R Ashwin and the spin evolution

From opening batsman to one of the world's best spin bowlers, Ravichandran Ashwin's journey has seen him embrace change at every step

“I believe making mistakes and making them on my own terms is very important,” said Ravichandran Ashwin at a press conference after the second day of the Mohali Test against South Africa in early November this year. He had come back to the side after missing a few games due to a side-strain injury, and just led a masterful spin-bowling offensive from India.

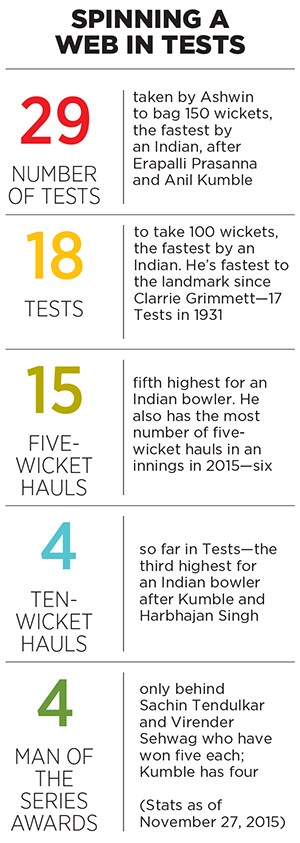

It, then, clearly wasn’t a day when he needed to dwell on his mistakes. With the final wicket of the first innings, the right arm off-break bowler had taken 150 Test wickets in just 29 Tests, the fastest Indian to reach that mark. The milestone came on the back of a stellar year, which included a 21-wicket haul in three Tests in Sri Lanka that ensured a rare series win for India and a Man-of-the-Series award for the 29-year-old from Chennai, who has made his debut in the 2015 Forbes India Celebrity 100 List this year at rank 31.

But his reference to the importance of making mistakes on his own terms wasn’t without cause. The recent resurgence had come after a dip in form in the previous year, following a flurry of mediocre performances in late 2013 and early 2014.

Eager to get out of the slump, Ashwin had experimented with a number of things. Briefly, during the Asia Cup, he had even changed his action and worn long sleeves a la West Indian Sunil Narine. “He was trying too many things and he confused variation with a different style of bowling,” says legendary off-break bowler Erapalli Prasanna, a member of India’s famed spin quartet.

Ashwin, however, believes that all the tinkering was aimed to improve his bowling. And the proof is in the numbers. He is now the highest wicket-taker in Tests in 2015 with 55 wickets in eight matches at an average of 17.81 (as of November 27, 2015—when India beat South Africa in Nagpur to win the third Test in the four-match series). “It’s very difficult to look back and say that this particular thing helped me with my subsequent success,” says Ashwin. “I think it’s the journey that changes things.” And it has been a remarkable one.

The tag of intelligent bowler is often used for Ashwin, and it stems from the fact that a student of spin bowling can tell when he is setting a batsman up, says Prasanna. “There’s no doubt about his capabilities. He shows the intelligent side of a bowler.” And that is the mark of a bowler who works to a plan.

“There’s a business-like approach to my game,” Ashwin tells Forbes India, “not in terms of money but in terms of growth.” Since his cricketing skills are his products, he says, they constantly need to evolve. There’s plenty to suggest the validity of this claim, not least of which is the fact that Ashwin began his career as a batsman. “My father was a huge cricket fanatic,” he says. Ashwin’s father, Ravichandran, was a medium-pace bowler at the club level in Chennai and would often bowl to him. “My dad was my initial playmate,” he says.

Subsequently, Ashwin began playing at the local Young Men’s Christian Association, and by the age of nine, at his school. He quickly went on to become one of the leading cricketers at the school level, playing first at Padma Seshadri Bala Bhavan and later at St Bede’s Anglo Indian Higher Secondary School in Chennai.

As he made his way up the ladder to first-class cricket, Ashwin changed his game dramatically. By 2004, he was a part of the India under-17 squad. “He used to open the batting for the India under-17 team,” says former India seamer Venkatesh Prasad, who had then just begun coaching the team. Prasad recalls that even then, Ashwin could bowl some off-spin. “I vaguely remember suggesting that he should work on his bowling,” he says.

Although the transformation from opening batsman to spin bowler was underway, Ashwin really began bowling spin by the age of 18. “It was a steep learning curve,” he admits.

It was also at this time that Ashwin found himself at a crossroads. “Most people don’t need to make a career choice at that age, but as a cricketer, you have to decide if this is what you want to do,” he says. Ashwin wasn’t quite sure.

