Credit where due: Startups solving the rural banking problem

Despite the strides made by Jan Dhan Yojana, last mile connectivity continues to pose a problem for rural banking; new ventures are trying to solve that by leveraging technology and partnerships

A significant number of beneficiaries of rural MFIs turn out to be women, who form a large part of the agrarian workforce

A significant number of beneficiaries of rural MFIs turn out to be women, who form a large part of the agrarian workforceImage: Biswaranjan Rout/ Nurphoto via Getty Images

Tall, slender and all of 26, Vennila Ganesan emerges from her concrete hut, two toddlers in tow. Behind her, a row of similar, white-walled huts stretch into the distance. Goats graze nearby; a stray dog follows them about.

Here in Kanurpudur, a village km north of Coimbatore, the sun shimmers but a crisp breeze is in the air. Ganesan, dressed in a pink, printed nighty with a dupatta neatly pinned on either shoulder, has just returned from a day in the sugarcane fields nearby, pocketing ₹250 for the day. She took a loan of ₹25,000 from Samasta, a micro finance institution (MFI) with outposts in the area, about two years ago, and bought eight baby goats. Later this year she plans to sell the goats at a ₹20,000 profit. “It will help me take care of my children,” she says. “Especially in the [summer] months when there is no agricultural work.”

Asked if she uses her bank account regularly, she lifts her hand to her mouth to hide a giggle and shakes her head in denial. “I opened it years ago to get the government subsidy for the birth of my first child,” she says. Since then she has only used it when necessary; when she had to access Samasta’s monies that were credited to her account. Or to take care of the monthly interest payments that are directly debited from her account, in which case she makes the three-hour long trek to the closest bank branch—compromising on a day’s wages—to deposit just enough money.

Ganesan’s ordeal is not uncommon. The Jan Dhan Yojana scheme, launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014, aimed to provide every Indian household with a bank account by 2018. The account-opening spree saw adults with bank accounts jump from 53 percent in 2014 to 80 percent in 2017, according to the World Bank. But that hasn’t translated into meaningful financial inclusion, especially for rural, low-income populations. Bank branches are long distances away, form-filling is tedious because of low levels of literacy and distrust of financial institutions runs deep. Besides, most low-income families transact in cash and prefer to store their savings where it’s easily accessible.

In a country so vast it’s difficult to build the physical infrastructure—brick-and-mortar bank branches, ATMs and banking correspondents—to service rural, low-income families. “India has made a lot of progress in the past two decades but there is more work to be done,” says Gregory Chen, lead financial sector specialist at the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP), a think-tank housed at the World Bank. He points out how the country has moved past its over-reliance on a few state-owned banks to a more diverse, private sector driven financial system. This includes the opening up of small finance banks as also payments banks that let customers make deposits, transfer money, and pay utility bills through outposts at local kirana stores. But these are yet to penetrate rural India, in places like Ganesan’s village.

Moreover, innovations in digital payments that run on UPI, the interbank money transfer system launched by the government in 2016, have led to a spurt in the number of payments providers. But in the absence of sufficient cash-in and cash-out points in the hinterland, people will not shift to digital money, says Chen.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

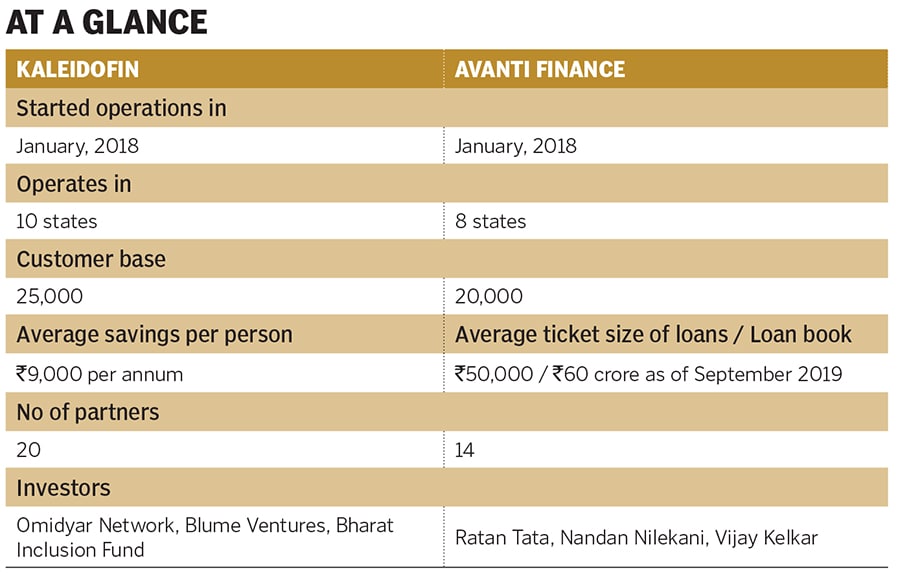

Sucharita Mukherjee (left), Kaleidofin: Providing tailored financial solutions for customers

Sucharita Mukherjee (left), Kaleidofin: Providing tailored financial solutions for customers Rahul Gupta, Avanti Finance: Solving a “population-scale issue in a population-scale manner”

Rahul Gupta, Avanti Finance: Solving a “population-scale issue in a population-scale manner”