Indian Steel Companies May Unite for Cause

Indian steel companies are pondering whether to put aside their rivalry and bid together for one of the world's most precious iron ore reserves in Afghanistan

For a millennium and a half until 2001, the giant Buddhas of Bamiyan in central Afghanistan were witness to much history. They overlooked the passing of the trade caravans of Europeans, Indians and Chinese along the Silk Route. Over the centuries, the Gandharas, Hunas, Ghengis Khan and even Soviet tanks had left their imprints in the vicinity. Throughout all this turbulence, the statues stood unchangingly as the symbol of Buddha’s greatest teachings — harmony and co-existence. So, when the Taliban dynamited and destroyed the Buddhas a decade ago, it appeared as if these ideals had been lost forever.

Today, the Bamiyan Valley is helping to rediscover a new future for Afghanistan. Not only is there an international effort to rebuild the Buddhas, there is also a plan taking shape to convert the Bamiyan province into a thriving industrial centre. Not far from the ruins lies a hidden treasure: The 1.8 billion tonne Hajigak iron ore mines. With a very high ferrous content of 68 percent, these are among the most coveted reserves in this part of the world and represent the best chance for rebuilding the war-torn nation.

This January, the Hamid Karzai government put the exploration rights to the mine up for an open bid. It attracted some of the biggest mining and steel firms from around the world, including Vale of Brazil and China Metallurgical Group. But the biggest interest came from Indians. Fifteen of the 22 firms that expressed an interest in tapping the mines are Indian. If all goes well at the final opening of bids in August, India hopes to use the Hajigak mines as a gateway to playing a role in Afghanistan’s transformation.

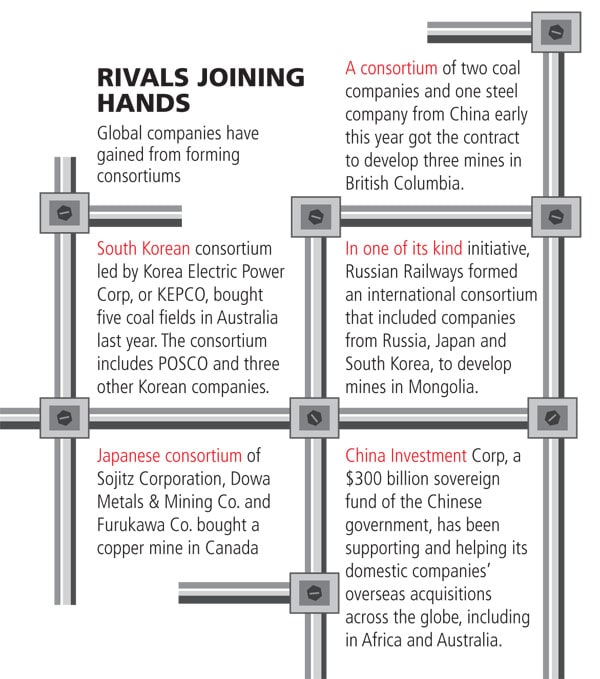

But the Indians face a dilemma. If each of the 15 firms competes on its own, the flock could be swept aside by the global giants. So, the Indian companies have done something they never did before: They have taken a leaf from Buddha’s teaching of peaceful co-existence and are exploring the possibility of bidding as a single consortium. Now, these are hardwired rivals competing for the $51 billion steel market back home. If they decide to bid together, they would be opening a whole new chapter of co-operation.

Understandably, the Indian government is delighted. It has backed the plan with a promise to fund 15 percent of the acquisition corpus. In early April, the Indian Express reported that at a high level meeting chaired by steel secretary P.K. Misra, senior officials from the ministry of external affairs said the government had the provision to dip into the Rs. 5,850 crore corpus set aside for executing developmental projects in Afghanistan. When asked, Misra downplays the development saying that no final decision has been taken. Given that some of the companies trying to get into the joint bid are state-owned, the final go-ahead will, of course, have to come from the finance ministry.

The joint bid is seen as a stepping stone to a larger objective: The creation of India’s own sovereign fund that will help home-grown companies buy expensive resources abroad and also help meet the country’s energy needs. For it is not only steel companies looking to buy mines abroad, but also power generation players hungry for coal mines. “Various concepts including a sovereign fund are there, but all are in debating stage right now. A sovereign fund will come under the MoF and it has to decide on that,” says Misra.

Bonds of Steel

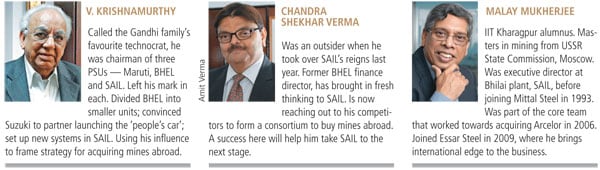

Three men are the centre of this initiative to bring together rivals for a greater common purpose. V. Krishnamurthy, former chairman of Steel Authority of India and now the head of the National Manufacturing Commission, C.S. Verma, the current SAIL chairman and Malay Mukherjee, CEO of Essar Steel who had earlier worked at both SAIL and ArcelorMittal. They think the urgency for the steel industry to collaborate hasn’t come a day sooner.

Indian steel companies are ravenous for iron ore to feed an economy growing at 9 percent. But “the Indian steel industry’s current plans [to secure raw material] are not working,” says Mukherjee. And without the security of getting raw material, the future plans of the Indian steel industry could be in jeopardy.

