Singur Is Still The Waste Land

Everything that could have gone wrong with industrialisation went wrong in Singur. What is now being fought in the court is simply a tussle for the moral high ground

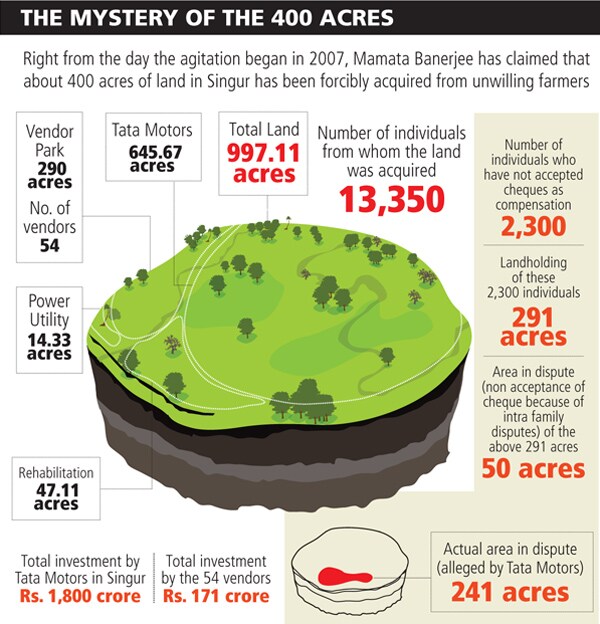

On the night of June 21, around 10 p.m., the police of West Bengal’s Hooghly district descended on Tata Motors’ half-built Singur plant and threw out the private guards there. In about half an hour, the new government in West Bengal, under the leadership of Mamata Banerjee, took over the 997 acres that had proved to be the Waterloo of the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M) and its allies.

Earlier, around 5:30 in the evening, a letter had been faxed to Prakash Telang, managing director of Tata Motors, stating that the government was reclaiming the land under the Singur Land Rehabilitation and Development Act, 2011, passed by the legislative Assembly a week earlier. The law charged Tata Motors with “non-commissioning and abandoning” of the project and went on to state that “no employment generation and socio-economic development has taken place and people in and around the area have not benefited in any manner”.

The company says it didn’t get the fax. But local Trinamool Congress (TMC) workers had pasted the notice on the boundary wall of the Singur plant. Tata Motors says four-and-a-half-hours hardly constitutes prior intimation. “Even conventional norms, decency or civility demands that you can’t do that. The notice eventually came to us only on June 28 in Mumbai,” says a senior official at Tata Motors who did not want to be named.

Although Tata Motors officially got the notice on June 28, it had learnt of the notices pasted on the Singur plant walls on the night of June 21 itself. That very night, the company got in touch with J.N. Patel, chief justice of the Calcutta High Court and pleaded for a stay, on the grounds that the state can’t take over its land. Patel said he could not pass a stay order, but would put in a request to the government. Not sure if that would work, Tata Motors went to the Calcutta High Court, contesting the constitutional validity of the Singur Act.

In the days that followed, Mamata Banerjee tried to fulfill her electoral promise of returning the land to farmers who, she insists, had been forced to sell by the previous government. At Singur, tables were put up as counters and ‘unwilling’ farmers were asked to submit details of their land holdings.

Even as all this was happening, during a hearing on June 24 in the high court, Tata Motors’ counsel requested the advocate general to maintain the status quo regarding the distribution of land. The advocate general said it was not possible for him to respond right away, but he would think about it over the weekend.

Beyond Courtroom Drama

Not sure of what the outcome would be, Ravi Kant, the non-executive vice chairman of Tata Motors, decided to intervene. On June 25, he met state Finance Minister Amit Mitra and Commerce and Industries Minister Partha Chatterjee at the Taj Bengal. At the meeting, where legal counsels of both sides were also present, Chatterjee was curious to know why Tata Motors chose Singur, knowing full well that it was one of the most fertile lands in West Bengal. Kant replied that it was not them but the former government that chose the land.

(On December 4, 2006, in response to a query from the Association for Protection of Democratic Rights under the RTI Act, the West Bengal Industrial Development Corporation [WBIDC] had said Singur was preferred for its accessibility and availability of infrastructure.)

The meeting lasted a few hours but no settlement was reached. According to sources, Tata Motors wanted a compensation of about Rs. 2,000 crore to leave Singur. For an almost bankrupt state government, this was out of the question. According to a source, Chatterjee vehemently opposed it, asking why Tata Motors wanted Rs. 500 crore more than what they had invested.

On June 27, with still no word from the advocate general, a frustrated Tata Motors knocked on the doors of the Supreme Court, requesting a stay to ensure “that the position on the ground should not be irretrievably changed when the main matters are pending before the Calcutta High Court.” Two days later, the apex court stayed the redistribution, but said the process of identifying land holdings could go on.

Meanwhile, Singur swung between hope and despair as the long-term implications of the Supreme Court’s stay trickled down to the farmers. “There is a sense of being lost in the quagmire of legality and a fear that we will not get back what we have been fighting for so long,” says Dudh Kumar Dhara, the chief of Beraberi gram panchayat and a member of the committee set up to help return the land.

