can be made for the educational sector by computing growth in education and institutes.

Growth will not stop in the near future. India is one of the few markets in the world that is not yet saturated and that still has a very low per capita book consumption. As education grows, as literacy improves, as urbanisation spreads, as incomes increase, as the media spreads, growth in books will also accompany these, although the form of the book may well change.

This is of course why all the big guns are flocking here: They see growth, growth, growth! This is borne out by what we see happening on the ground: An increase in the number of bookshops (even if some chains have shut down shops, we still have more bookshops than we had in the seventies), online selling, book festivals, more authors. We know change is happening, we just don’t know how much.

One of the interesting things about Indian publishing is the mix of old, new, independent, multinational, and multilingual. All of this may change with the big guns coming in.

What is certain: Indian readers are changing. It’s difficult to say how, but it is clear that the Indian reader is hungry for things to read and, for me, that is the beginning of a major change. They’re open to all kinds of books, which is also important.

Look at the genres jostle with each other (and working!): Autobiography, fiction, detective fiction, cookery, cricket, blogs, etc. And that’s in all languages, not just English. Plus there is so much exchange between Indian languages now. And so many literature festivals! Some of it is the copycat effect, but a lot of it comes from a genuine interest in books and more writers writing.

I think festivals are great for authors: They bring readers and authors together and nothing could be better for the craft of writing and for publishing. Also, in a country that is still not well served by bookshops, they help readers to have access to books.

If there is any caution I would put to this, it’s this: I hope more and more of our litfests keep a balance of English and Indian languages (I refuse to call them regional, it’s insulting) and sell books in those languages, and I hope more and more of them go to smaller cities and towns.

Today’s challenges have seen some in Indian publishing reacting well, seeing change for what it brings, both the good and the bad; others have fought for protectionism, tried to stop FDI, some for political reasons (and these are often suspect) and others for practical ones, or commercial ones. So many are scared of losing their markets to the big guns, but I think we have to really think on our feet about how to deal with this, and people are not doing enough of that.

The more difficult change has been the one that has come with the digital revolution. Those publishers who have taken this on board have done very well in coping with this change.

But there are others who have been suspicious, who do not know, who don’t have the wherewithal to find out, and who are confused. I’m not saying they haven’t reacted well, but that they have not reacted speedily. Perhaps because you really need to know what you’re getting into before you put your foot in. (We at Zubaan are an example of this. We’re not closed to these changes, we feel we have to implement them, but I don’t have the money to invest in finding out how to do it, so we have to learn as we go along.)

As an industry, we’re both threatened and excited by e-books. In India, I think the paper book will be around longer than in many other countries. We are still, in terms of numbers, a country of book hunger. And electronic gadgets are not so easily available or affordable, so we know that books will not disappear. But there is also the uncertainty of not knowing what exactly will happen.

I think pretty much everyone is trying to do two things: Turn their backlist and out-of-print books into e-books, and ensure that every new book is simultaneously released as an e-book. No one wants to be left behind. Some may be slower than others but everyone wants to be there.

At the moment, the e-book market is a mystery for all publishers, so they want to play safe. No one really knows how to price, and the best thing therefore is to go with the price you know. Plus—and this is a major concern—no matter how much DRM (digital rights management) you do, e-books can be, and are, hacked and accessed for free, so there are genuine copyright issues. Many publishers feel they will be soon be giving away stuff, so they want to charge while they can.

Books today can be read with sound, with music; you can witness notes, see what other people have to say. Many educational publishers say that in turning their books into e-books they are not relying on the printed version at all, or not being faithful to it; they are using the characters from the book and going much beyond. And yes, there are writers who are doing this with their books.

I think we have to realise that it is only a matter of time before the pressure for knowledge to become free and easily available will catch up with us. We have to see what we can do which can keep the publishing profession alive, and what we can do to spread knowledge.

I find Pratham’s mixed model quite fascinating, and it’s something we would like to experiment with: Ask our authors if they want their stuff to be freely available and if yes, put it out there. Or work out a staggered model: Charge for a few years and then make it free. And we have to also learn to deal with providing a smaller product—smaller, shorter books, single essays, single stories. In the way Flipkart sells a song for Rs 7, we should be able to sell a story for Rs 5 or 10.

I don’t think it matters in the long run how much time paper has left. As long as content remains alive, we’re okay. I think in all this anxiety around the paper book we forget that this wasn’t always the form of the book. The nature of content is changing rapidly, but people will always hunger for knowledge, and for as long as they can get it from books, that’s great.

(As told to Peter Griffin)

Urvashi Butalia is a publisher and writer. Co-founder of Kali for Women, India’s first feminist publishing house, and now director of Zubaan, an imprint of Kali, she writes on a range of issues, principally to do with gender. Among her published works is the award-winning oral history of Partition, The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India (winner of the Oral History Book Association Award 2001 and the Nikkei Asia Award for Culture 2003). She was awarded the Padma Shri in 2011.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)