Fat Fingers,Traders and Algorithms

India's stock markets are at the beginning of a major change. And for once, it is the machine before the man that counts

When I woke up on the morning of May 7 and tuned into CNBC-TV18 as I always do first thing, managing editor Udayan Mukherjee was describing what had happened on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) while I was sleeping. Around 2:42 p.m. (New York Time, May 6), the Dow Jones — easily the world’s most watched stock market index — had gone into a free fall. In just about five minutes, it plunged 573 points. And then 10 minutes later, by 3:07 p.m., it had rocketed back 543 points. Traders on Wall Street and market regulators in the US had gone into a funk.

Michael Peltz of the Institutional Investor wrote in an investigation in the magazine: “Shares of Procter & Gamble, the ultimate defensive blue-chip stock, dropped more than one third in a matter of minutes before recovering almost as quickly, all for no apparent reason. A few other large US companies, including consulting firm Accenture, saw their stocks trade as low as a penny a share, only to close not far from where they had begun the day (nearly $42 a share in the case of Accenture) — again, on no news.

“By the time the dust settled, a whopping 19.3 billion shares had changed hands, more than twice the average daily US equity market volume this year and the second-biggest trading day ever.” The aptly named ‘flash crash’ temporarily wiped out more than a half trillion dollars in equity value, shaking what little faith nervous investors had in US markets.

When the stock markets opened in Mumbai, no tremors were felt. Because by then, it was “evident” this was a fluke — one of those events triggered by a few “rogue traders” and “algorithms gone wild”. Not surprisingly, the story ran its course in the media and fell off most people’s radars in India. Except a tiny minority, including me, who believe that what happened in the US was a precursor to how dramatically stock trading will change in India as well.

Then of course there is the little fact that this event lies at the intersection of two interests that have occupied me for as long as I can remember. First, I’m a sucker for what you’d call ‘quant investing’ — the application of mathematical techniques to financial investments. Second, I’m a sci-fi buff — and May 6 sounded like the kind of thing that could only happen in a Neal Stephenson book.

Anyway, to get back to what happened on the day, let’s first get a bit of background right. Until the late Nineties stock trading was a straightforward affair. Buyers and sellers gathered on market floors, haggled a while until they arrived at what both believed was a fair price, shook hands, and completed the deal. Then the US regulators opened their stock markets to electronic trading — which meant anybody with access to a computer could connect to the exchange and execute an order.

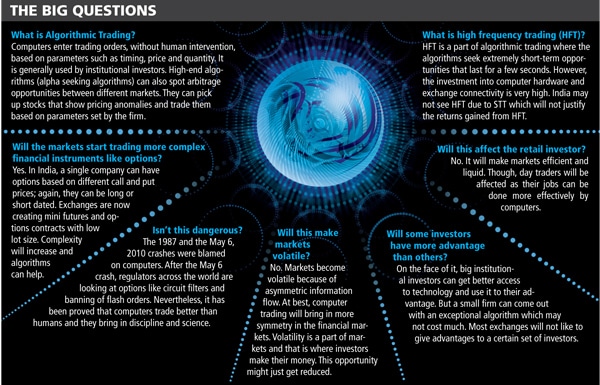

Electronic trading in turn created new market places. Not just that, computing power in the hands of ordinary people started to multiply exponentially. Soon stock traders figured if they brought mathematicians into the business, they could work together on building powerful algorithms that computers would run to scan markets for opportunities, spot trends before anybody else could and change orders and strategies in milliseconds. Now called High Frequency Traders (HFT), they use brute computing power to move faster than any human trader can, execute an order, book profits and get out before anybody even figures what really happened.

Infographics: Vidyanand Kamat

These capabilities have often alarmed Luddites enough to argue computers will eventually take over stock markets and trigger events beyond human control — like on May 6 when a few hundred algorithms went berserk and brought the financial system to its knees. I must confess I don’t particularly care much for the Luddite stance. Sure, till date, nobody knows what really happened. What everybody has are theories, and the theory I think the most plausible is the “electronic fat finger” — essentially, a bug in the system that fired the wrong order. Bugs, however, can be fixed.

In the larger scheme of things as I see it, HFTs add liquidity, speed up execution and narrow spreads, all of which eventually contributes to a far more efficient market place. Be that as it may, since then I’ve spent time talking to various people trying to understand what is happening closer home. Short answer, a lot! And I’m going to spend some time talking of these changes and how it will eventually change the face of our stock markets.

