What caused the Mistry-Tata split

The acrimonious power struggle between the ousted Cyrus Mistry and the Tata Group raises questions about corporate governance

Image: Sameer Joshi / Fotocorp

Cyrus Mistry (left), who was removed from his post as chairman of Tata Sons, seen in this file picture with Ratan Tata who has taken over as interim chairman

The festive season of Diwali saw fireworks of a different kind playing out at Bombay House, the headquarters of the $103 billion-Tata Group; and not the kind that brings light and joy all around. The combustion is a potential hazard for many, including the ordinary shareholder of Tata firms.

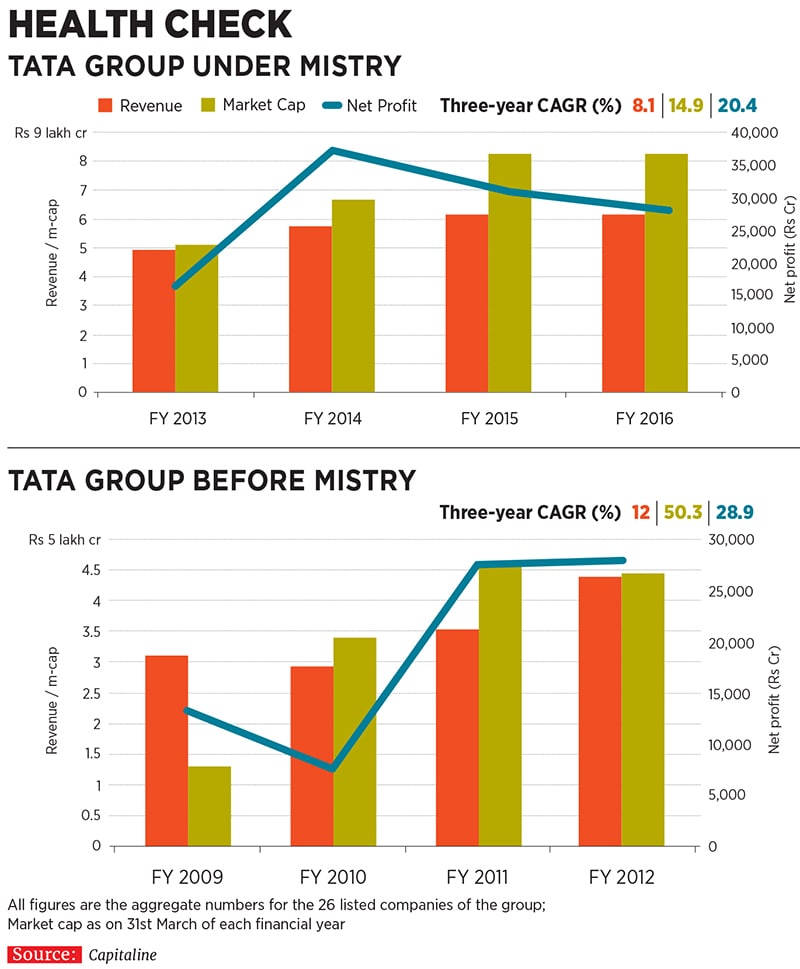

Less than four years after Cyrus Mistry, 50, was appointed chairman of the salt-to-software group, the board of Tata Sons, the flagship holding company of the conglomerate, voted to remove him in a meeting held on October 24. The proposal to replace Mistry was largely at the behest of the Tata Trusts, the charitable bodies that own a 66 percent stake in Tata Sons and whose chairman is Ratan Tata, Mistry’s 78-year-old predecessor.

Tata, who led the group for over two decades, hung up his boots at Tata Sons in December 2012 and passed on the baton to Mistry, son of Pallonji Mistry, whose family is the largest outside shareholder in Tata Sons with an 18.4 percent stake.

But what seemed like a robust succession plan has gone sour. Tata is back as interim chairman and will hold fort for four months, in which time a selection committee will choose Mistry’s successor. He has reconstituted the management structure, retaining three members from Mistry’s now-disbanded Group Executive Council (GEC)—Mukund Rajan will continue to be responsible for ethics and sustainability, with the additional responsibility of overseeing the operations of the overseas representative offices of Tata Sons in the US, Singapore, Dubai and China; Harish Bhat, in addition to marketing and customer centricity, will also manage the Tata brand and, for the time being, oversee the strategy and business development functions while Gopichand Katragadda retains his post as the group’s chief technology officer.

Tata Trusts, the principal shareholders of Tata Sons, justified the move on the grounds that Mistry had “overwhelmingly lost the confidence” of members of Tata Sons’ board of directors, on account of “repeated departures from the culture and ethos of the group”.

Mistry was having none of that. In a letter addressed to Tata Sons’ directors and members of the Tata Trusts, he wrote that he was “shocked beyond words at what had transpired”, and at the treatment meted out to him. While the board of directors of a company is well within its right to vote a chairman out of power, what surprised onlookers was the way in which Mistry was removed; and the swiftness with which his profile as group chairman, and associated content like an in-house interview, were taken down from the website (the interview has been uploaded again in the section on former chairmen of the group).

