Fortis Has a Renewed Focus on India

By selling global assets, Fortis is cutting losses but does that justify the method in its acquisition madness?

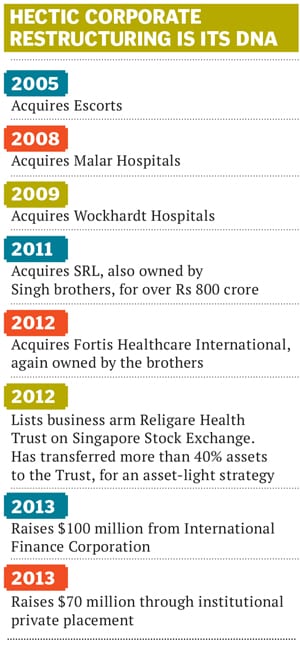

It was fast and furious. Fortis was on steroids; it made eight acquisitions in six countries in 15 months. The Singh brothers, Malvinder and Shivinder, promoters of Fortis Healthcare, were epitomising what some management mavens would call a shoot-first-and-then-ask-questions strategy. But in less than 24 months, it’s all unwinding: Two of the three biggest global assets are sold and the third, Quality Healthcare in Hong Kong, which was the first international buy for Fortis International when it was floated in October 2010, is up for sale too. When that happens in the near future, Fortis, for all practical purposes, will be back to being an Indian company.

“At every transformational step we have taken, we have been asked why,” said Malvinder Singh in a Forbes India interview in March 2012 . “When we exited Ranbaxy [sold to Japan’s Daiichi Sankyo for $2 billion], bought and sold our stakes in Parkway Holdings [Singapore arm of Parkway Pantai] and now, when we have taken Fortis global; each time we have been asked ‘why’… I don’t blame the analysts for asking questions, but we are doing what is best for the company, which is to become a leading, international integrated health care player.”

When the company announced the sale of its Vietnam unit in June 2013, analysts didn’t ask many questions. The highly leveraged balance sheet provided the answers. Nonetheless, these decisions mark a considerable U-turn in Fortis’s strategy. The 50:50 split between international business and Indian business in 2012 is now changed to 30:70. When Quality Healthcare goes, the ratio will change further. Fortis wants to focus on India, says the management now. What then becomes of the global ambitions? Did those roughly right decisions come at a huge price?

No gain, much loss?

“There’s no benefit at all,” says a health care analyst with an investment bank in Mumbai. “They can make some money when they sell Quality Healthcare, but in reality it’s time lost. They’ve lost focus… if they were not so cash-strapped they could have done more in the Indian business.”

Group Chief Executive Vishal Bali doesn’t agree. Even while this massive corporate restructuring (see graphics) was happening in 2010-12, he argues, the India business grew its revenue by 20 percent and the margins remained solid. “That’s no mean feat…We’ve added two new hospitals in Gurgaon and Kangra,” he says. To be fair, Fortis’s flagship hospital in Gurgaon is considered by many, including their medical technology suppliers, to be one of the top 10 hospitals globally as far as the infrastructure goes. It’s even going to have a movie theatre!

In this complex financial ‘jugglery’—a part of the Rs 6,500 crore debt that the company now has was taken to finance global asset acquisitions and now those very assets are being shed to deleverage the balance sheet—the markets and investors are looking at the frenetic buying and selling as merely investment and divestment. (All the acquisitions and subsequent investment by the promoters in those assets—$583 million plus $80 million and sold to the India business as one entity for $663 million—are seen by many investors as overpayment. The management, however, says it was sold on a no-profit-no-loss basis.)

Bali wants to hold his ground. The group has had major learnings that will benefit the India business, he avers. Fortis has demonstrated its ability to do post-merger integration not only in India but at the international level, which is a big strength. “One may want to do it again in a couple of years’ time,” he says, not ruling out another global foray by the Singh brothers.

