Greed is Back on Wall Street

Gordon Gekko, the icon of greed, returns to screens after 23 years. Perfect timing, as Wall Street shrugs off lessons from the crisis and goes back to its old ways

It all starts with plunging necklines and super miniskirts. The evening begins promisingly for the clutch of young and old men at the Turtle Bay tavern on 2nd Avenue in New York’s Midtown East. Steaming hot girls linger coquettishly around them, serving shots of alcohol and naughty banter. Each man repeats his order just to keep the girls around him.

The girls know what they’re doing. It isn’t the cheap liquor that is selling. It is their flirtation. If all goes well, when the bar closes, each girl would go home richer by $300 or even $600. Where on earth can a 20-year-old make that kind of money for a few hours of fun? It is almost the kind of returns that Wall Streeters make.

Wait. Did the girls tell you they are, in fact, employed by two ex-Wall Street Bankers who quit their careers after the 2008 financial crisis and founded a shot-girl outsourcing business operating pretty much on similar principles?

The Wall Street Journal reports that JP Morgan analyst Bryan Auld and his buddy from Bear Stearns, Dominic D’Aleo, have built a profitable business renting out shot girls to NY bars that sell for $3 or $4 drinks that cost 25 cents to make. It is not just the mark-up that is so typical of investment banking; the ‘Shot-Girl Bible’ they have written detailing the best practices their employees must follow reads pretty much like a dealmaker’s canon. Take rule #7: Each interaction with a potential customer is an investment, and even an unpromising start usually yields dividends by night’s end. The next rule is more direct. #8: Dress sexy.

But unlike the mirth of some drunkards that ends in an evening, Wall Street is an eternal cycle of boom and bust, where greed and panic rule alternately.

And here is fresh news on this somewhat old subject. The worst financial crisis in eight decades has utterly failed to change this routine. Surely, the US government is determined to change forever the way Wall Street functions through a restriction on proprietary trading by banks, curbs on executive compensation, bringing over-the-counters derivatives onto exchanges and a strong attack on the “Too Big to Fail” mindset.

But all that has not stopped Wall Street from going back to the party. Despite the US economy being in a shambles, the great moneymaking machine on the Street has cranked up to life and is well on the way to creating the next bubble. Ironically, the same banks that were saved with taxpayer money just 18 months ago are now getting virtually free government money to play out their wagers.

In other words, the culture of greed has returned to Wall Street.

Street Never Sleeps

Not that greed ever went away, or so believes filmmaker Oliver Stone, the man who created Wall Street amid a massive insider trading scandal that led to the 1987 ‘Black Monday’ stock market crash. It was 23 years ago that Gordon Gekko, the scheming villain in that movie, patiently explained: “Greed, for want of a better word, is good.” He must have touched a raw nerve somewhere, for the phrase remains the most defining statement about Wall Street till today.

“When we made Wall Street in 1987... We didn’t expect the world to embrace Gekko,” Stone tells Forbes India in an interview. “He was a bad guy and people should have learnt what not to do and moved on. But Gekko stayed in the mindset of the Wall Street aspirants.”

Naturally, Stone had to revive Gekko to feed the appetite of a new generation. He does that in his just-released movie Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps.

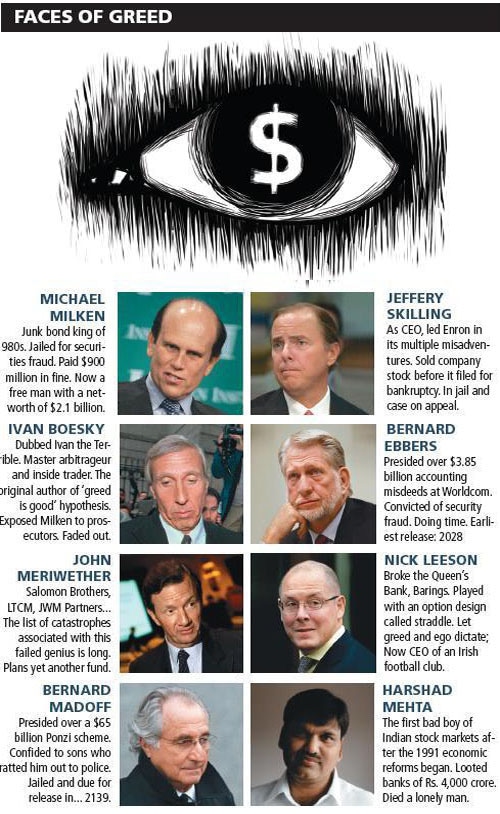

The 1987 crash was the biggest calamity the world had seen before the 2008 crisis. Just like now, many expected the mandarins of the markets to learn their lessons. But as things turned out, the markets only spawned some of history’s most notorious punters in the following years. With every scam, the size of the hit multiplied. The short history of greed on Wall street in these years reads like a relay race that climaxed with a mega $65-billion Ponzi scheme by the now discredited Bernard L. Madoff.

