For The Love of Reading

Children from poor backgrounds don’t have access to good books. One man in Bangalore is changing that with his ever growing network of libraries

A little over a decade ago, if anyone had told Vimala and Umesh Malhotra that their mission in life would be to set up libraries for children, they would probably have laughed. But then, they wouldn’t have accounted for boredom.

The Malhotras were a typical IT couple and had just moved back to Bangalore in 1999 with their four-year-old son Tarutr, after nearly eight years at Infosys in California. But little Tarutr was bored. What he and his mother missed the most was a good library. Vimala says, “We used to go to the library for my son, and it had so many activities; back in India, the lack of a good library where children could have their space, where no one tells them to keep quiet, and it is their hangout zone was lacking.”

That got her thinking about setting up a library.

Meanwhile, Umesh Malhotra had started an IT company of his own, called Bangalore Labs, along with four other promoters. But he too was soon weary of it and sold his stake in 2002. After he quit, there were many job offers but this time he wanted to make sure he was heading in the right direction.

“I waited nine months. I thought, let me think through what I want to do in life. My wife wanted to start a library and I said okay, I think I can be the project manager, and that began in March, 2003.”

Their brainchild was called Hippocampus, named after the part of the brain associated with learning and memory. It was set up in Koramangala, Bangalore.

Hippocampus is not just a library. It is, as Vimala imagined it, a kids’ hangout zone. Children can sit in corners reading a book; they can sign up for various activities like painting, aero modelling, carpentry or sign up for a science club. In fact, it is these activities that engage the child’s interest that has made the library a success.

Seven years later, the numbers vouch for that — membership grows at 60 children every month with a membership base of 3,000 children.

Umesh Malhotra wanted to do more. “We created a great space for urban kids, but what is happening in the slums of Bangalore?” he says.

He started meeting government schools and development sector workers to understand why they did not have or even think of having a library. “In many ways I started advocating it.”

While they all acknowledged the need for a library, they grappled with how to get children to read. Children do not read anymore, they said, but Malhotra knew better.

His initial response though, was to give money to people to help buy books and run libraries in the slums. Big mistake!

“The two or three people we had given money to, their libraries never worked because they were always giving us excuses, ‘you know children are not interested; I can’t find someone

to run a library’, and I thought, come on, I just spent Rs. 40,000 on a library and you are giving me these excuses,” says Malhotra.

He knew he could not do this on his own, and he knew the model had to be tested. What worked for a city library may not work for a government school library. For one, reading abilities were different and an English books-based library may not work. So he partnered with the Akshara Foundation, which was internally discussing the same issue: The need for libraries in government schools.

In their trial-and-error testing period between 2004 and 2006, they built 52 libraries around Bangalore. And in the process, found a model that could work for government schools.

This model has three arms: Hippocampus, the parent library, runs for profit; Hippocampus Reading Foundation (HRF) focusses on government schools in cities and the rural areas; and a Book Council sorts through content from various publishers and drafts catalogues for urban poor, and rural children.

HRF sets up libraries by partnering with local NGOs, who finance and maintain these libraries. A government school teacher runs the library; children pay a membership fee of Rs. 10 per month. However, in most cases the partner NGO funds the librarian’s fee as well. “The initial cost of setting up a library is Rs. 10,000 and then per year, the cost for getting new books is approximately Rs. 3,000,” says Maitreyee Kumar, founder, Dream School Foundation, which has set up 10 libraries in partnership with HRF.

For Hippocampus, the Malhotras had gone through a list of 20,000 titles to choose 3,000 which they ordered from the US. But for HRF, they needed to localise the content. That’s where the Book Council came in. Vimala, along with her colleague, Arvinda Anantharaman had the task of organising a catalogue of books for government school children.

“For a language like English you have a library list of anywhere upwards of 20,000 titles across different genres. We would be lucky if we even had 800 Kannada story books to choose from. Right now, we only have 300 Kannada books available through various publishers,” says Vimala. So far, they have hand-picked 150 books per library across six levels.

Each level has approximately 10 to 12 books. Even so, four books in every set of 12 tend to go out of publishing at some point. This is something they constantly have to work on for the HRF programme.

The books are matched to the children’s reading levels which are graded under a colour coding system called GROW BY Reading (GBR). The acronym GROW BY stands for green, red, orange, white, blue, and yellow — green is the lowest level and yellow the highest. GBR also creates activities around the books that take the children beyond the content in the book. For example, they make animal masks based on a book they read on animals or discuss issues raised in the books.

In the urban poor areas, these libraries are already making a difference. Children’s reading levels are up between 30 and 70 percent. The partnership with Akshara Foundation has now ended, but the Foundation has set up 1,410 libraries across Karnataka based on what it learned through the initial exercise together. HRF, on its part has added 150-odd libraries to the initial 52. Its catalogue is now available for books in five languages (Kannada, Tamil, Urdu, English and Hindi). It is also trying to enlist corporates like Cisco and ArcelorMittal as sponsors.

Now, Malhotra wants to expand the library network to rural areas. That idea took shape in January 2009 after he met D.M. Sridhar, governing board member, Grama — an NGO that works on issues of employment and microfinance. Sridhar had heard of HRF’s work with government schools and suggested Malhotra work with rural schools as well.

Sridhar’s experience with local self help groups has helped Malhotra develop a slightly different model that will get the rural community actively involved in running a children’s library.

Both are clear that the rural model has to be a micro-enterprise solution.

