Indian Auto Majors Look Skywards

Unlike global auto majors who have typically steered clear of the big aero dream, the Tata group and Mahindra & Mahindra are looking to ambitiously breach the road-air divide

In 2011, when the Tata-Sikorsky joint venture started making components at its Hyderabad facility, Tata veterans were confident the process could not be too dissimilar from that in their other plants. They were about to learn otherwise. Because what they saw threw them. Completely. Documentation papers for a 2 mm part often added up to 2-inch-thick dockets. Compliance certification could go back to the origin of the metal (aluminium)—which mine it had originated in, which mill it came from, which broker it was bought from.

This level of detailing can be attributed to the industry’s famously low tolerance for error: One of the ways in which this is enforced is through a detailed trail of every manufacturing activity. Each part has to be traceable and all processes must be certified.

More recently, in Bangalore, the folks at Mahindra & Mahindra (M&M), too, recognised that the aerostructures facility they were building was going to need considerably different planning. “We tweaked the plant layout,” says Arvind Mehra, CEO, Mahindra Aerospace. “We’ve built it so that there is more space to store our manuals than there is for our computers.”

Aerospace manufacturing, India’s two largest and most globalised carmakers were fast learning, was literally on another plane.

***

They—and we—can be forgiven for assuming that the automotive and aircraft manufacturing industries have enough in common to suggest an ease of transition. The dynamics are similar enough: Both are cyclical businesses whose struggles with managing demand, production and workforce are regularly chronicled. Yet, in the hundred years that both the industries have existed globally, few carmakers have started making planes. Aerospace has remained a specialised industry with a handful of global players; it is rare for an auto group to have tried its hands at it.

Most aerospace products are highly engineered, far more than automobiles—they are also high- value-add and low-volume products. However, the biggest inhibitor is the huge capital investment needed to become a major player—either an OEM or Tier 1 manufacturer. An entrant would require a large appetite to invest billions of dollars, as also substantial patience to handle the long payback periods. It is no surprise that Airbus and Boeing, the two largest players, still rely heavily on their respective governments. The journey may be less expensive, but it is equally risky for small plane makers.

A famous exception, which was in the news recently for making the auto-to-aero journey, is Japanese car and motorcycle maker Honda Motor Company. After almost three decades of planning and research, HondaJet has started building a small, light but strikingly beautiful aircraft, with two over-the-wing engines. The plane is being built in the US and expects to get its certification this year. Honda reportedly has a hundred orders for it. Commercial success, though, is still far from proven.

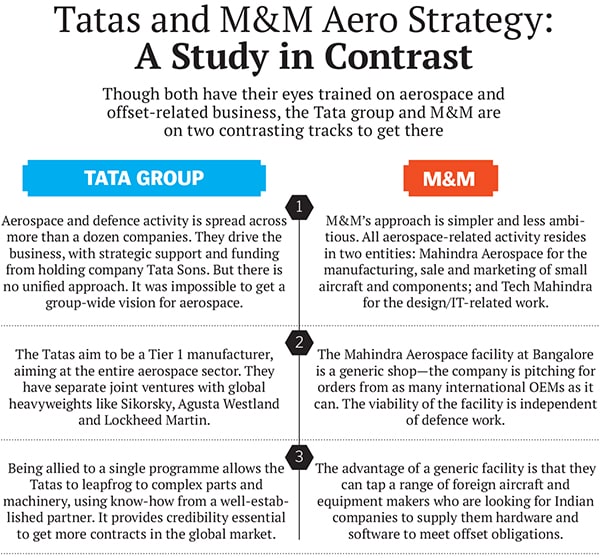

Against this global backdrop, the story in India seems to be evolving along a different trajectory. Two of the country’s strongest auto-makers have ventured into the production of planes, aero structures and components. Starting almost from scratch about six years ago, about a dozen companies from the Tata group and the aerospace arm of M&M have been—separately—building their competence. Activity is now picking up and is straddling the gamut, from producing large parts such as the fuselage (chassis) and empennage (tail section) to design, technology and electronics. The vision is tinted with ambition as both have their eyes set on the whole shebang, right from the design to the manufacture of airplanes.