By the time Wall Street released, junk bond king Michael Milken and arbitrageur Ivan Boesky had already come under investigation on charges of stock manipulation, insider trading, stock parking and countless ways of earning illicit profits. The character of Gordon Gekko derived a lot from these two extraordinary gentlemen; In fact, Gekko’s pontification on greed was based on an extempore remark by Boesky in a speech to students of UC Berkeley in 1986.

But as soon as Milken and Boesky had been jailed, new scandals erupted. Salomon Brothers was caught rigging the US Treasury bond auction. Its vice chairman John Meriwether left to launch Long Term Capital Management and presided over the hedge fund’s spectacular failure (total loss $4.6 billion) in 1998. In time, he developed into some sort of a serial hedge fund adventurer. He started JWM Partners within a year only to fail investors again. JWM closed down in 2009. (By the way, Meriwether is now ready with his third hedge fund. This guy has got guts).

Early 1990s were also the time the equity cult spread in Asia. The Wall Street inspiration echoed in India where whiz kid Harshad Mehta swindled as much as Rs. 4,000 crore from the banking system to rig the stock market. In 1995 in Singapore, British derivatives broker Nick Leeson broke Her Majesty’s Bank, Barings, by shorting option combinations called straddles and losing the bank 827 million pounds, or twice its capital.

By the turn of the millennium, the era of accounting frauds combined with insider trading was truly ushered in by Enron and shaped to finer details by Worldcom and Tyco.

Crisis, What Crisis?

Remember Dick Fuld? Called ‘gorilla’ by fellow Wall Streeters for his competitiveness, Fuld plunged Lehman Brothers in the subprime bubble and left it with liabilities of about $630 billion. With Lehman filing for bankruptcy, everyone thought Fuld’s career was over.

In May 2010, Fuld made a quiet comeback to Wall Street. He has become the CEO of a penny-stock firm called Legend Securities (address: 45, Wall Street).

Illustration: Sameer Pawar. Photographs: Michael Milken: Fred Prouser / Reuters; Ivan Boesky: Bettmann / Corbis; John Meriwether: James Leynse / Corbis; Bernard Madoff: Brendan McDermid / Reuters; Jeffrey Skilling: Mike Theiler / Reuters; Bernard Hebbers: Martin H. Simon / Corbis; Nick Leeson: Kieran Doherty / Reuters; Harshad Mehta: Baldev Kapoor / Corbis.

Perhaps his comeback signifies the return of the gung ho era that existed in the pre-crisis days. A full-fledged spiral of liquidity, leverage and excessive risk-taking has taken hold on the Street. Veteran insiders say at least one bubble — and possibly two or three — are building up. “And the irony is that it is all completely encouraged by the US government,” says a veteran insider who works at the NY office of a large European bank.

The new excess is taking place in the government bonds market. Even as Americans are facing a squeeze in credit, the banks that put them there are getting virtually free money. The Federal Reserve has kept interest rates in the range of 0-0.25 percent with the hope that it would encourage banks to lend to people and businesses. That has not happened because the economy and the job market are in the dumps. However, investment banks have readily queued up to borrow from the Fed. They put this money in government bonds which currently give a yield of about 2.6 percent. “They are borrowing from the government and lending it back to the government by buying bonds. The taxpayer, who is suffering from a lack of credit, effectively pays 2.6 percent to the rich banks,” says the banker. The only consolation here is that the levels of leverage are lower than what they used to be before the crisis.

In the US, pension funds have a compulsion to earn a minimum rate of return (in ‘teens’ as they put it) because they have promised to pay a certain level of pension to the elderly. With interest rates low and the stock market in the garbage van, they aren’t able to sustain the returns. They are going to ‘alternatives’ like hedge funds. Forced to seek superior returns by such investors, the funds too, have jumped into the free money bandwagon. A lot of US money is being sent abroad for carry trades, buying of bonds and currency in higher yielding economies.

