Havells India's Big Bite

Qimat Rai Gupta acquired a company much bigger than his and then fought hard to not lose everything he had built. His battle plan is now showing results

In his 73 years, Qimat Rai Gupta has survived many a crisis. But this was different. It was October 2008 and bankers in London were breathing down his neck. Barely a year ago the Havells India chairman had taken loans from them to acquire the European firm, Sylvania — a company one and a half times the size of his own company. Now Sylvania was making operational losses to the tune of 30 million euros annually and the worried lenders wanted their money back or wanted the takeover keys to Sylvania.

“Lenders were thinking of appointing a professional team to take over,” recalls Ameet Gupta, director, Havells.

Back in India, PE investors, bankers, well wishers, all had one advice — write off that investment and move on. Havells India had seen a meteoric rise, growing from Rs. 100 crore in 2000 to Rs. 1,600 crore in 2006, but they feared a sinking Sylvania would drag Havells down with it.

The mood at the company headquarters in Noida was sombre. Anil Gupta, the joint MD and son of Qimat Rai Gupta, was dispirited. Ameet, his cousin, was shaken. This was their first venture overseas and the decision seemed to be boomeranging. “We feared that we might lose the company,” Anil says.

But Gupta senior wasn’t ready to call it quits. At 73, he may be frail, but he decided to prepare Havells for a battle. Fixing Sylvania was their best bet, he reckoned, and the only opportunity to become an international player. For 15 consecutive days, he sat for five hours a day with his son and nephew and at times key executives, pushing them, motivating them. “This is a do or die situation. If you fail, the blot is on you. You will never be able to do any acquisition in your life or expand overseas. If you succeed, nothing will be difficult,” he told them.

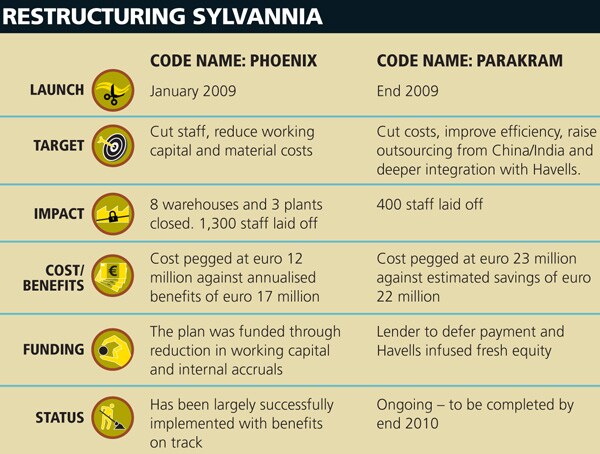

So, the Guptas put Sylvania through massive restructuring in January 2009. The CEO and some key executives were replaced. Anil and Ameet took charge. They laid off staff, shut plants and warehouses and restructured operations.

Today, Sylvania has stopped making operational losses, though sales are flat. By next year it expects to post profit. “We have been pleasantly surprised in the manner in which Havells has re-structured Sylvania. It is not easy to do it, more so in Europe. What has happened is impressive,” says Niten Malhan, MD, Warburg Pincus India Pvt Ltd.

Why the Crisis?

Beyond the economic crisis, there are good reasons why Sylvania went on the bleeding path. Havells had acquired an MNC bigger than itself, but “did not have the management bandwidth to manage such a big company”, says Ameet.

Havells is a first-generation company that Qimat Rai Gupta founded in the 1970s. He started out as an electrical goods trader in Delhi’s Bhagirath Place (a wholesale market for electrical goods). In 2005, with around Rs. 1,000-crore revenues, Havells India was itching for more. It bid for UK-based Electrium but lost it to Siemens. In 2006, when N. M. Rothschild, an investment banking organisation, called to ask if they would be interested in Sylvania, it took the board just about an hour to give its nod.