The build-up has involved acquiring foreign companies with expertise and forging JVs to contract-manufacture for big-name global partners. Both have used their auto-manufacturing expertise to launch them into civil and defence aerospace.

It is expected that 2014-15 could be the tipping point. Between Mahindra’s small aircraft sales and components business, the company is looking to touch revenues of $300 million in 3 to 4 years. The Tatas are more advanced, with at least three manufacturing facilities certified and producing components, and more on the anvil. Most of these firms are unlisted, and financial details are unavailable.

Success is a function of capability and scale and, by international measure, both are still at Tier 2 or 3 levels. But (if plans are not disrupted, and they are supported by decisive changes in regulations) they could well be on the cusp of bigger things.

From Jeeps to Gipps

M&M’s aero tale has a clear beginning. It is one that Hemant Luthra, president of Mahindra Systech, the group’s component division that includes Mahindra Aerospace, loves to recount. “Back in 2007, we were doing the $25 per hour kind of work for HAL [Hindustan Aeronautics Limited],” he says. That was about to change. One of the acquisitions that M&M made at the time was Plexion, a Bangalore-based engineering company. Plexion was in a JV with NAL (National Aeronautical Laboratories) to build a five-seater plane. The Mahindras inherited this project. The notion had potential and Luthra’s group commissioned studies to verify if this could indeed take on the scale it promised.

Remember, it was a time of great buoyancy for the group—they had tasted success with SUVs, had just launched a passenger car and were acquiring component companies in Europe. The research was positive and “we soon figured out that the key is to make and sell low-cost planes that can carry passengers and cargo all over India,” says Luthra. They would need aircraft that was non-fussy, that could take off and land on short, grassy runways, be easy to maintain and not very expensive to buy.

Despite the financial meltdown of 2008, Luthra and his team succeeded in getting M&M boss Anand Mahindra excited about the idea. It was a long term bet, and one that would depend on the government liberalising rules. There was little clarity on returns, but the board gave it the go-ahead. Mahindra has often been questioned about the viability of his plan, especially with the lack of aviation infrastructure in India. His response: “When we started building jeeps decades ago, our tagline was ‘Roads will follow’. Now with aircraft we are saying runways will follow.”

However, there are several hurdles to cross before he can get there—the most immediate is the DGCA rule that prohibits single-engine planes from carrying more than five people. The GA8 Airvan is sold the world over for use as an eight-seater. Efforts to get the government to change the regulations has been a slow process.

The bigger problem that inhibits the use of small planes in India is the lack of runways and the red tape around flight-clearances. Big airports are clogged and expensive to operate from.

On the back of their leader’s confidence, five years on, M&M’s aero strategy has grown three prongs.

The first is to produce inexpensive but reliable turbo-props and piston-engine planes. “We chose to go with metal planes—rather than composites—which would be easy to sell and maintain. The focus is on building two- to 20-seater planes,” says Mehra of Mahindra Aerospace. In an interview with Forbes India in September 2013, Anand Mahindra had said that though it may not be evident yet, M&M’s aerospace foray is ultimately aimed at the Indian mass market. It fits in with the group’s plans to focus on consumer-facing businesses. “We could have hundreds of these planes flying around,” he said. The group has invested close to Rs 1,000 crore to build Mahindra Aerospace. Mehra says the advantage of an automotive background is that promoters understand the importance of investing in manufacturing and appreciate the cyclicality of business.

M&M also made a series of acquisitions and forged partnerships. It picked up majority stakes in three Australian companies—general aviation manufacturer GippsAero, component and assemblies company Aerostaff, and a Boeing Aerostructures factory that was shutting down. The deals brought three planes into the company’s portfolio: The two-seater GA2, eight-seater Airvan GA8, and 18-seater Airvan GA18. These joined the CNM5, a five-seater plane being produced in Australia.

GippsAero, based in Victoria, Australia, makes about 40 planes every year. The numbers are expected to scale up substantially once the planes begin selling in India. Mahindra’s vision: To build Scorpios for the sky. Business has been on a rebound since the Airvan was positioned as a surveillance aircraft by installing high-res cameras and equipment. “Aircraft have been sold in North America in this role and business is just opening up,” says Mehra.

