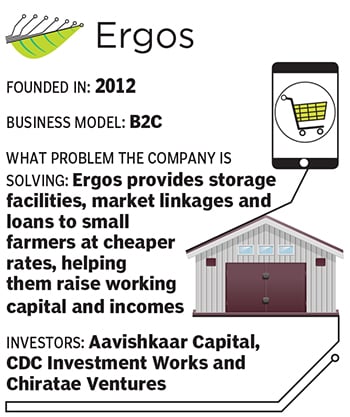

Ergos: Grain as an asset and currency

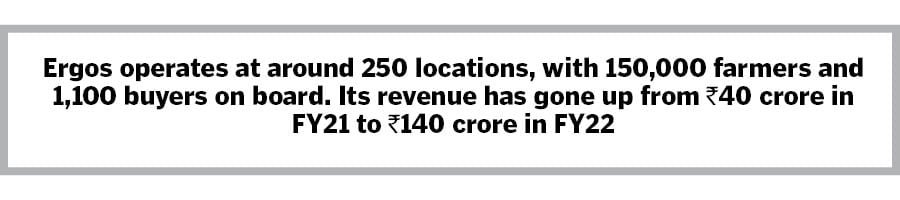

By creating grain banks, Ergos is converting farmers' harvest into a collateral which can be used to access finance—it operates at 250 locations with 150,000 farmers and 1,100 traders

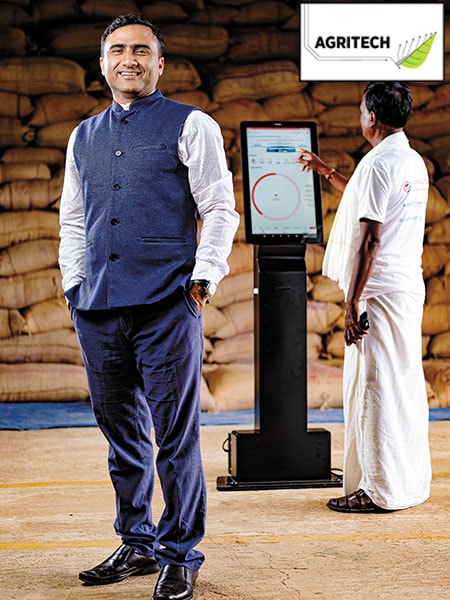

Kishor Jha, founder and CEO, Ergos.

Kishor Jha, founder and CEO, Ergos.

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Ten years ago, Kishor Jha and Praveen Kumar decided to put their banking and corporate experience to use in the farming sector. Both came from a farming family background and had seen the problems faced by farmers when it came to selling their grain and raising working capital. Most marginal farmers—which form about 80 percent of the community—rush to sell foodgrain immediately after harvest to repay the money they would have borrowed from a moneylender, typically at a high interest rate.

“When the grain is ready, more than 80 to 90 percent farmers end up selling everything within 30 to 40 days,” says Jha on a call from Bengaluru. Even if they are not in debt, there is no place where they can store their grain since most commercial warehouses are not at village locations, but are situated closer to consumption centres. Jha and Kumar wanted to turn that grain into collateral, an asset that small farmers could pledge with a bank and access finance at a lower rate, as well as sell over a period of time according to their cash flow needs.

So they leased a warehouse in Bihar and asked small farmers to deposit their grain with them. After checking the quality of the grain, just like a bank, they issued a khata book and made entries in the passbook. Their startup, Ergos, founded in 2012, made the warehouse a grain bank, and grain a farmer’s currency.

And while a buyer might not go around buying 10 to 20 bags each from several farmers, integrating the stock meant a buyer could even buy a 100,000 bags belonging to several farmers from an area. “That’s the model that actually unlocks the value of selling even one bag to a buyer,” says Jha, founder and CEO of Ergos.

The operation remained offline until 2015 when the bootstrapped startup got its first funding of Rs 4 crore from Aavishkaar Capital and they invested in technology. An app put the passbook online so that farmers were able to access their details on their phone and transact at a click. “We had a tech platform running in November 2016 and started educating farmers that once they had the app, they didn’t need to come to us and update the khata book,” says Jha.