The industry veterans say that a joint bid in Afghanistan will work like a pilot project for Indian companies to co-operate in matters like global sourcing of raw materials and expanding the market for steel. “If this arrangement for the Afghanistan bid works out, it will help us expand its scope in many more ways,” says Verma.

While NMDC, India’s largest iron ore miner, will lead the Indian consortium, the partners will get the allocation of resources as per the investment they bring. It looks like the NMDC consortium will include SAIL, Tata Steel, JSW and Essar. This is pretty much most of the industry anyway.

There have been both short-term and long-term triggers for Indian steel companies to come together. We are living in an era of rising commodity prices. In just over a month, spot prices of key raw materials like iron ore and coking coal have shot up by 30 percent.

Indian firms have also struggled to buy mines across the globe. Tata Steel and JSW Steel have lost out on iron ore mines in Africa, while SAIL has struggled to match the speed and bidding power of its international peers while evaluating coal mines in Indonesia and Australia.

What’s more, as the price of raw materials has climbed, companies have been forced to move from annual long term contracts to the now quarterly, or in some cases, even monthly contracts where prices are closely linked to the volatile spot rates. This has not only increased the scramble among companies to buy mines but also pushed up the value of these mineral resources.

In India, SAIL and Tata Steel have iron ore mines, unlike others. But when it comes to coking coal, even they are not self-reliant. In the case of Tata Steel, the need is more urgent to feed its plants in Europe that it got through the Corus acquisition in 2007. None of these plants owns mines.

SAIL, despite its iron ore cushion, saw its net profit drop by 34 percent in the third quarter of 2010-11 due to high coking coal prices. “Even our next phase of expansion, which will see SAIL’s annual capacity increasing to 24 million tonnes from the present 14 million tonnes, would be unviable unless we have access to more captive mines,” says Verma.

United, We Bargain

Verma and Essar Steel’s Mukherjee have been the most vocal backers of the new initiative. Mukherjee is a former SAIL veteran who later became part of the core team of L.N. Mittal. Back in India since 2009, Mukherjee has become some sort of a champion for co-opetition. He points to international examples such as Mexico, where ArcelorMittal shares an iron ore mine with a competitor. “Resources are divided according to investment and production history,” says Mukherjee, who adds that Indian companies have already lost an opportunity in Mongolia. The central Asian country had earlier this year invited companies to develop the world’s largest untapped coking coal deposits. Consortiums from China, Russia and South Korea have made bids. There was none from India.

Verma cites another international example that could help broaden the scope of the Indian initiative. “Japanese steel mills every year jointly bargain with mining companies for annual contracts to procure raw materials. Indian companies should also come together to increase their bargaining power and thus get better rates,” says Verma. His office is now in talks with heads of other steel companies such as JSW Steel and Essar Steel who also import coking coal. Together, steel companies in India import about 40 million tonnes of coking coal a year, enough to give them bargaining power. (SAIL is also in talks with an undisclosed India private company to jointly buy a stake in Indonesian mines.)

The other area where a consortium could work is opening up new market segments within India. Take the household sector or the farming sector, for instance. It may not be viable for one firm to seed these markets as initial volumes will not justify product development and marketing costs.

Interestingly, that was a task that Indian Steel Alliance, or ISA, was supposed to do. Set up in 2001, ISA had five of the biggest Indian steelmakers as members — SAIL, Tata Steel, JSW Steel, Essar Steel and Ispat Industries. “It was set up as an industry representative at government level and also internationally. Unfortunately, differences between its members saw it shutting shop in 2008,” says D.A. Chandekar, editor and CEO of SteelWorld, an industry information and consultancy organisation.

The bone of contention, say industry executives, was setting the monthly prices of steel products. “While in the beginning the system worked, later on government pressure would force either SAIL or Tata Steel to take back the hike. Other companies were forced to follow. Differences cropped up,” says a former executive at one of the private steel companies. From 2004, when the rise of the Chinese steel industry pushed up raw material prices and made mines integral for steel business, the differences widened. “As SAIL and Tata Steel already had their own iron ore mines, other companies wanted preference in allotment of mines,” says the executive. In 2007, Tata Steel withdrew from the Alliance and SAIL followed suit a year later. ISA soon folded up.

It was a sad end to the first of its kind public-private partnership in the steel industry. Verma concedes the Afghanistan initiative to revive that idea is indeed a difficult task.

There are sceptics to the plan too. J.J. Irani, the former managing director of Tata Steel and ex-chairman of ISA told Forbes India in an email that “I do not think there is any potential” in the activity. While he declined to explain, old timers say it will take a “great level of maturity” on the behalf of the players to “leave their egos behind”. Most of these companies have locked horns over Indian mines, especially the Chiria iron ore mines in Jharkhand where SAIL has taken claim. “Also, can the decision-making mechanism of a public sector company like SAIL synchronise itself with that of a private company like Tata Steel?” asks a senior executive at one of the private steel companies. Forbes India sent emails to Tata Steel and JSW Steel asking if they are part of this new initiative. Neither of them responded.

For India, Afghanistan is a strategic priority. It enjoys immense goodwill among Afghans that the US hasn’t been able to garner even after investing $50 billion. The country has been a theater for war for too long and when the tide turns, there will be great business opportunities. For India to maximise its role in rebuilding Afghanistan, the synergy of private and public sector companies is crucial.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)