Wine, whisky, watches: Does your investment portfolio have passion purchases?

In an atmosphere of uncertainty and being locked down, luxury collectibles provide an option to invest as well as indulge in things that bring joy

Image: Shutterstock

Image: ShutterstockEarly last month, a British resident sold Macallan whisky bottles gifted to him by his father over 28 birthdays, and with the money put down a deposit for a house. Closer home, a couple of years ago, a collector of rare whiskies sold six bottles from his collection, the proceeds of which paid for his son’s wedding expenses. And at a Sotheby’s auction in March this year, a bottle of Karuizawa 52 Year Old Cask #5627 Zodiac Rat 1960—bought in 2013 for £12000—went for £363,000, a whopping annual return of 418 percent.

You win some, you lose some. Dillon Bhatt, head of international business development at investment consulting firm Millwood Kane International, started collecting watches as a hobby and then realised it was a great tool for long-term investment. He recollects a Patek Philippe he was looking to buy in 2017, a special, limited-edition anniversary model that was first released in September 2016. “In January it was around 120,000 euros and I was negotiating around 140,000 in April 2017. So within the first three to four months, there was an appreciation of 20,000 euros. I didn’t buy that watch, and now, in 2020, it is valued at over 300,000 euros.”

Passion investments typically involve the owning of assets like classic cars, handbags, watches, art and whisky. Their prices move independently of other asset classes, and the Knight Frank Luxury Investment Index provides an indication of the most coveted objects of desire each year, as well as tracks the performance of a theoretical basket of selected collectable asset classes using existing third-party indices. But the buying and selling does gain traction during an economic downturn—people sometimes have to liquidate their possessions to raise capital, which then throws up opportunities for others to pick up pieces that otherwise might not have become available, or at better prices.

Take the art market, for instance, which industry experts point out has seen newer heights in pricing amid a raging pandemic’s shadow on the economy. “When economies are weak, you see a number of auctions enter the market. Where India is concerned, we have only two references, one in 2009 and one now, but in the Western market we have seen this happen on several occasions,” says Arvind Vijaymohan, chief executive of Artery India, an art market intelligence and asset advisory firm, that manages the art investment holdings of a select set of high net-worth Indian families. The Indian art market, he says, is following a relatively predictable route, aligned to that of the comparatively more evolved global economies where this asset class has a wider range of patronage from the investor and connoisseur circles. “Particularly in the past four months, there has been a high level of trade in the auction market.”

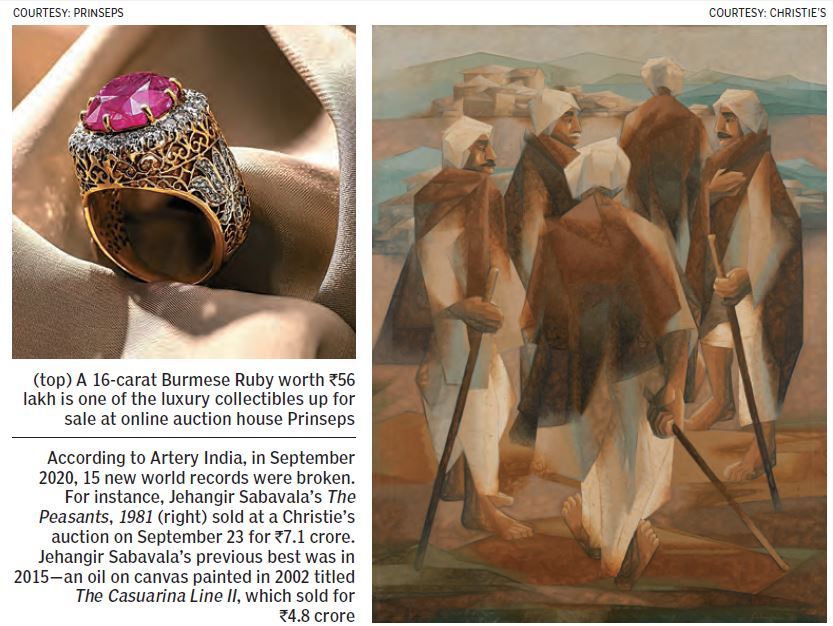

Founder-director of online auction house Prinseps, Indrajit Chatterjee, concurs. “As a collector, if you see a new art work that has come up that you have been waiting for 10 to 15 years, at that point you’re not calculating the value. You just want it. And, that is very obvious in the current art market where new records of artists have been made.”

According to Artery India, from January to August this year, the turnover was ₹301.4 crore, achieved from the sale of 1,131 works—57 amongst these sold for above ₹1 crore. A total of 316 artists’ works were featured, with new global price records for 68 amongst them. From January to August 2019, the turnover was comparatively higher at ₹442.4 crore, but this was achieved from the sale of a commensurately higher number of works: 1,503 in all. The number of works that sold for above ₹1 crore was also similarly higher, at least 77 works. The works of 410 artists were featured, with new global price records for 60 amongst them.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)