Independents' Day: Private Equity Entrepreneurs

The entrepreneurial bug has bitten private equity veterans again. And this time, the environment may just be right

Ajay Relan is the kind of man who’s rarely rushed for words. You know, the kind of man who’s been there, done that. Until 2008, he managed Citigroup’s private equity operations (CVCI), where he built a great team and a great track record.

After he quit, he built yet another solid team and raised a $500 million fund called CX Partners, the largest first-time fund by an Indian.

But that’s not how he behaved two months ago, when a young investment banker in New Delhi spoke to him of a young consumer products company growing at unheard-of rates and seeking Rs. 500 crore in funding.

“I’m so excited I can feel my hands shaking,” he said then.

That wasn’t the Relan this young man knew. So, in his head, he dismissed the exuberance as signs of first level interest, and nothing more.

Imagine the investment banker’s surprise then when two days later a team of professionals from Relan’s fund went across to meet the entrepreneur he had talked about; not just that, they were actually discussing the broad contours of the deal.

A couple of days later, Relan invited the entrepreneur and his management team to meet up with his investment committee. Two days after that meeting, a term sheet was ready and all the stunned entrepreneur had to do was sign and accept.

The entire process took less than ten days.

Now, while CVCI under him was very quick, he would have still taken at least a couple of weeks to think over the details. Not here; not when he’s doing his own thing.

In another era, this was unthinkable. Deals could get interesting — even exciting at times. But it never enough to cause emotional upheaval.

Relan, on his own, is behaving more like a mid-sized businessman than a fat cat banker. Sure, he has a reputation, but that counts for nothing if he isn’t quick on his feet and doesn’t connect to the businessman on the other side of the table.

When you ask him how the fund is doing, he says, “We’ve done four deals. We could have done better.”

Nearly 1,400 kilometers away, on the outskirts of Mumbai, another private equity entrepreneur is in a celebratory mood.

“We’re bootstrapping,” says Renuka Ramnath, the Harvard-educated former ICICI Ventures veteran.

She celebrated July 14 as the founding day of Multiples, a $350-million private equity fund that she and her team have raised.

She celebrated July 14 as the founding day of Multiples, a $350-million private equity fund that she and her team have raised.

Her team has just returned from Lonavla, where she has a house. “We thought, ‘Why stay in a hotel?’ So most of us stayed in my house and a few stayed over at the housing society guest house. We got the work done and saved on costs,” she says.

The Entrepreneur Capitalist

Pause for a minute. Private equity players indulging in quick turnaround deals, cutting costs, slumming it out? Is nothing sacred anymore?

Exhale! The antiseptic cathedral of risk finance is slowly going the bazaar way. The suits called venture capitalists are turning into nimble “entrepreneur capitalists”.

Over the last two years, experienced private equity fund managers who’ve managed billions of dollars in institutional and large global funds have left to start their own shops.

Relan and Ramnath aside, consider this long list: Rajesh Khanna from Warburg Pincus, Subbu Subramaniam from Barings India, and P.R. Srinivasan, the man who succeeded Relan at CVCI, have all left. Khanna, Subramaniam and Srinivasan all want to raise a fund. Louis Miranda, the face of IDFC Private Equity, too is believed to be on his way out.

Then there is the interesting case of P.H. Rajakumar, who for over a decade was Mr. UTI Ventures; he now runs Ascent Capital, which was spun out of the original firm. By the time the next round of fund raising happens, Ascent will have no organisational relationship with UTI.

Now, stars in the private equity business have attempted to set up their own funds before. But each time the renegades struck out on their own, they failed and went back to work for someone else. To that extent, nothing’s new.

The reason we’re writing of the latest bunch of renegades is because we believe this time around, they’re here to stay.

Renuka Ramnath even offers a prediction. “Independent platforms will manage $10 billion-$15 billion by 2020.”

As more entrepreneur capitalists emerge, private equity will flow deeper into our industries.