The way things are, only 8 percent of all trades on Indian markets are associated with algorithms. In more developed markets though, this number is as high as 80 percent. On the face of it, that doesn’t sound an impressive enough number to merit attention. Which is why, when I heard Dr. Giles Nelson was in India to meet stock brokers and exchanges, I was intrigued.

Nelson works for Progress Software, an American company that built Apama, an algorithmic trading tool and a large player in the complex event processing space. Nelson told me he’s here because he can’t afford not to be here. Three years on the outside and he reckons at least 30-40 percent of all trades on the Indian markets will be powered by algorithms.

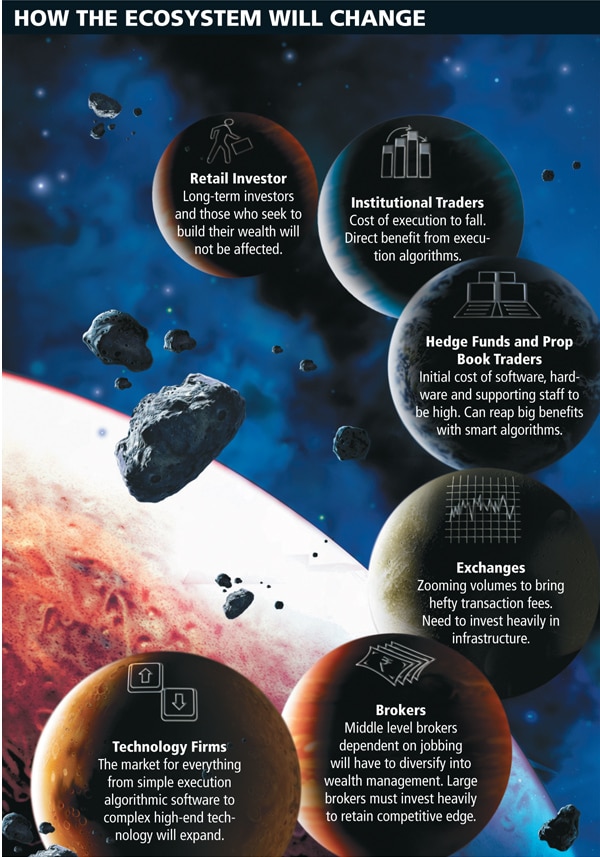

If that indeed happens, all short-term opportunities in the financial markets will go to institutional investors that have access to these tools, practically pushing day traders out of the system. To figure out if there is indeed any evidence of this happening, I walked into the offices of Magnum Equity Broking in central Mumbai.

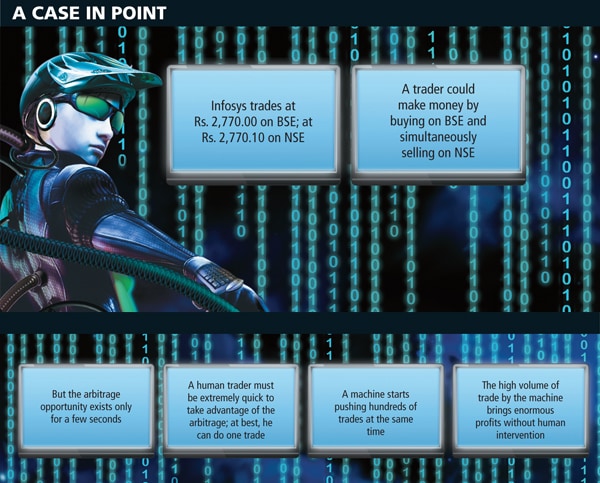

Once upon a time, it was a common sight to see trainee jobbers here practice how to execute trades on high-speed computers. Once a jobber was proficient enough to place one trade every three seconds, he was moved into real time trading. What they looked for was arbitrage opportunities. When markets are inefficient, profits here can be high. Three years ago, the difference between the cash and futures prices on the Nifty was as high as 7 to 8 percent. So, if a stock was priced at Rs. 100 in the cash market and Rs. 108 in the futures market, a trader could buy in the cash market, sell in futures and pocket the difference.

Today, the yield is down to 2 percent at best and even that is quickly evaporating — thanks in part to the advent of algorithmic trading. Jiten Chheda who runs the place saw the writing on the wall and has since diversified into providing wealth management services and even a retail store for sport and wellness goods. He reckons time’s up for the 10,000-odd jobbers in Mumbai alone — and the 5,000 others that dot the rest of the country.