The serpentine queue of farmers at the block development office thinned as they realised that the wait to get back their lands was far from over. Pulak Sarkar, the block development officer of Singur, told Forbes India on July 2, “There is a visible fall in the enthusiasm of the people, and the number of submissions has reduced drastically. Even fewer forms were submitted today.”

TMC is well aware of the repercussions of not fulfilling its pre-poll promise. “Our government is trying to do a historic act by returning the acquired land to the rightful owners. There are lot of vested interests that do not want it to happen and hence [the government] is facing opposition,” says Becharam Manna, a TMC legislator from Haripal who had been at the forefront of the protest against land acquisition.

Is The Singur Act Legal?

Tata Motors believes it has been victimised and that Mamata Banerjee is doing everything she can to sully its reputation. To begin with, the Singur Act charges Tata Motors with abandonment and non-commissioning of the project. “Everybody knows the conditions under which Tata Motors had to withdraw from Singur. It was amidst violence, threat to our personnel and property and an environment not conducive to business,” says the Tata Motors official.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

On August 22, 2008, when Tata Motors appealed for calm, it was rebuffed with a blockade of National Highway 2 and a rise in incidents of assault and intimidation of its personnel. The deadlock had continued despite several rounds of talks between the TMC, the CPI-M and Tata Motors. The company finally stopped work on the plant on October 3, 2008, and eventually moved out. “There were more than 100 FIRs filed with the police around that time. So the whole charge of abandonment and non-commissioning of the plant is based on misrepresentation of facts,” the official says.

The Singur Act, however, categorically states that since the land was allotted for a specific purpose that was not carried out, the government has a right to take it back.

Then, constitutional validity of the Act itself is in question and such a situation has never happened in India before. “The state has no power to pass the Act. This law is not in sync with the Central Land Acquisition Act,” says lawyer Mukul Rohtagi, who is representing Tata Motors in the Supreme Court. The West Bengal government, however, believes there is a precedent in Tamil Nadu in the late 1990s.

It also appears that the state’s counsels are now studying the General Clauses Act of 1898, which empowers a government to cancel and alter notifications. Under Section 21 of the Act, the authority issuing any notification can change, amend or even cancel it if it so feels, says D. Bandyopadhyay, advisor to Mamata Banerjee and architect of West Bengal’s land reforms of the 1980s, in an Economic and Political Weekly article of November 2009.

Legal experts believe the Doctrine of Primary Estoppel in law protects a private citizen from a government reneging on an agreement. “The state had promised Tata Motors the land and now Mamata is attempting to pass a law and return the land back to the farmers. In this case the doctrine operates against the government,” says Diljeet Titus, managing partner of Titus & Co., a New Delhi-based law firm.

As per the agreement, WBIDC has leased 645.11 acres in Singur to Tata Motors for 90 years. The company has been renewing this lease every year by paying Rs. 1 crore to the WBIDC. “The government cannot terminate the lease forcibly and under no circumstance can the possession of the land be taken,” says Rohtagi.

There have also been questions on what Tata Motors would now do with the land. Last September, WBIDC wrote to the company, asking what it planned to do in Singur. Tata Motors replied that it would consider moving out if the company and its vendors are adequately compensated. In fact, speaking at the annual general meeting of Tata Tea in September 2009, Ratan Tata told the media, “If they compensate the total investment we put into the land, we may return it. Right now there are no plans regarding the Singur land but we don’t wish to sit on it.”

More Complications

Meanwhile, Tata Motors’ vendors, who were watching the drama unfold from the sidelines, are getting into the ring. “We had been waiting to know about Tata’s plan and we are coordinating with them. Now many of us are going to court,” says Surinder Kapur, managing director of Sona Koyo, a Tata Motors vendor. Their case is slightly weaker than the Tatas’ because they do not yet have a firm lease. Fifty-four vendors were to set up their units near the mother plant; 13 had already begun construction and have collectively invested about Rs. 171 crore so far. They would be reluctant to get out without a compensation.

Mamata Banerjee had earlier promised farmers that they would get back the same land they had given up. But there is not much they will be able to do with it. As things stand, of the 997 acres, only about 70 acres are cultivable. The damage from fly ash (used as landfill), cement and construction materials is so great that huge investments are required to make the land cultivable again. “Common sense suggests that this land can’t be used for cultivating crops and vegetables again. I don’t see the point in all this,” adds Kapur.

West Bengal’s loss has been Gujarat’s gain. Singur was supposed to create 2,000 direct and about 10,000 indirect jobs. In the Sanand Nano plant, out of the 2,700 people in operations, 1,700 are from Gujarat. Out of 1,000 managers at the plant, 300 are from the home state. Now that the Singur issue is in court, it could be a long time before things change on the ground. There won’t be any land or jobs.

“This is a matter that should not have gone to the courts. For that you need to talk… What’s so difficult?” asks Tatas’ counsel Rohtagi.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)