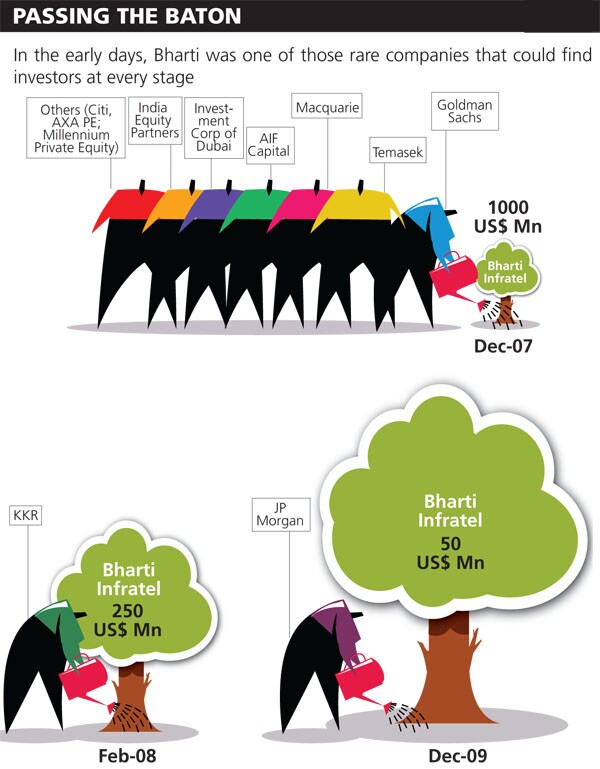

For instance, if Bharti was the darling of private equity investors in 2000, and a company that supplied Bharti with diesel power solutions, Acme Telepower, became the favourite in 2006, then expect the current lot to finance a company that may be the biggest supplier to Acme.

Rajesh Khanna, former head of Warburg Pincus in India, says, “Many entrepreneurs I funded when I was at Warburg said they had friends looking for private equity. But they were too small to attract large global funds. This was one of the factors that drove my decision to start out on my own.”

It’s different. No, really!

Of course, the current bunch of independent fund managers will have to defeat history. And they’ll be relieved some key variables are in their favour. The most crucial one is the change in the nature of the Indian economy.

Ashish Dhawan runs ChrysCapital Investment Advisors, the first independent fund to last 10 years in the country and deliver returns to its investors. he says, “Between 1993 and 2000, things were unclear. Take technology for instance. It wasn’t clear who would be bigger, HCL or Infosys. NIIT had a very high market capitalisation. Mastek had all the makings of being a big future company,”

Then there was the moment of madness in 1999 when funds set up shop to invest in Internet businesses and the Indo-US “corridor” play (holding company in the US; development centre in India).

Says Rahul Chandra, Director, Helion Advisors. “Many funds collapsed because of the dotcom bust. And the Indo-US corridor play had a limited upside because the India centre could at best save costs; it didn’t decide the fortunes of the US entity.”

Since predicting which company would top the sector charts was difficult, investing in unlisted and private companies was a mug’s game. Failure rates were high and eventually most investors played safe and deployed small amounts, almost insignificant parts of a company’s capital.

P.H. Raja Kumar, managing partner, Ascent Capital, says, “I was at Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) from 1993 to 2000. In those days, access to capital through venture capital wasn’t easy. Most funds that picked equity asked for debt-like guarantees. That is not true venture capital. All put together, a few hundred crores was all that was ever invested.”

Their financing did not influence the fate of the company. This has changed. Over the years, Indian entrepreneurs have gotten their act together. Bad loan levels — a proxy for company failure rate — have been consistently falling. Government policy is clear as well.

Arjun Handa, CEO, Claris Lifesciences, says, “Private equity investors are confident that if a company has reached around Rs. 700 crore to Rs. 1,000 crore, then in all probability it will double in size. They have a greater belief in the abilities of the entrepreneur as well as the appropriateness of regulation.”

Confident entrepreneurs understand this investor class better and are now more open to doing business with private equity funds. This wasn’t the case in 1993-1997.