The second prong of the strategy is component manufacturing. Here M&M has signed up with Spanish aero-part maker Aernnova for a technology partnership. With revenues of over $1 billion, and factories around the world, Aernnova specialises in the design and manufacture of major airframe assemblies and is a supplier of aircraft programmes for global aircraft OEMs.

Last November, M&M inaugurated a manufacturing facility near Bangalore. The group has invested about Rs 150 crore in it, and hopes that component manufacturing will yield up to Rs 250 crore. Initial business is expected to come from GippsAero in Australia.

Since the aerospace business is all about processes and controls, OEMs cannot place orders without proper certification for the operations. “We have begun pre-production trials. And hope to have the two key certifications, AS9100 and Nadcap, by the middle of the year,” says Mehra. Aernnova will eventually pick up a 24 percent stake in the Bangalore facility.

Mehra says the plan is to start with sub-contracts for Aernnova and slowly build competence to be able to supply directly to the big OEMs. Reason: Large OEMs are sticklers for quality and are unwilling to trust rookie part-makers unless they are backed by more proven players. The progression is likely to be from components to sub-assemblies and finally to structures and the whole aircraft.

Mahindra says he hopes to start building the entire aircraft in India in two years. For Aernnova, the benefits are clear. M&M is able to reliably supply cheaper parts in many other places of the world. This will provide the Spanish company a competitive edge while bidding for contracts.

The third aspect of the strategy is in the IT and design parts of the business—this gets manifested in Tech Mahindra. About 1,000 engineers are in the company’s aerospace practice do design work for marquee names such as Bombardier and Airbus. Tech Mahindra and Mahindra Aerospace have begun pitching for business together, usually for re-design work on old programmes. Mehra says his dream is to be able to make a ‘design and build’ offer for an entire aircraft.

For M&M, revenues from aircraft sales and components are currently equal. However, this can change if the company makes a big acquisition in either field. 2014, in any case, is bound to get exciting as the five-seater plane, CNM5, will be certified later this year. This will be India’s first home-built plane in the private sector.