Meanwhile, he began studying engineering at the Sri Sivasubramaniya Nadar College of Engineering in 2005 and cricket took a back seat for a short while. However, he continued playing higher division cricket.

Balancing the rigours of studying and playing cricket wasn’t easy. But Ashwin believes that made him mentally stronger. “I took that mental toughness onto the field,” he says.

After the early performances, Ashwin was called up to play the Ranji Trophy in 2006. And the following sequence of events led to him captaining the Tamil Nadu side in just over a year.

Ashwin had broken his wrist after a year of playing and had to sit out the matches. Not only did this make the team value his role in his absence, but also ensured that he give his engineering college semester exams. “I don’t think I would have passed had I not broken my wrist,” he says. Upon his return, he was appointed the vice captain in a squad that had been depleted because of an exodus to the newly created Indian Cricket League. To add to the long list of fortuitous occurrences, the captain fell ill just before the season began, and Ashwin was asked to step in; and because he was successful, he continued as captain. “I think besides the MJ Gopalan Trophy which was the first time I captained, I haven’t lost a game as captain of the Tamil Nadu side.”

While he had done well on the first-class stage, Ashwin’s breakthrough moment came with his inclusion in the Chennai Super Kings squad for the Indian Premier League (IPL). He spent much of his first season in the league on the sidelines, but in 2010, Ashwin managed to pick up 13 wickets in 12 games with an economy rate of 6.10.

Ashwin believes the claim that he is an IPL discovery is exaggerated. “I think what makes an international cricketer is first-class cricket. In 2010, when I really announced myself as an IPL player, I already had 100 first-class wickets.”

While that may be true, it was in the 2010 IPL season that the bowler wreaked havoc with the ‘carrom ball’, re-popularised by Sri Lankan Ajantha Mendis. Ashwin’s version of the delivery came from his time playing gully cricket in Chennai. “My dad didn’t like me playing tennis ball cricket,” says Ashwin. His father believed that it would be bad for his game. The carrom ball is bowled by a lot of gully cricketers, Ashwin explains. “By pressing the ball down and flicking it with your middle finger, you can give it a lot of revolutions,” he says.

After a lean phase in the Ranji Trophy, his father had suggested that he try the same thing with a cricket ball. “I dismissed the idea at first, as I do most criticism. Then I went to my room and thought about it,” he says. It took him about a year and a half to master the carrom ball, which he used extremely effectively in the IPL.

In June 2010, Ashwin made his one-day international debut in Harare against Sri Lanka; he scored 38 runs, but went wicketless. His Test debut which came over a year later on November 6 was more impressive. He picked up a total of nine wickets against the West Indies in Delhi.

“I would have thought that somebody with his kind of cricketing intellect would have been able to get just as many wickets abroad,” says former India captain Bishen Singh Bedi. “He is potentially outstanding.”

Ashwin can take you through a ball-by-ball account of the game that signalled his comeback from the slump. It was a World Cup warm-up match against Australia at Adelaide on February 8. Australia scored 371, but Ashwin bowled a tight spell of 6 overs for 29 runs, including one maiden over. “I had made a lot of changes on my wrist work and loading and it was very important that I use them,” he says. He went on to bowl three maiden overs in the opening World Cup match against Pakistan, and has been in the best form of his life ever since.

His transformation may also improve his effectiveness abroad, believes Prasanna. “He was used as a soft bowler overseas,” he says. “With the captain supporting him as an attack bowler, I’m quite confident he would be successful overseas too.” And he has started using his stock ball more often now.

While his journey is yielding substantial returns, Ashwin is still certain of his eventual plan to become a cricket entrepreneur. “I think he’s going to be involved with this game forever,” quips Ashwin’s wife Prithi, who has known him since they were in school together. He has the impatience of a man who knows his own potential and cannot wait to utilise it optimally. “If he has had a bad day, he’ll watch hundreds of videos and look for ways to improve,” says Prithi.

As a first step in his entrepreneurial journey, he has already opened a small cricket academy in Chennai. Ashwin has been running it for five years now, but the venture isn’t purely commercial. “I want to change the way cricket is played in Tamil Nadu. I want to leave a cricketing legacy of my own,” he says. When he’s not working on his game, he heads to the academy to work with the boys there. “It’s something I’m very passionate about, and to watch them play the brand of cricket that you want them to play is very pleasing,” he says.

Coaching plans, though, can wait. For now, he is back in the Indian side to continue his dream run with the ball. Cricket can be quite unpredictable, with varying conditions, pitches, fortunes. But so can Ravichandran Ashwin. Ask any batsman.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)