The challenge was that Havells was looking for a $60-70 million target, but at a $300-million bid price, the Sylvania deal was far bigger. It was almost 1.5 times that of Havells in size. The Guptas stretched themselves, aided by a debt-free balance sheet and good track record, to debt finance the acquisition.

Through the fast-paced bidding process, they had little time to think ahead. It was on January 31, 2007, when they finally got the exclusive bid rights that it began to sink in. “I couldn’t sleep the whole night,” recalls Ameet. Their was Havells’ first overseas acquisition. The Guptas thought keeping the old Sylvania management onboard was their safest bet. The bankers and investors preferred this stability.

But Sylvania wasn’t a normal company. Over the last 15 years, it was managed and controlled largely by the PEs, not strategic investors. From the leaders at the top to the way business was managed, “everything was geared to window dress the company,” says Anil. Between 2007 and end 2008, Havells managed Sylvania like a financial investor, motivating and inspiring the team from a distance. Once in a few weeks the Guptas would travel to hold meetings and get updates. “Sylvania was a large organisation. You get overwhelmed. So you won’t change the sail but make small changes,” says Rajiv Goel, senior VP, Sylvania secretariat.

Sylvania’s leadership didn’t make it any easy. “Their approach was, these guys from India don’t understand Europe,” says Anil. They would all sit down to thrash out strategies to fix things. But once they returned to India they would realise that nothing moved. By October 2008, Sylvania was bleeding and jittery lenders were threatening to take over the company.

“We told them that Havells is your best bet. Give us time,” says Anil. The Guptas acted swiftly, putting Sylvania through a massive restructuring exercise with edgy bankers monitoring them.

Cleaning Up the Mess

The CEO and three other key executives were removed even as Anil took charge of Europe and Ameet of Asia and the Americas. They shifted five senior executives from India for three-four months, and appointed their own CFO. “Once we took charge we realised that there is enough flab to bring down the cost structures,” says Anil.

Sylvannia’s problem was that sales had shrunk and plants operated at half the capacity even as costs remained high. Layoffs in Europe and the Americas were central to restructuring plans.

Now it’s not easy to layoff people in Europe. Two things helped. One, Sylvania execs were expecting it since 2007. And two, the economic recession was claiming victims everywhere. When Havells started the process by end 2008, there wasn’t much protest. “All they were worried about was the settlement, not the job,” says Rajesh Bhatia, vice president, (IT & HR), Havells Sylvania.

Since the retrenchment was spread over eight-ten countries with different rules and regulation, Havells engaged a European law firm to help navigate in each country. The strategy was to convince the local management of the need to restructure and then let them take charge. “The nitty-gritty of restructuring was left to the local GM. We knew that if you put an Indian face you would be clobbered,” says Bhatia who led the layoffs. John Smith, the current executive VP (operations) Sylvania Havells, who has had rich international experience and has seen many a restructuring during his 25 years at P&G was a good sounding board.

The operations heads were largely left untouched. In technical areas like supply chain etc., Havells executives travelled for brief periods. “We were cautious in sending people from HQ. The approach was never to go and boss over them but find answers to bring down the cost,” says Anil. That worked as the Sylvania executives did not feel threatened.

Of course, not everything went according to the script. In Italy and Spain, services to customers got affected and targeted savings could not be achieved. But overall, the results have been good. “We have cut euro 35 million in our costs in 18 months,” says Smith. Today, while sales have remained flat, the euro 30 million operational loss posted in 2009 has been stemmed. By 2011, they expect it to make profit of around euro 30-35 million.

Gains show beyond the financials too. “We have created a level of innovation that we haven’t seen in our lifetime. Today 40 percent of our inventory is of new products,” says Smith.

Looking Ahead

Even as they restructure, the Guptas are preparing for the future. “We are laying the foundation for our next growth phase,” says Gupta senior. High on priority is a smooth integration of Havells India and Sylvania to tap into each others’ strengths and enable expansion into new products and new geographies.