“Only creative people will have something to do in the financial markets,” Vasant Dhar tells me. A former quant guy at Morgan Stanley, he now heads the information systems group at Stern University in New York.

I wonder if there’s anybody out there who believes India will remain insulated from algorithms and end up talking to Tridip Pathak. He is a senior fund manager at IDFC and argues algorithms look for correlations based on past data. The Indian markets, however, are still evolving and placing too much emphasis on the past won’t work. “Liquidity, business models, and even the numbers of market participants keep changing. How can algorithms work effectively in this environment?” he asks me.

Infographics: Vidyanand Kamat

It is an interesting argument, but given my proclivities, not one I am entirely convinced about. I believe that when an event keeps recurring, it generates more frequent data and eventually helps in narrowing spreads even as volumes go higher. To figure out if I’m on the right track, I turned my attention to Superfund. I’d like to think of them as a hedge fund, though that’s not how they see themselves. I guess that’s because Superfund allows investors with as little as $5,000 to buy into its various funds. To get the attention of any other hedge fund, you’ll need at least half a million dollars.

While it hasn’t started investing in India yet, it has set up shop to collect past market data from India to tweak its algorithms for local conditions. Superfund manages absolute returns strategies and operates out of 150 countries. In 2008, when the world spiralled into a recession, the various funds it manages delivered returns in the region of 35-70 percent.

Consider the Superfund Gold Equity Neutral Strategy Fund for instance. For 2010, it is up 30 percent and over the last three years, it has delivered average returns in the region of 33 percent. What this fund does is, it goes long on selected stocks from a universe of 2,500 companies around the world even as it goes short on the index. Since the entire portfolio is dollar denominated, the currency is hedged by investing in gold.

I asked its CEO Aaron Smith how they managed. “Systematic trading is very scientific and algorithms don’t need to be tweaked all the time,” he said. “It is only when a fund takes extremely short positions that the system needs to be updated on a regular basis.”

Not surprisingly, over the last decade, quant trading algorithms have become very popular with most hedge funds. There’s Renaissance Technologies that manages about $30 billion. All it does is hire quantitative analysts to build mathematical models to look for new ways to make money by investing into financial markets across the world. To get a sense of how successful they’ve been, consider this number. James Simon, the 70-year-old mathematical genius who heads Renaissance ranks 55 on the Forbes billionaire list. I rest my case.

My limited point in all of this is that with such huge upsides, it is inevitable that market participants start adopting the technology. The people at National Stock Exchange (NSE) tell me quite a few prop shops have set up operations in India. These are trading groups that usually trade electronically at a physical facility. Prop shops supply their traders with education and capital resources to engage in a large number of deals each day. For various reasons though, they declined to direct me to these participants.

Think of it as an arms race. Once one brokerage has it, others will have to buy it just to remain competitive. “Initially, the payback on investments in technology will come by way capturing momentary pricing imperfections in the market and substituting manual trades by machine-generated trades,” says Anup Bagchi, executive director at ICICI Securities. “But later, the marginal utility of this investment will start to fall as the market becomes more efficient,” he explains. That, in turn, will compel brokerages to go out and buy more sophisticated software. Yes, it is expensive. But that’s a cost broking firms will have to live with.

As Motilal Oswal of Motilal Oswal Securities puts it: “It will improve productivity and create more opportunities.” Then there is also the fact that the cost of trading in India is 30 times that in other parts of the world. A lot of this cost can be trimmed with better technology.

Then there are the stock exchanges itself that want more Indians to take to algorithmic trading. There’s a very simple reason why. Like I said earlier, it increases liquidity in the market and consequently reduces the cost of executing a transaction on the stock — also known as the impact cost. Right now, the impact cost for major indices in India is around 0.06 percent, twice the costs in the West and markets like Singapore and Hong Kong.

At the NSE, investors can opt for co-location facilities. This means, they can place their servers very close to that owned by the exchange in return for a fee — in this case, Rs. 20 lakh per rack plus an additional annual fee of Rs. 2.5 lakh. Why, you may wonder, have 70 members already opted for this? It’s because when your trade is powered by algorithms, every millisecond counts. And the closer you are to the exchange’s servers, the faster your order gets executed. If a trader operates via V-Sat, it takes 700 milliseconds for the order to hit the system. As against this, a leased line to the exchange can deliver the order in 40 milliseconds. But with co-location, a trader can beat this time as well. Evidently, there are more takers queuing up. Ramesh Padmanabhan, CEO, NSE.IT, says demand for his algorithmic software products is growing.