But the key learning for which Bali, as the top executive responsible for international business, would like to take credit is the fact that Fortis grew the businesses in other markets even though they were in different verticals and formats. “If any of these businesses had de-grown under us, then one could say we have failed,” he argues.

When Fortis exited Dental Corp in Australia, it had grown from 130 practices to 190. But did Fortis make money on its sale? Not quite; it was sold almost at par. Bali says that’s because the Australian consumer-spending environment, six months prior to the sale, was at an all-time low and dental being an all-cash business, it hurt the valuation.

In Vietnam, the business grew by 18 to 20 percent and the margins swelled to 35 percent, numbers that the company had never seen in its lifetime. In Hong Kong, Quality Healthcare had traditionally grown at 3 to 4 percent but under Fortis it grew 8 to 10 percent, and margins were up from single digits to high double digits. Even in Singapore, which is a mature health care market and businesses hardly see spectacular growth, Bali claims that at Radlink, a radiology asset in its portfolio, the margins have grown 20 percent.

These gains may be consolation, but there’s no denying the reversal. From the original idea of creating an international Fortis brand, listing it in Singapore and creating India’s first integrated, multi-vertical health care organisation, to being forced to sell the global entities and face a long, agonising phase of stocks de-rating, Fortis clearly hasn’t had much luck. Rubbing salt in the wound is the fact that the divestments are happening when the stock is trading at merely Rs 80 to Rs 90, as against the earlier price band of Rs 150 to Rs 160, says an analyst with a brokerage firm in Mumbai. The debt-equity ratio is certainly down from 1.6 in March 2012 to 0.55 at present, but people remain cautious in their comments.

From a financial perspective, the knotty corporate restructuring isn’t conducive to the India business. They are giving away more than they can make. For instance, the rental Fortis is paying to Religare Health Trust is more than the earnings before interest, depreciation, tax and amortisation (Ebidta, nearly Rs 400 crore in 2012) of its hospitals. “Minority shareholders are still unhappy, believing that they have had to pay for the promoters’ business instead of common sense,” says an analyst, explaining why the stocks are still depressed.

Bali believes once the company shows three to four steady quarters, stocks will bounce back. But stock market veterans have a different view. Markets have changed their valuation parameters in the last four to five years, says market expert SP Tulsian in Mumbai. “They don’t look at the capital assets of the company, they trade on the profitability,” he says. He believes many Indian conventional businesses have bet on brick-and-mortar assets thinking even if they faltered on financial performance, the high domestic inflation rate of 10 percent would ensure they made money in four to five years on their resale values. He says most promoters went wrong, including the Singh brothers. Incidentally, the two brothers were earlier this year embroiled in a controversy regarding their erstwhile company, Ranbaxy Laboratories, over regulations.

From Asian sprawl to Indian calibration

One of the logical outcomes of the so-called global integrated model for the company would have been cross-leveraging talent and processes from different units. A global supply chain would also have enabled centralised procurement, lower costs and higher margins. Now the supply chain isn’t global any more, but the company says it has still managed to get the best out of it. Its global head of supply chain, an ex-Philips executive, has now relocated to Delhi. The integration of the supply chain has reduced the cost by 6.5 percent in just one year, says Bali. Working with Infosys BPO, Fortis has already integrated the services backend.

From the medical side, clinical groups from Singapore, especially in colorectal cancer, are collaborating with the Indian teams. The head of nursing in Singapore will help the India business to set up its nursing protocols. “So, on the operations front, one can already see influencers of the global expansion,” says Bali.

Fair enough. But now that the focus is on India, apart from growing regional hospitals like Manipal and Narayana Health, it’s the dozens of small-format, specialty care chains that will chip away at the hospital business, and profitability in particular. In 2012-13 alone, at least 10 such chains received venture funding. Fortis, which has grown by aggressive acquisitions, prides itself on it, saying, “We’ve done in 10 years what Apollo did in 25 years.” But it now has to look beyond its traditional emphasis on scale, which, in a sense, has also defined the Indian health care business model.