The Tata Flight

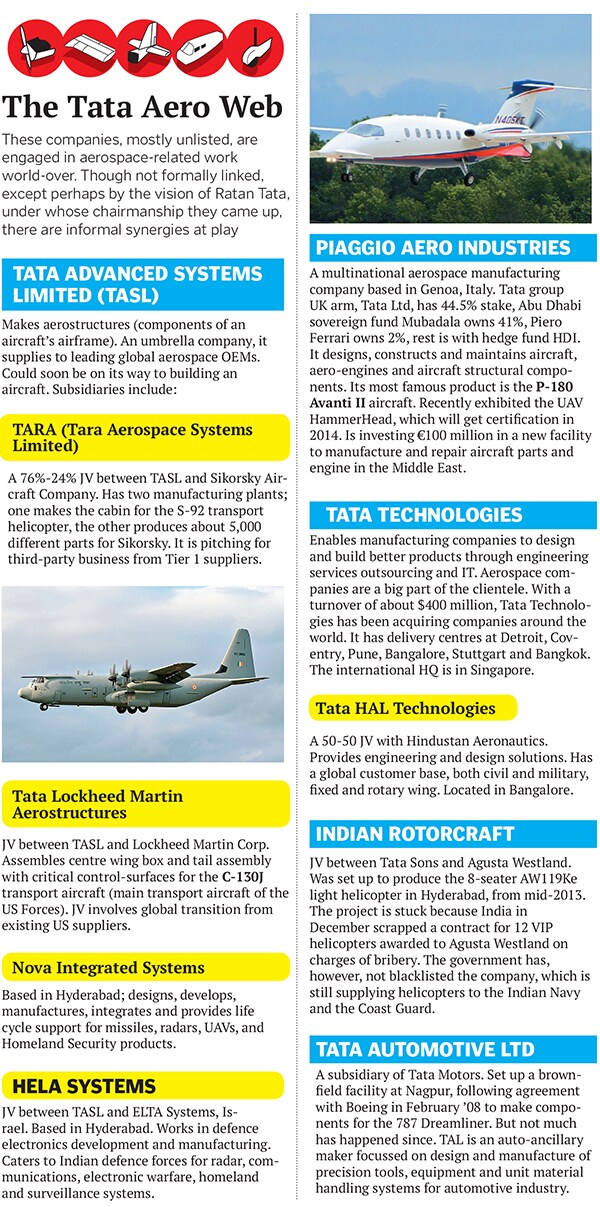

Deep in the Brazilian offshore, oil-workers file into a helicopter cabin of a large twin-enginned machine that is waiting to fly them back to the mainland. The 12.5-tonne chopper is American, a Sikorsky S-92, owned by Lider Avicao, Brazil’s largest helicopter charter company. Few of the workers using it know that the cabin, and the approximately 5,000 components that go into it, were built and, in fact, customised for Lider by Tata Aerospace Systems Limited (TASL) in Hyderabad. Sikorsky has sold about 200 of these helicopters to customers around the world and more than 50 of these have cabins made by the Tatas in India. As production ramps up (from two ship sets a month to three), half the S-92 manufacturing will be done here in the country.

In fact, TASL is now the ‘design authority’ for the S-92. This means any changes or modifications needed in the machine, based on customer feedback to Sikorsky from around the world, will be carried out in India. The two Tata companies, one to assemble the cabin and the other, TARA, that makes components (see page 65), employ about 1,000 people in all. Their facilities were built from scratch in four years.

In 2013, global aerospace production was worth $160 billion, according to data from Virginia-based consulting firm ICF International. Aero-structures form the largest chunk of this, with more than a quarter of the pie. The Tatas have been trying to get a share of this market, building capabilities in materials, machining, tooling and heat/chemical processing in their companies. “Before they stepped in, the S-92 helicopter was being built by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) in Japan,’’ says Air Vice Marshal (retd) Arvind Walia, who heads Sikorsky’s operations in India. MHI has been developing and manufacturing key components, such as wings and fuselages, for civil aircraft for several years. In 2008, MHI launched subsidiary Mitsubishi Aircraft Corporation to build the 70- to 80-seater Mitsubishi Regional Jet. The aircraft will be Japan’s first ever homegrown commercial passenger jet.

The aero adventure which started in the early 2000s for the Tatas has picked up pace but how far can they go? For instance, will they ever make the entire helicopter for Sikorsky? The Indian company certainly has the advantage of lean manufacturing, and the ability to harness significant cost advantages. Aero-structures are the largest and easiest part of the chain; other activities such as avionics and aircraft engines are far more complex. As far as Sikorsky is concerned, the Tata JV is an entry point into a huge, underserved market. The helicopter company, a division of the $60 billion giant UTC, is looking at selling its machines for both civil and defence needs. They have no orders from India yet.

Shane Eddy, senior vice president for operations at Sikorsky, is responsible for quality, supply management, assembly and flight operations in the 75-year-old company. His job includes managing supplies from production sites in Connecticut, Alabama, Florida, Poland, Turkey and India. Speaking to Forbes India in Hyderabad, he says developing local supply chains in key markets is a key part of Sikorsky’s strategy. “For large global manufacturers, it is no longer about finding the lowest-cost base to manufacture parts. Market access is a key factor,” he says. And Sikorsky is developing a relationship in India ahead of market growth. On the military front, they are preparing to pitch for contracts worth $14-$15 billion, in the next two-three years.

But, Eddy admits, “There is a limit to how far we can go. Our supply chain in India is now forward-leaning relative to the market.” Sikorsky offers helicopters for a range of applications in offshore oil, emergency response, defence and homeland security, and Eddy hopes to have the orders rolling in soon.

There is another big constraint: The Indian government’s policy on foreign direct investment (FDI). Dr Vivek Saxena is a senior consultant at ICF International, a US-based consultancy that specialises in advising companies on manufacturing. He says, “OEMs are allowed to take only upto a 26 percent stake, and this obviously limits the IP (intellectual property) they are willing to share. Indian companies can truly benefit from foreign majors only if the government allows them to pick up larger stakes. OEMs are reluctant to partner Indian companies for really high-tech work. The sector could really get going if higher FDI is allowed.”

