Returns on rice: The making of India's biggest basmati exporter

Anil Mittal's family business KRBL is reaping the benefits of its decision to penetrate the domestic market with new brands and varieties of basmati, while maintaining a strong export business

Anil K Mittal, chairman and MD, KRBL, says business was ingrained in him at a young age

Anil K Mittal, chairman and MD, KRBL, says business was ingrained in him at a young ageWhat’s in a name? A rose by any other name would smell as sweet, William Shakespeare had insisted. However, Anil K Mittal, chairman and managing director of India’s top rice exporter KRBL—makers of the popular India Gate basmati rice among other brands—politely disagrees, at least as far as his company’s name is concerned. “I wish we had retained the full name, Khushi Ram & Behari Lal, instead of the abbreviation, as it speaks volumes about our legacy,” says Mittal. “After all, there’s a lot in the name.”

The legacy that Mittal refers to spans a century. The company, headquartered in Noida, has come a long way since it was founded in 1889 in Lyallpur (present day Faisalabad in Pakistan) by Behari Lal—Mittal’s great grandfather—and his brother Khushi Ram. Back then, it had interests primarily in cotton-spinning mills; it was also involved in banking and textiles. Rice mills, now its mainstay, comprised just a miniscule part of the overall business then.

Today, KRBL is the world’s largest rice miller and exporter with over 30 percent share of the domestic and 25 percent share of the branded basmati rice export market. It runs two plants—one in Dhuri, Punjab, and the other in Gautam Buddha Nagar in Uttar Pradesh—with a combined milling capacity of 195 MT per hour, according to Karvy Stock Broking.

Apart from the flagship India Gate basmati rice, KRBL’s other basmati brands include Doon Basmati, Nur Jahan and Bemisal. While the company has mainly positioned itself as a basmati provider, in the non-basmati category its brands include Aarati.

In addition, the company also produces value-added products such as bran oil and has an installed renewable energy capacity—comprising bio-mass, wind and solar—of about 134 MW.

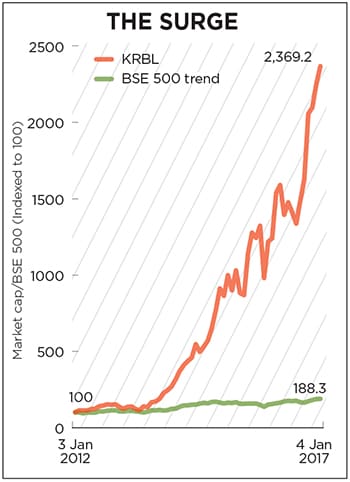

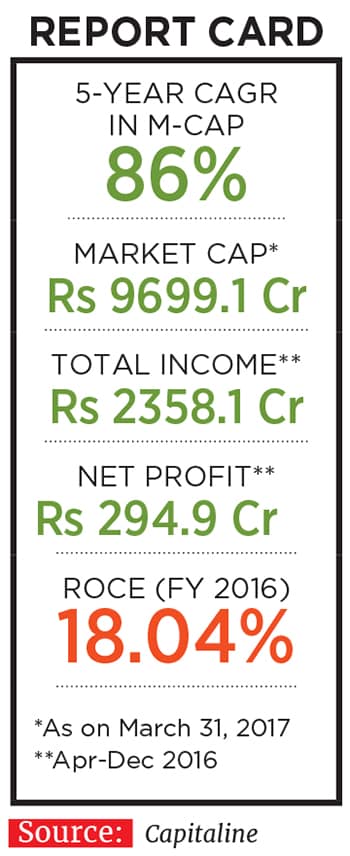

KRBL’s market capitalisation too has grown at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 86 percent over the last five years to touch Rs 9,699 crore on March 31, 2017. In the last one year alone, its shares have surged by 88 percent on BSE to touch Rs 430 on April 24, 2017.

“I believe the major inflection point for KRBL was after FY12. The management prepared a road map to increase the exposure to basmati rice and the domestic market,” says Deven R Choksey, managing director, KR Choksey Investment Managers. “The company developed a lot in terms of its distribution channel. This has helped them improve their penetration in the domestic market. Besides, they have increased their presence across different international markets, which has also reduced vulnerability in financial performance,” he adds.

For instance, Iran’s ban on rice imports between October 2014 and December 2015 only had limited impact on the financial growth of KRBL as it was largely offset by strong growth in other West Asian countries.

“Going ahead, the lifting of Iran’s ban on [rice] imports along with Indian youth showing a preference for basmati could aid topline growth for industry players,” says Choksey.

Business was ingrained in me at a very young age and I started working when I was all of 12, giving a helping hand to my father who had suffered a heart attack then,” the 65-year-old Mittal tells Forbes India.

