China's Oldest and Biggest Winery Looks to the Future

China's biggest winemaker draws on a storied history to plot its future

On a gentle slope, parallel trestles of vines lead up to a lofty European-style house, one of several self-styled châteaus in coastal Shandong, the biggest wine-producing region in China. Thick bunches of Riesling and Cabernet Gernischt grapes ripen under a hazy summer sky. Built in 2002, Chateau Changyu-Castel is run by China’s bestselling winemaker, Changyu Pioneer Wine of Yantai. Here a storied past meets ambitious plans to stay atop China’s burgeoning wine market.

Changyu enjoys the kinds of rising gross margins that global winemakers can only dream of—79 percent in 2011 on sales of 90,000 tons of red and white wine, its main product line, plus brandy, sparkling wine and Chinese “health liquor.” Changyu’s net rose 33 percent to $303 million on revenues of $918 million, up 21 percent and tripling in five years. It appears for a seventh yearÑfifth con- secutivelyÑon Forbes Asia’s Best Under A Billion list.

As with domestic rivals like Great Wall and Dynasty Fine Wines, the bulk of Changyu’s revenues derive from sales of cheap red wine. For all the talk of fine wines conquering China, the mass market remains a sea of plonk. In 2010, 72 percent of wines retailed for less than $5 a bottle, according to Access Asia, a consultancy in Shanghai. In most cities grape wine comes a distant second after rice wine, or baijiu, as the toast of choice at banquets. Only 1.3 percent by volume was priced over $10 in 2010.

Changyu has its eyes on this premium category, which has been stoked by wealthy buyers of fancy imported wines. Joint ventures like Chateau Changyu-Castel, in which France’s Castel Group holds a minority share, and estate wineries in other provinces offer a way for Changyu to improve quality and reposition the brand, possibly for even higher margins. The company has quietly acquired vineyards in Italy, Canada and New Zealand without the attention paid to Chinese purchases of trophy châteaus in Bordeaux.

“We try to raise our reputation at the high end, while at the same time we’re marketing wine as a product for ordinary people,” says Zhou Hongjiang, the company’s general manager. “We’re trying to develop in both directions.”

Changyu, like many Chinese wineries, can produce only so much table wine from the country’s limited vineyard capacity and needs juice from abroad, as well as the already bottled imports, to build out its desired dual market.

Zhou’s team plans to open hundreds of wine stores across China, where it will sell its branded wines and those of foreign partners who grant exclusive import and distribution rights to Changyu. Within six years Changyu plans to open 3,000 stores, including franchises. It says that it will prevent counterfeit wines from being sold, always a concern here.

Last year sales of imported wines, including Changyu-in- vested wines, accounted for less than 1 percent of company revenues. But Sun Jian, vice-general manager, who is in charge of negotiating import rights, says that sales of imported wines have already doubled so far this year, even before any partnerships are inked (he declined to name any candidates). “In the future it’s likely that the share of imported wine will continue to grow. The trend is clear. Changyu, as a distributor, sees an opportunity to provide what our customers want,” he says.

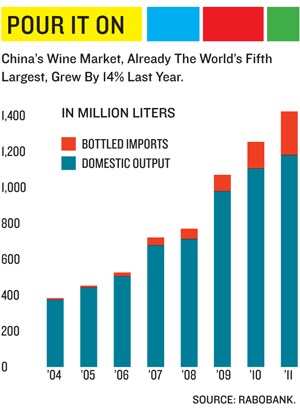

These are steps into highly fragmented territory. Last year Chinese customs counted 3,863 importers, up 200 percent in five years, according to Rabobank, a Dutch bank specialising in the sector. Many bypass retail channels and rely instead on direct sales to wine-quaffing banqueters who want to impress guests. Importer markups on bottled wine can be as much as three-fold, say trade experts.

Changyu officials say that the company’s distribution network and market knowledge make it a more suitable sales agent for major foreign wineries that want to build their brand in China. “We’ve talked to [potential] partners. They see Changyu as a heavyweight player in this market,” Sun says. COFCO, the state-owned food giant that controls China Great Wall Wine, also markets imported wines.