Nitin Deshmukh, head, Kotak Private Equity is a veteran. “Few businessmen got rich on the back of an increase in market capitalisation,” he says. “For them, cash flow was more important. So they weren’t interested in accepting this ‘smart money’ to scale up and conquer the world.” He recalls how, in the early days, when he called a company to discuss business, he’d be directed to the accounts department!

Infographics: Sameer Pawar

It so happened then, that in many cases there was adverse selection. “Companies that were not the ideal PE investments were the ones that sought private equity,” says Dhawan. This, too, has changed. Many companies now realise they could use this capital to leapfrog competition. Take job site Naukri.com, for instance. It had competitors. But it could inch ahead because it attracted smart capital. G.M. Rao of GMR has often spoken about how IDFC — through equity as well as debt — helped it become one of the top infrastructure companies. Indraprastha Gas got investments from AIG Private Equity, which helped it hit the capital markets on time. WNS and Genpact became possible because some private equity investor was willing to take a punt on them.

Just the way companies are better run, even “independents” now have a better track record in investing. In the 1993-1997 phases, and even later in 2000, funds like eVentures, Connect Capital, Jumpstartup and Antfactory went down. Not for anything else, but because the people who ran these funds had a lot of learning to do as well. Today, each of these entrepreneurs has over 15 years of experience in using private equity. All of them can tell a good company from an average one. The larger pool of more experienced managers has also deepened the market.

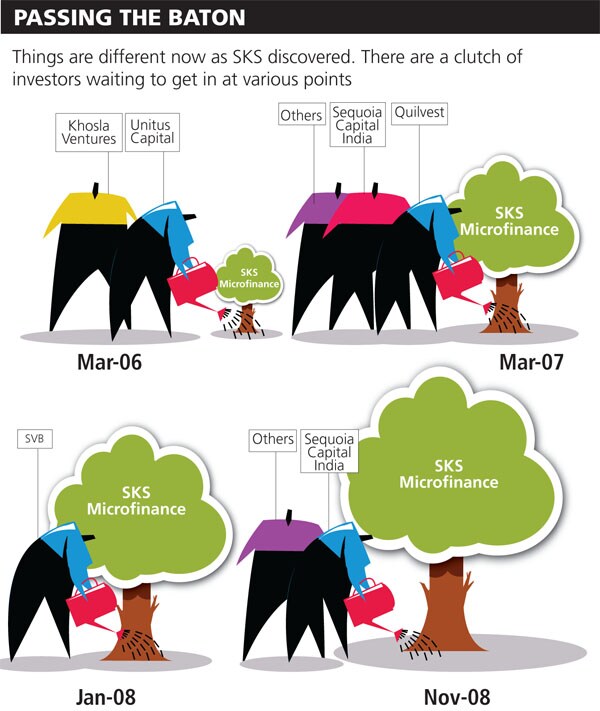

Earlier, when a private equity investor took a punt on a company, he had to stay with the company all the way until it went public. It was almost like running a marathon. If they sought a mid-way exit, there was little chance they’d find an interested buyer. “There was a fear that the guy selling out could be palming off a lemon!” says Relan. Now the depth of the market ensures that each investor runs part of a relay race that ends when the company goes public.

It was in 2002 that private equity really hit its stride.

That was when asset managers realised that there was something called business process outsourcing (BPO). And that this one was a business where there were no legacy leaders. Instead, they could fund and create them from scratch.

For Dhawan, this was a defining moment for the community. “The IT big boys were slow to spot this opportunity. Captives were looking for cost reductions. That gave the private equity guys a window. I think in 2005, of the top 20 BPO companies, almost 15 were backed by private equity players or venture capitalists,” he says. Good entrepreneurs made it easier for them to invest.

Law of small numbers

If India’s $1 trillion economy grows at 8.5 per cent over the next few years, it will produce $85 billion–$90 billion of additional goods and services every year. Multiply that by the incremental capital output ratio — the amount of capital needed annually to produce one unit of extra GDP — for India, which is 4, we get $340 billion–$350 billion of investment that will be needed to produce that extra $85 billion of GDP.