Despite the odds, what has been a massive plus for the Tata group is its network. Which is why at TASL, while the technology came from Sikorsky, the Tata group played a critical role too. The production ramp-up was steep, and Tata veterans including Prakash Telang, former managing director at Tata Motors, were involved in looking for ways to optimise the project. The challenge was to increase production of cabins from 3 to 27 a year by the end of 2013. The JV needed support in terms of planning operations as well as on sourcing. Total Operations Planning, an optimisation process used in various Tata companies, was implemented to reduce cycle time. This involved batching of parts, and finding ways to work in parallel. Group resources were utilised while looking for suppliers: Some of these were vendors who had worked on the Indica and Nano projects.

Tata HAL Technologies, a JV with defence PSU HAL, is working on a similar project to optimise the manufacturing of the Tejas fighter (an LCA). HAL has just begun serial production and will need to ramp up from 8 planes a year to 16 in three years. As Tata Technologies COO Samir Yajnik points out, their expertise is in helping other manufacturing firms improve efficiencies.

A Global Lesson

Compared to other companies, even those in emerging economies, the two Indian companies are still in the early stages of the aerospace business. But globally, there are enough lessons to draw from companies that have developed from naught in less than a decade. In Turkey, Alp Aviation and Kalekalip are two great examples of how the Turkish are exploiting labour arbitrage, offsets and government funding to get into high-end aerospace manufacturing. Incidentally, Alp was originally an edible oil company while Kalekalip was involved in construction.

Alp is now the third largest Turkish defence exporter. At the Paris airshow last year, engine maker Pratt & Whitney awarded manufacturing work for critical components of the Joint Strike Fighter’s (JSF) F135 engine system to Alp Aviation and Kalekalip.

In China, state-owned AVIC (Aviation Industry Corporation of China), a consortium of aerospace manufacturers, has spearheaded an aggressive drive to seek foreign partnerships and offset opportunities. “China is at least a decade ahead, just look at the growing AVIC companies in both the airframe and the engine space,’’ says Saxena. Boeing and Airbus have equipped almost all their civil aircraft with components made in China, while Chinese-made aircraft have been exported to 40 countries. Airbus has cooperated with Chinese companies in all aspects from design to production and assembly.

China also produces the entire wing of the A320. It is the second country after Britain capable of this task. In 2010, the AVIC began working with Canada’s Bombardier to design, manufacture and sell aircraft together. In 2011, it formed a partnership with GE to build an avionics company.

On a wing and a prayer

“One critical difference between us and them is lack of clear government support and policy direction,’’ says Amber Dubey, partner and head of aviation at KPMG. “We need to enhance the impractical 26 percent FDI limit for global OEMs to at least 74 percent.” A low FDI limit prevents global OEMs from considering India a global supply hub. Local sourcing is limited to specific requirements of their offset obligations after they bag an order. Sensitive sectors like telecom and banking have much higher FDI limits, he says.

“Though Turkey is a democracy, much of the progress has been because of clear policies,” he points out. “Foreign companies can own up to 49 percent in the JV.” Not surprising, companies have moved forward to do more complex and lucrative work, he adds. Also, the Turkish government offers zero-interest loans to companies in the aerospace industry.

In India, manufacturers are struggling to work with the DGCA for certification. The Mahindra 5-seater plane, for instance, had to be certified in Australia, because the DGCA did not have the capability to certify it.

Other Indian companies like Reliance Industries (RIL), Godrej Industries, Ashok Leyland and Larsen & Toubro have taken tentative steps into aerospace manufacturing. India’s biggest private sector major RIL has signed up with French company Dassault to build wings for the Rafale. The aircraft was selected by the IAF for its next-generation fighter needs. But the $10 billion contract is yet to be signed. RIL is hoping to jump straight into the game despite having manufacturing experience only in the petrochemical business.

Though the business case is there for all to see, Indian companies have not gone the whole nine yards with investments. This can happen when offsets are linked to domestic manufacturing. A clear government policy that says a certain percentage of a foreign vendor’s offset obligation should compulsorily be met through investments in local manufacturing could lead to billions of dollars of investments. But even after several revisions to the defence procurement policy later, there is no evidence of any such benefit to Indian industry. For first movers, the Tatas and Mahindras, progress has been not because, but despite, the government.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)