And if anymore clinching evidence is needed that we’re headed the algorithmic trading route, consider this. Practically all of the cash futures arbitrage market is dead — one of the other reasons why Jiten Chheda of whom I spoke earlier is diversifying. The opportunity now lies in futures and options. For as long as I can remember, traders liked to stick with stock futures, forget even index futures and options.

It has taken a while to build volumes in the options market. But as opportunities in other markets diminish and algorithms get into the picture, traders have started to look at options positively. In fact, the best opportunities in the Indian market right now are index options. In fact, for the first time in July this year, index options accounted for 57 percent of the total derivatives turnover on the NSE. I think this is great news because the options market is best operated by algorithms.

Am I being too effusive here? Perhaps not! It’s just that the pros outweigh the cons. Sure, I haven’t spoken of the cons yet and maybe I ought to talk of the downsides as well. Well actually, downside isn’t quite the word I’m looking at — speed bumps would be more like it I guess. And what would they be?

There is a simple rule to financial markets. As they become efficient, alpha seekers — simply put, those who will employ every trick in the book including algorithmic trading to beat the market — will have an increasingly tougher time. In situations like these, investors need to trade really fast to take advantage of the millisecond anomalies that exist in the market. This leaves them with little option but to go for high frequency trading (HFT). But this involves two costs: Expensive hardware and the cost incurred in getting their servers closer to that of the exchange to reduce latency. As demand for these services grow, I suspect the prices of real estate to house servers near the exchange will go up significantly. In fact, I’d argue the Rs. 20 odd-lakh NSE charges right now is peanuts.

My colleagues Liz Moyer and Emily Lambert reported last year in the US edition of Forbes that in Chicago, six square feet of space in the data centre where the big exchanges house their computers goes for $2,000 a month. And that it is not unusual for trading firms to spend 100 times that to house their servers. So much so that even the tradition bound NYSE plans to open a 400,000 square feet tech centre in New Jersey and is taking orders for server stalls.

Then there is that niggling issue of Securities Transaction Tax (STT) at 12.5 percent on short-term transactions. This can saddle costs and make things murky if the economics don’t work out.

Doubts exist as well on whether Indian exchanges are capable of handling volumes generated by HFT because not all of these transactions are legitimate and convert into actual trades.

At NSE, the order to trade ratio exchange authorities are willing to tolerate right now is 7:1. Which means, on the outside, for seven orders generated and only one trade actually goes through, they won’t utter a peep. The moment this ratio is breached, they begin to get uncomfortable. If I were to compare this number to what exists in other markets, the ratio is in the region of 14:1. The latter is the kind of environment that’s more conducive to HFT.

When I raised this with an NSE official, he said the order to trade ratio and capacity are two different issues. He claims it isn’t that NSE cannot handle increased volumes, but that NSE likes to play safe. “In some cases if 1,000 orders are punched and only two are executed, in all likelihood there is a problem and we need to step in for the sake of market safety,”

he says.

And finally, there is the fact that it takes a long time for some relationships to give way. Recently, NSE decided to offer a direct market access (DMA) tool to the mutual fund industry. This would allow funds to send their orders directly to the exchange. It’s the kind of tool that is critical to HFT taking off, because once again, it plays a significant role in reducing the time an investor takes to get to the market.

Mutual funds prefer to keep their trades private. This is because if word gets out in the market that a particular fund house is looking to buy a stock, for obvious reasons, prices of that stock will go up. It’s a practice called front running by those with insider information. Eventually, unit holders in the fund have to bear the brunt.

Which is why, mutual funds can pass only 5 percent of their trades through a single broker. With DMA on their side, theoretically, mutual funds ought to have two things going for them. They get to the market fast, and they reduce the probability of front running. But things haven’t worked that way yet — in large part because mutual funds don’t want to sever ties with brokers yet.

That said, I see all of these as minor irritants. All of it will have to give way to technology as it comes by. I will concede one thing though. There are times when there is simply not enough data for computers to process and do anything about a situation. That’s when the only thing that can work is a brain made of protoplasm, which incidentally, is the subject matter of the graphic novel story that follows on the next page.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)