“India is defined by [number of] beds, rather than competencies,” says Suresh Soni, founder and chief executive of Nova Medical Centres, which has attracted medical talent from Fortis. That’s a wrong model, he believes, where there’s a race to fill hospital beds, many times unnecessarily. On the contrary, health care providers should be in the operating room business. This has been standard practice around the world for the last 30 years, he says.

Nova has begun a new format in India called ‘short stay surgical care’ that is spread across many specialties. In three years it has built 12 operations facilities across seven cities, is clocking Rs 300 crore in revenue and claims 20 to 25 percent lower pricing than tertiary care hospitals for surgeries. Scale, for Soni, is a “phallic symbol”. It’s like assessing a pharma company by the size of its factory rather than the strength of its scientific talent in formulations, he argues.

Nova is not the only one. From nephrology to general physician practice to eyecare, small format health care providers, pumped with private equity investment, are springing up all over. Bali is conscious of the competition, even though the emerging rivals are small right now. He believes it’s where the company’s global experience, even though shortlived, would come in use. All the Asian buys were in formats and specialities that were never part of the Fortis portfolio—primary care (Hong Kong), dental care (Australia), radiology (Singapore), general practice (Vietnam). The experience of managing and growing that may help in India as they look to grow.

Predictably enough, Fortis will add more beds: 1,000 in the current year and 500 in each of the subsequent two to three years. It intends to optimise the existing assets. Of the inherent capacity of 10,000 beds, 5,000 beds will be operational by the year-end; the rest of the capacity will be expanded over time. “We’ve also come to understand now what is a good optimal bed size; 200 to 250 beds make a profitable proposition,” says Bali.

Still, these new formats are now seen by Fortis in a new light—of scalability. Two of these that have existed in the group, C-DOC in endocrinology and Renkare in nephrology, have remained National Capital Region experiments. In time Fortis may want to grow them. A senior executive at one of its rivals says Fortis is even planning to pare down its “stake in the pharmacy business” where it owns more than 100 stores. If that is correct, it’s easy to rule out another aggressive acquisition that Fortis could have made—of MedPlus, one of the largest pharmacy chains in the country after Apollo’s pharmacy business. People cite the new drug price and control order, which caps the prices of over 300 essential drugs in the country and squeezes the margins of pharmacies, as the reason for the rethink.

In an interview to a business daily in 2011, Shivinder, the younger of the Singh brothers, had said: “Talking about benchmark, we don’t really compete with the Indian players. We want to be globally respected. We have done a lot of investments and spent a lot of time to create a standardised, replicable model.”

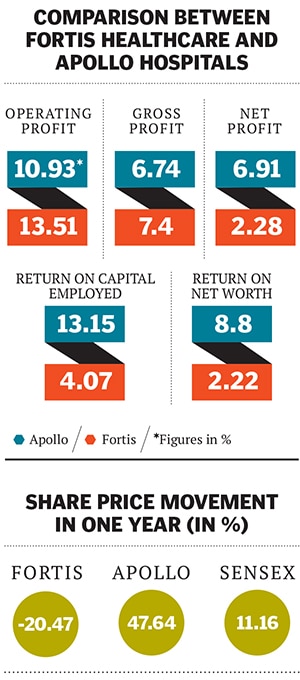

Maybe it’s time to create a few more models to match Apollo’s performance on the stock market (see graphic). “As a group they have aggression, but unless they cut their losses and make their business manageable, there’s no point in making claims that they are number one in Asia. Everything boils down to cash profit,” says Tulsian.

The Singh brothers came relatively late to the health care business, but they moved fast. It was clear that they wanted to show that wars are won in the beginning, not the end, as movies often portray. With miscalculations on their global expansion, they may have been forced to look at the domestic market more closely but, as one analyst says, “With them you can never say what they’ll do next.”

(With additional reporting by Nilofer D’Souza)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)