Havells will leverage Sylvania’s global branding power. It will bring the Sylvania range of lighting to India this year to compete better with MNCs like Philips. It will also launch into new markets (like China) or introduce new products in existing markets like Latin America and Asia under the Sylvania brand. The plan is to nudge Sylvania towards faster growing markets in Asia, shifting away from slow-growing Europe. The Guptas hope that revenue contribution would shift from Europe (65 percent), Americas (approx 30 percent) and Asia (approx 5 percent) to Europe (50 percent), Americas (30 percent) and Asia (20 percent).

The manufacturing strategy too will change in tandem. Outsourcing from low-cost centres like India will increase as “production cost is 25-40 percent lower”. Between 2007 and now, outsourcing for Sylvania has already gone up from 35 percent to 50 percent with special thrust on India. Backend functions like IT network management, finance etc., are now being done out of India. Competing with MNCs and R&D will remain a priority. Havells India has a 200-member team while Sylvania has 100 people in lighting — 40 in Europe and 60 in India. The India staff will double in the next two years.

Havells India is also adding new revenue sources with products like geysers, rice cookers, and mixers. It launched fans in 2003 in the premium Rs. 1,000 plus category with energy efficiency as their USP. They claim they have already become the No. 3 in value terms, ahead of Bajaj. The new products don’t require significant investments and Havells is looking to ride on its strong branding to lure customers. The Challenges

Will the Guptas be able to pull this off?

“The Havells Sylvania merger is complex. It involves too many transitions at the same time,” says Smith. A first-generation 73-year-old entrepreneur passing on the baton to his son; a company gobbling another that is far bigger than itself; and all this even as it tries to globalise. “Typically a company does one-two of those things at a time. So many things at the same time — at least I haven’t seen it,” he says.

Besides, Sylvania and Havells are like chalk and cheese. The former is steeped in a slow, stable, structured world of processes and hierarchies. The latter is an entrepreneurial powerhouse that is flexible, ambitious and aggressive, leaning heavily on gut feel. But Havells lacks the managerial bandwidth to handle Sylvania.

Yet, early signs are encouraging. On a recent Tuesday, a business unit wanted to make a euro 75,000 marketing investment. Three years ago it would have taken Sylvania a month to approve that. “We made the decision in 10 minutes. They talked to me. I set up a call with the COO and all the country managers and the decision was taken. That’s Havells’ culture. Leaders are highly interactive. There is always a sense of urgency hard to miss,” says Smith.

Things are changing but it will not be easy. “There is tremendous discomfort [about the new way of working]. But there is a critical mass that has become comfortable,” he adds. But there is no denying that this transition will take several years.

Havells has become an MNC overnight with a presence in 50 plus countries. While absence of structures and processes bring agility, it will also bring chaos as the company scales up.

Havells is aware of that. The CFO, Rajesh Gupta, says they initiated a programme on risk management where every Havells employee was asked to list the risk they see the organisation faces. They compiled 600 such risks, which vary from operational procurement issues, HR and accounts. The list is being tackled and is now down to 13. Procurement policies have been overhauled, inspired by Sylvannia systems. Checklists have been prepared for every step in the procurement process. If there is a slip up at any point the system throws it up automatically.

Kuldeep Kumar Aggarwal, a Havells dealer, who does Rs. 60 crore worth of business annually with Havells, says earlier he had to book orders manually. Now everything is automated. Inventory can be checked, orders placed and tracked in real time on the Havells portal. Inspired by Sylvania, they have created a central warehouse in Sahibabad in Ghazaiabad district, UP, to facilitate this.

Nowhere is the challenge more acute then building a leadership pipeline. “If we have to buy Sylvania again we must have enough management bandwidth to manage it,” says Anil. From succession planning to grooming talent by exposing them to difficult assignments — Havells is tapping into both India and Sylvania staff for this. “The good thing is they listen. And once they realise it [the problems] they move very quickly,” says Smith. Will they be able to “maintain the magic” as they scale up and put in place structures and processes?

The answer will hold the key to Havells’ future.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)