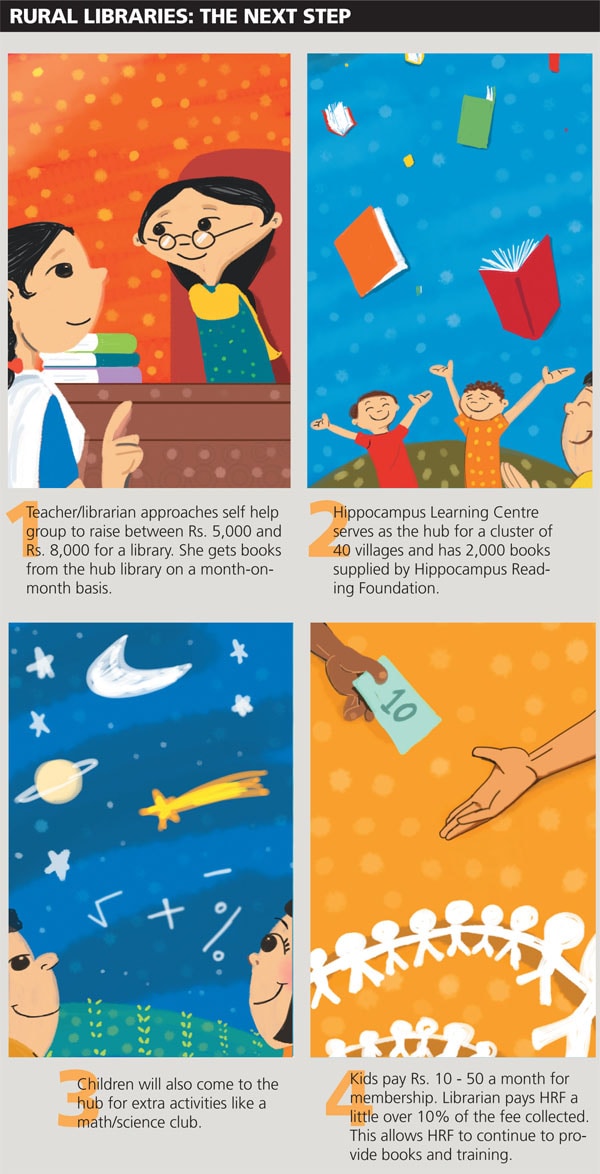

The librarian — someone from the village — “owns” the library. She raises Rs. 5,000 from a self help group to set it up in her own home, or in a room given by the panchayat. She gets 150 books in the GBR catalogue and HRF trains her. Like in the government school model, the child pays a membership fee of Rs. 10 a month. This will help the librarian break even within 18 months.

“Many of [the villagers] do not want to leave their village, and this position gives them the role of a teacher, which means respect,” says Malhotra.

Two women in the Chitradurga district in North Karnataka tried this model in July, 2009. Saranamma, in Bosadevarahatti, saw her start-up organisation receive 70 members. In three months, she was back asking for more — she wanted computers.

Illustration: Abhijeet Kini

This sent Malhotra back to the drawing board, as it would be impractical to provide a computer for each library. HRF is now working on a model that will include an education centre — the Hippocampus Learning Center (HLC), which, unlike HRF, will be a for-profit organisation. This will be a place where children can spend time after school hours; they can read, draw, colour, learn and use a computer. It will serve as a hub for a cluster of 40 villages, each with their own libraries. However, this will cost the librarian and the children a little more.

Malhotra expects a fee to be charged to the librarian. She will pay HRF a little over 10 percent of the fee collected from the children after an initial three month period. This will help HRF recover the cost invested into the programme and help it continue providing material, training, and books. Malhotra believes that by doing so, you shift the cost of ownership to the librarian and this will drive the way she performs. That, he says is a lesson drawn from having put Rs. 40,000 of his own money into the urban government schools library project, only to have people give him excuses why libraries did not work.

He claims an initial investment of Rs. 1.4 crore through angel investors, and is confident that the initiative will pay off. He has nine people on the ground in the Mandya and Davangere districts of Karnataka. Their sole purpose is to advocate the cause for a community library. Malhotra expects to have 20 libraries by September this year, and expects that number to grow to 2,000 in three years.

Kumaraswamy C., who used to work with Prakruti, an organisation that partnered with HRF, says, “[HRF] is used to promoting informal self-learning, and this has been received well by the community as they see it as a community managed centre, and not something outsiders set up.”

But not everyone is comfortable with the idea of HRF charging the librarian a fee. Development workers on the ground say that any initiative in the rural sector can work only when it is run by the people and for the people. A fee like this still has the feel of an outsider in the village.

Sridhar too differs with Umesh on this point. “Right now, there is no understanding to have a payment. This is supposed to work on a self-scalable model. There should be no financial involvement of Grama or HRF.”

As the library network grows, another issue HRF will face is planning, says Sangeetha Menon, fund raiser, HRF. To build scale, HRF needs to be able to transplant a templatised model for each new library. But each locality presents its own unique problems that require customisation, which could slow down the roll-out. For example, “In one government school, the NGO came back to us and said the content in our books placed too much importance on the mother. Most children in that school, for some reason, did not have mothers, and so we changed the book list for that school,” says Menon.

Also, though HRF has a catalogue of books in five languages, not many children’s books are available in languages like Oriya or Bengali. So, setting up libraries in such states will be a challenge.

Malhotra is aware that the ground they have to cover is large. “I have learned an immense amount of patience since we started HRF,” he says.

He may have to hold on to his patience to see HRF’s goals through in India, but recently he got some encouragement that his chosen path can make a difference. Room to Read, a global NGO that has some 10,000 libraries across Nepal, Sri Lanka, Cambodia and Vietnam, invited HRF to train their librarians in Cambodia on how to engage the child, and techniques of running a good library.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)