Patel Engineering Moves Beyond the Known Horizon

Patel Engineering de-risks its government contract business with plans for power generation and real estate development

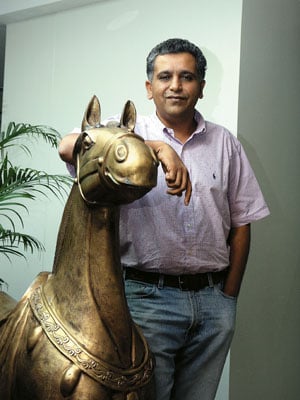

There are unmistakable signs of a cozy family business written all over the Rs. 2,838 crore Patel Engineering (PEL) headquarters in Goregaon, a Mumbai suburb. Rupen Patel, the managing director, saunters along in crumpled denims; executives drop in unannounced at his office. For lunch, he and his sister Sonal Patel, an executive director, order food from the local restaurant. Sonal has soup from a cheap-looking bowl and polishes off what looks like a more presentable version of the sandwiches you get in Mumbai roadside kiosks.

There’s nothing that gives away the serious nature of the business that PEL does. More so, there is no evidence of the dilemma it has faced in recent times. PEL makes most of its money from building dams and hydroelectric power plants and boring several kilometres of small tunnels through densely populated cities. A growing incidence of problems associated with environmental clearances and public outcry against large dams in general is making life difficult for the company. After six decades in business, the family is grappling with some fundamental questions.

This far, the Patel family largely stuck to a conservative approach of being contractors for projects funded by governments and institutions like the World Bank. Rupen Patel’s father and the current chairman Pravin Patel — who still comes to work every day — thought diversifications were unnecessary when the contract business was so good. Rupen Patel, the third generation member of the enterprise, too thought he would largely stick to the knitting. He bought some small businesses including a micro-tunneling company in the US some years ago, but never strayed far from the company’s core competence. He, in fact, still nurtures big ambitions in dam construction. “I want to be the finest dam builder around.”

So when the younger Patel suggested to the board about 18 months ago that the company start new lines of businesses such as power and real estate, there were quite a few questions. India is just now beginning to build infrastructure in a serious way and is expected to spend billions over the next decade. Wouldn’t it be a good idea to aim at being a large player in this business? Why should capital be employed in new businesses, particularly when the elder Patel abhors paying any kind of interest?

Rupen Patel’s plan was to run large hydroelectric power plants and start selling apartments and office space. He argued his case saying that the company had the expertise of building both power plants and civil constructions for others and could easily do it for itself. Says K. Kannan, ex-chairman of Bank of Baroda and an independent director on the PEL’s board: “Rupen clearly was the next generation and wanted to grow a little faster.”

Despite being one of the most profitable exchange-listed infrastructure companies, PEL has been a laggard in growing big. Companies like Hyderabad-based Nagarjuna Construction and IVRCL and Delhi-based Jaiprakash Industries have grown much larger building projects that PEL was also skilled at (though not dams). They have also created much more shareholder value by leveraging the same set of engineering skills.

“Going beyond just infrastructure contracts is the next phase of evolution,” says Patel. He had better be right. Kannan says the senior Patel is still very careful about how much each of his family members makes from the company. Though directors can get up to 10 percent of the disbursable profits as bonus, Rupen Patel at best gets 4 percent, thanks to his father’s philosophy. Says Kannan: “Pravinbhai monitors performance very closely.”

Still it is with the help of the likes of Kannan and the other independent directors that Patel got his way to put money in the new businesses. But, before that he had to make an elaborate presentation to the board members about his case.

There were several things that worked in Patel’s favour. Five years ago, when scouting around for new growth avenues within its areas of expertise, the company acquired two companies in the US. Both the firms gave it access to new technologies in areas of reinforced cement concrete (RCC) structure and in micro-tunnelling. At that time, Sonal Patel argued that the US companies will give them access to the local market as Indian firms would never be allowed to build dams there. “We were looking for ways of moving away from run-of-the-mill jobs,” she says.