The resolution to replace Mistry as chairman was not specified as a standalone item in the agenda of the board meeting on October 24 and was brought up for discussion as a part of the ‘other items’ that are usually reserved for discussion last.

“The way the board behaved was surprising,” says Anil Singhvi, founder of proxy advisory firm Institutional Investor Advisory Services. “Mistry should have been given adequate time to put his case before the board at least.”

Following his ouster, the former chairman outlined the various operational difficulties he faced while discharging his duties and pointed to an alleged lack of corporate governance at the group. Foremost among his complaints was that a free hand to run the operations of the group—which was promised to him when taking over this job—was never given to him. This resulted from a wrong interpretation of the Articles of Association (AoA) of Tata Sons, which “changed the rules of engagement” between Tata Trusts, Tata Sons, different operating companies within the group and himself, Mistry said in his letter.

A subsequent statement from Tata Sons called Mistry’s claims as “unsubstantiated” and allegations as “malicious”.

Explaining the change effected in the AoA of Tata Sons, a source close to Ratan Tata points out that over the years, there was a deliberate overlap created between people manning Tata Trusts, Tata Sons and group companies. This was to ensure synergy in the thought process across the spectrum, aimed at creating overall shareholder value. For instance, many senior Tata Group executives like RK Krishna Kumar (former vice chairman of Tata Global Beverages) and Noshir A Soonawala (former vice chairman of Tata Sons) have been directors on the board of Tata Sons in the past.

At the time of Mistry’s appointment, that chain was being broken for the first time, the source says. While he was the chairman of Tata Sons and various group operating companies, he didn’t hold that position at Tata Trusts which utilise dividends received from Tata Sons for various philanthropic activities. Also, till recently, the only other Tata insider on the Tata Sons board, apart from Mistry, was finance director Ishaat Hussain.

“Mr Tata had made it clear that because the chain was breaking for the first time in decades, there needed to be a way to institutionalise this synergy,” this source says. “It was with this intent that the AoA was changed to state that items that require approval of the Tata Sons board, like annual business plans, must have the affirmative vote of the directors nominated by the trust (comprising one-third of the Tata Sons board). This doesn’t translate into an intention to interfere in the management of any enterprise.”

However, a source close to Mistry claims that the change in the AoA was misinterpreted to imply that some of the important items meant for discussion at Tata Sons board meetings had to be run by the trustees first. “This was slowing down decision-making and leading to confusion regarding Mistry’s role as chairman of Tata Sons, vis-a-vis his role as chairman of various group companies,” this person says. Consequently, Mistry circulated a note on the ideal governance structure for the conglomerate that outlined proposed roles of all stakeholders, for discussion at the board meeting in which he was replaced. But this wasn’t considered, claims the person with direct knowledge of Mistry’s version of events.

Harsh Mariwala, chairman of FMCG maker Marico, says the dynamics of the relationship between the incoming chairman at Tata Sons, his predecessor and other stakeholders should have been better codified to avoid divergent interpretations. This is something that he had done in Marico when he handed over the day-to-day responsibilities of running the company to Saugata Gupta, its MD and CEO. “There should have been a clear list of dos and don’ts that should have been agreed upon, in writing, such as what decisions he can take independently and those he cannot,” says Mariwala.

Both camps agree that the relationship between Mistry and the trustees, led by Tata, had begun on a cordial note when Mistry took over, but a mutual trust deficit built up and intensified over the last year.

An example of this is Tata Power’s acquisition of Welspun Energy’s renewable power assets. Sources close to Tata say Tata Power’s management, led by Mistry as its chairman, intimated the Tata Sons board about the deal too late and well after it had been struck. “Nobody questioned the merit of the transaction. But the very fact that the major shareholders weren’t aware of the details of a major deal was uncalled for,” says the source close to Tata. He contended that shareholders of Tata Power, Tata Sons (directors other than Mistry) and the trusts deserved to know what was going on, especially since it is Tata Sons that lends the respected Tata brand to group companies to use (in exchange for a royalty payment), which they leverage for operational benefits, including attractive terms for fund raising.

However, the source in Mistry’s camp says information on the potential deal was adequately shared with the Tata Sons board from time to time. This was done especially since Mistry didn’t want to run the risk of the Tata Sons board voting against it at a later stage, which could have jeopardised the transaction. Moreover, as chairman emeritus of Tata Power, Tata would have also received the board papers in which details of the discussion on the proposed acquisition would have been outlined, he says.

The Tata version points to Mistry’s actions over the last four years as being a systematic attempt to dismantle the conglomerate structure that Tata had painfully put in place. Mistry’s loyalists claim that all he was trying to do was set up a governance framework that would outlast Tata, himself and any subsequent Tata Group chairman, and secure the future of the institution. Mistry is still a director and chairman on the boards of various group companies, many of them listed, but not the chairman of Tata Sons any longer.

In a sensational twist at the time of going to press, the independent directors on the board of Indian Hotels Company Ltd, of which Mistry is chairman, expressed “full confidence in the chairman” and praised the steps taken by him in providing strategic direction and leadership to the company. This queers the pitch further for Tata and adds to the ambiguity on the future course of action, which may involve long-drawn litigation. The battle just got more intense.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)