Changyu has other grand plans. To celebrate the company’s 120th anniversary it has earmarked nearly $1 billion over four years to create an international “winetropolis” in Yantai, where a few million residents sprawl between ocean and farmlands. Included will be a research institute, another château, a wine trading centre and a tourist town complete with hotels, a mu- seum and, naturally, bars. Officials say the project will be financed from retained profits and is on top of $300 million in capital expenditure in 2012.

It’s a far cry from Changyu’s roots as China’s first modern winery. Its founder was Zhang Bishi, or Cheong Fatt-Tze, a Cantonese businessman who made his fortune in Southeast Asia. From his base in Penang, where his mansion is now a boutique hotel, Zhang built a trading empire in Indonesia, Malaysia and China, and was dubbed “China’s Rockefeller” by the New York Times in 1915, a year before his death. By then he had thrown his support behind Sun Yat-sen, taking up an appointed position in the republican assembly after the fall of the Qing dynasty.

In 1892 Zhang founded Chang Yu Pioneer Wine near the thriving treaty port in Yantai, or Chefoo. The wines were sold mostly to foreigners in China or shipped overseas. The company’s museum, built on the original winery site, displays a medal awarded at a 1915 international expo held in California.

By the early 1930s Changyu had fallen on hard times. It was nationalised after failing to repay loans to the Bank of China. Ownership passed in 1949 to the People’s Republic of China. Under Maoist rule bourgeois wineries stagnated. However, state-owned Changyu received a capital injection in 1954, and wines were served to foreign dignitaries in Beijing. That tradition has con-tinued as Barack Obama and other world leaders make state visits.

China’s wine consumption revived in the 1980s, and Changyu became the first wine company to list its shares in Shenzhen in 1997. In 2005 the city government sold a 33 percent stake in Changyu’s parent company, Yantai Changyu Group, to part of an Italian liquor company. An additional 10 percent was divested in the same year to the World Bank’s International Finance Corp. The parent company is controlled by a series of holding firms in which senior management holds minority stakes. Sun Liqiang, chairman and CEO, is the parent’s legal representative on the listed Changyu’s board.

Yantai remains its largest production centre in China. Great Wall and Dynasty also have vineyards there, but it’s considered home turf at Changyu. “In this area we are definitely domi- nant,” Zhou, 48, tells Forbes Asia, before leaving for a ten- day marketing trip in southwest China. A Chinese MBA who started at Changyu as a management trainee, he’s held his post for 11 years and is tipped to succeed CEO Sun eventually.

So far wine consumption in coastal cities in China far outpaces that of cities farther inland, evinced by Changyu’s territorial breakdown of sales. In 2011, 85 percent of its revenues came from the eastern seaboard. But China’s overall wine consumption is hard to track, says Edward Ragg, cofounder of Dragon Phoenix Wine Consulting in Beijing. “There’s a massive scramble to get into the second-tier cities and beyond that.”

Winemakers are vulnerable to any sharp contraction in consumer spending as China’s economy decelerates. A surge of wine imports in late 2011 appears to have dampened shipments of domestic wine sales in the first half of the year.

This could make it harder for Changyu to hit its sales target of 9.5 percent growth. Its stock is down sharply this year after a big dividend payout in June. Hong Kong-listed Dynasty has also seen a dive.

Sun Jian admits that growth suffered in the first quarter but insists that sales of wine and other drinks have since picked up. “I think the rest of the year will see an improvement,” says Sun, 46, who started out planting vines as a 23-year-old intern. Up to 90 percent of wine sold in China is for gifts or served at banquets for business and political elites. Periodic orders to party cadre to curb excesses usually fall on luxury brands of baijiu. “When you do business, to show respect you have to drink a product with a certain value. If baijiu is banned, grape wine is a good alternative,” says Martin Wu, agribusiness ana lyst at Rabobank in Shanghai.

Changyu’s premium wines are not for the parsimonious. A 2005 Cabernet Sauvignon from its estate outside Beijing retails for $95, which puts it in a category with a bottle of decent Bordeaux. At the château in Yantai tourists are led down into a cellar past rows of imported oak barrels. Upstairs a small bottling unit and 20-ton fermentation vats can be viewed from a glassed-in balcony. The impression is more of wine-themed tourism than serious viniculture. But it allows Changyu to present itself as a pre- mium brand in a market that is still in its infancy. “We want to take the next step forward,” says Sun.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)