The Patel siblings pulled it off. They won a series of dam orders abroad. They have completed a reconstruction project for one of the largest RCC reservoir dams in the US and are finalising contracts for two dam projects in Australia. The micro-tunnelling business has also grown. In Mumbai, for instance, PEL helped the municipal corporation build water and sewage pipelines beneath roads without having to cut them. Today, PEL has cornered all such projects of the municipality worth more that Rs. 300 crore. These successes have made their father bet on their instinct for a larger play in entirely new areas.

There was another reason for diversification. While infrastructure is a big money game, it is also bound to be delayed at every stage from tendering to environmental clearance to construction. For instance, a PEL irrigation project in Andhra Pradesh has now been stuck of over 18 months, without any resolution in sight. The senior Patel was getting a bit tired of such delays. He began to think that the business was becoming unpredictable and there was a need to deploy cash in more predictable businesses.

Having established his case for diversification, Patel still claims to be conservative in his approach. He will build two power plants — one hydro and one thermal — to secure income from their own assets. But, will he make enough money a few years down the line when the power plants of several biggies like Reliance, L&T and Jindal also go on stream?

Patel does believe that eventually thermal power will become a commodity and may not be very profitable in the long run. Despite that PEL decided to set up a thermal power plant, as Patel managed to pick up a few coal mines cheaply while working on infrastructure projects in Africa and Indonesia. Since there is no alternative to thermal power during peak hours, especially in cities, Patel believes that he can be competitive as he has already fixed his input costs.

The 1,200-megawatt thermal power plant will come up in Nagapattinam in Tamil Nadu and all clearances, including the environmental one, are in place. The smaller 120 MW hydro power plant will come up in Arunachal Pradesh. Patel doesn’t expect any trouble in selling hydroelectric power, as it is always cheaper than power from other sources. PEL’s investment outlay for both projects is Rs. 7.000 crore with a 30 percent equity component.

His other bet, in real estate, mirrors the strategy other infrastructure companies too have adopted in the recent past. Hindustan Construction Company (HCC), predominantly a construction contractor, is developing its own elite township Lavasa, 100-odd kilometres away from Mumbai. Jaiprakash Associates is also building large scale housing projects in Noida. Analysts expect that these companies will hugely benefit in valuations on account of these diversifications. In a recent report on HCC by Mumbai-based Elara Securities, analyst Abhinav Bhandari says he expects the valuation from the real estate business to be more than that of the contracting business.

The risk is minimal in his real estate projects, argues Patel, as his land comes at a historical cost. Two decades ago, PEL had acquired land in the outskirts of Bangalore, while constructing a road project. Eventually, as Bangalore grew, PEL’s land bank fell close to the electronic city where many software companies have built their offices. Says Patel: “I have 100 million square feet of land at a cost Rs. 40. Even a tile is more expensive.”

To start with, Patel is building affordable tenements aimed at the very ‘mobile’ software professionals in Bangalore. He is also building an office complex adjacent to PEL’s corporate office, which would be let out on long leases.

The company also has a land parcel opposite the new airport in Hyderabad. Patel recalls that the company got the land by a stroke of luck, when one day all the government surveyors vanished from a road project they were building near Hyderabad. When Patel found out that they had gone to survey land for the new airport, he moved in quickly and bought some land. Says Gopal Ritolia, research analyst at India Infoline, a Mumbai-based broking firm: “In the next couple of years, real estate will contribute a great deal to PEL’s bottom line.”

Patel says that without any diversification, the company’s revenue would go up to Rs. 8,000-10,000 crore in the next five years. Once the power plants and real estate projects go full steam ahead, he expects his turnover to increase to Rs. 15,000 crore. His contracting business by then would be Rs. 7,000 crore, power would bring in Rs. 3,000 crore, real estate about Rs. 1,500 crore and the balance would come from mines. “We are talking of a different dimension here. Are you with me?” asks Patel.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)