After witnessing success in the cotton trade in Pakistan, Mittal’s family had migrated to India in 1947 during Partition. “It was a few years before my birth. My family came back from Pakistan in a chartered flight and landed at Safdarjung airport in Delhi. Life changed for everyone and business had to begin from scratch,” Mittal says, recalling the stories narrated to him by his father. While they had three other properties in India, the family chose to set up its headquarters at Naya Bazar, Delhi’s famous grocery market, and began as trade agents.

Scaling up, “from small to big”, is an easier transition than “falling from top to bottom”, says Mittal, pointing out that the hardships, then, are far more.

His family, he remembers, in the early 1950s had made a refugee claim worth Rs 3 crore to the government for lost property. Of that, assets worth Rs 1 crore were sanctioned and those rejected were claims for properties registered in the name of the company. “We were told we would get money only for properties registered in our name,” says Mittal. With the money they got—which was to the tune of Rs 3.5 lakh—KRBL started a business of running oil mills and rice mills.

Mittal officially joined the business in 1968. “Ours was a large family. I had many uncles who were a part of the business. I realised that if I had to make my mark I would have to do something innovative, even if that meant taking the same business forward.”

Mittal then briefly worked at his maternal uncle’s flour mill in Uttar Pradesh. “Those were the days when I was trying to do things on my own and it was an enriching experience that changed my life. Flour mills were like money-churning machines. I garnered enough experience to start off on my own.”

In the mid-1970s, Mittal bagged a tender to supply barley to the army. “That was the turning point in my life,” he says with a beaming smile, and “there wasn’t any looking back since”.

From barley, the transition to a full-fledged rice business, he says, was not too cumbersome. “KRBL was already in the rice business, but that was with the whole family. I decided to redefine the business and focus primarily on rice, changing the company’s name to Anil Trading Company. But soon after its success, I changed the name back to Khushi Ram & Behari Lal.” It became KRBL in the late 1990s.

The early years purely went into trading in rice. “We became suppliers to leading domestic exporters. And as fortune favours the brave, when India opened rice exports in 1978-79, life changed completely for us,” says Mittal, who kick-started the process to export the grain himself in the mid-1980s. “By then, we had already made a name for ourselves in the industry and also knew the key people. From supplying rice to big exporters, we decided to become exporters ourselves,” says Mittal.

“The remarkable growth that the company has witnessed has to do with the management’s involvement in every aspect of the business right from seed development to modern farming,” says Jagannadham Thunuguntla, head of fundamental research, Karvy Stock Broking.

Again, in the early 2000s, when KRBL introduced Pusa 1121 (the grains of which are slightly longer than Pusa basmati rice) to the market, it once again took the industry by surprise. This was a special basmati line developed by the Pusa Institute, Delhi, but the industry could not foresee its potential.

“I decided to cultivate and multiply this variety [Pusa 1121] in our contract farming programme on a commercial basis,” says Mittal.

KRBL’s own research and development team and scientists were involved in this project, and they were the first ones to bring Pusa 1121 into the market—export as well as domestic. “When Pusa 1121 was launched, it just swept the markets across the world. The entire industry was astounded with the sensational success of this variety,” recalls Mittal. According to company data, of the 12 million tonnes of basmati paddy currently being produced in India annually, Pusa 1121 accounts for about 6 million tonnes.

Another decision that Mittal claims to have worked in favour of the company is the takeover of Oswal Agro Furane, a sick unit in Punjab, from the High Court of Punjab & Haryana in 2003. Today, it is the biggest rice plant in the world with a capacity of 140 MT per hour and can process about 1 million tonnes of paddy per year which is about 7 percent of the paddy cultivated in Punjab.

The success of any business, Mittal knew, was not in the vision alone. A lot depends on execution too. “When I started doing business, I used to look up to large business houses. While it’s not fair to take names, it was my dream to grow into those kind of mighty and huge establishments one day,” says Mittal. “But over the years, I have also seen many reputed enterprises coming down drastically. The descents have been as quick as the ascents.”

“ I entered this industry as a young man... facing formidable competitors. The beginning was very modest and the journey intimidating.

Key departments such as human resources and marketing work in tandem to “choose the right people for the right positions, so that the right decisions are taken at the right time. And it is important that all the people are capable of thinking and acting in their individual capacity,” says Mittal. For any business to grow, an employee should be allowed to function like an entrepreneur in his sphere of activity, he adds.

The intrepid Mittal has travelled a fair distance in his entrepreneurial journey, but “there is still a big gap between my dream and my [position] today,” says Mittal. “I entered this industry as a young man, and I saw myself facing formidable competitors. The beginning was very modest and the journey intimidating. But you cannot give up.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X