“The low interest rates are acting as a catalyst of a new bubble,” says Viru Raparthi, a former investment banker who has co-founded MARV, a toxic asset cleanup consultancy. “Banks have to grow and show profits. They are trying to find new ways of getting returns in the teens. The whole cycle has started all over again.”

Why should easy arbitrage be considered a bubble? For one, it is highly leveraged. Since government bonds qualify for the repo facility, banks that buy $100 worth of bonds with borrowed Fed money, can go back to the Fed and borrow $97 against those securities. This money is then used to buy more bonds which, in turn, are leveraged too.

The arbitrage works only as long as inflation remains extremely low. If inflation were to rise, the gap will quickly close and the entire brotherhood of the financial world will come to the market at once to sell. That will crash the bond market.

American corporates have a different dilemma. Consumer demand hasn’t risen and investment opportunities have virtually dried up. But, according to Moody’s Investor Services, US non-financial companies are sitting on a cash reserve of nearly $3 trillion, the highest in the last 50 years. Where will they put this money?

The answer came in August, usually considered a slow month for M&As. In the first three weeks alone, US companies announced M&As worth more than $175 billion, a sharp rise from $13 billion in the same month of 2009. Hostile bids and leveraged buyouts are all the rage again. Hedge funds, with half a trillion in cash, are ready to add their muscle to this game.

There are other companies rushing to raise money through initial public offerings. So far in 2010, as many as 87 companies have issued stock raising $12-13 billion, or more than four times the money raised in the same period last year. Another 170 companies have lined up IPOs to raise $60 billion. Neither the companies nor the investors are bothered that cash already in the system is lying uninvested.

Wall Street insiders openly say many of these bets could fail but nobody wants to stop the action for now. The clue to understanding this apparent dichotomy lies in the way the Street measures performance and rewards people.

Pay Day

On January 21, Goldman Sachs Chairman and CEO Lloyd Blankfein left a voice mail for his employees. It was bonus time and Blankfein’s message was simple: “In a year that proved to have no shortage of story lines, I believe very strongly that performance is the ultimate narrative.” In effect, he was saying the outside world should not interfere with his right to retain talent. The bank earmarked more than $16.2 billion for its employees, lower than $20 billion it was expected to. Despite the moderation, America saw an average bonus of half a million dollars per employee as a continuing sign of excess.

The whole of Wall Street revolves around the concept of base pay and bonus. It is an employee’s business, not the shareholders. (The last time a strong shareholder dictated terms on Wall Street was in 1992 when Warren Buffett fired Salomon Brothers CEO John Gutfreund after the Treasury scandal.)

“With its big money, Wall Street attracts extremely bright, hardworking and borderline ethical people,” says the European bank insider. There is only one yardstick for performance. Revenue. Pay and bonus are a direct result of how much revenue one brings in. So each employee clamours to show how he structured a certain product or got a company to do a merger. Arguments break out over competing claims. “Most guys who work in finance sector have no interest in making anything real,” says Satyajit Das, derivatives expert and author of Traders, Guns and Money. “So they like finance which operates at a meta-layer. It is capitalism distilled to its essence.”

The average span of a Wall Street career is 15 years. By the time someone rises near the top, he gets just one chance to make his millions. “Life in finance in that sense has a brutality that is quite its own,” says Das. “It is like the Serengeti and you have to be the lion not the gazelle. Then you have to compete with other lions!”

Sure enough, many in the real estate and commodity desks of Street firms who drove up the markets during 2005-2007 are no longer there. It is the turn of bond desk guys and forex fellows. When the next tide washes away, they’ll be gone and a new set of money hounds would have taken over.

Already, life has become more difficult for the average Wall Streeter. He can no longer lead a lavish life, launching bidding wars on Manhattan apartments, driving flashy cars and running up five-figure restaurant checks. With the economy down in the dumps, he has to keep the enjoyment muted.

That’s why Wall Streeters are extremely annoyed when the public and government impose limits on compensation; or when new rules curb their creativity in structuring products. The Street’s attitude problem has returned, says Yves Smith, author of ECONned and a former staff of Goldman Sachs, Sumitomo and McKinsey.

“The narcissism of the industry is appalling,” he says. “It is like that of a teenager, who after he wrecks his father’s car, is upset because he isn’t getting a new car.”

(Additional reporting by Shishir Prasad)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)