A different stardom: Celebrities in a world before now

What did being a celebrity mean in the era before 24-hour TV and the Internet?

In Nasreen Munni Kabir’s Conversations with Waheeda Rehman, the actor recalls an incident during the filming of CID and Pyaasa, two films that would make her a star. “In those days, you could hire a victoria [a horse carriage] and ride along Marine Drive, and I remember telling my mother: ‘Mummy, before my movies are released, let’s go for a ride in a victoria because I won’t be able to do it later.’” Her mother, Rehman remembers, was rather displeased at this idea, thinking, “all this has gone to your head”.

Whether or not Rehman actually went for a ride in a victoria after the release of her first two films is perhaps not as important as her observation: “I was recognised but not mobbed. When CID and Pyaasa celebrated their silver jubilees, I did become very popular. But stars did not have as much exposure as they have today. There were only a few film magazines like Filmfare and Screen, and people were largely unaware of how we actors looked off-screen. Now you open any newspaper and you see whole sections dedicated to movie stars. The stars today have lost their freedom that actors of my generation had.”

In a young India, being a celebrity was perhaps more about being respected, rather than being mobbed. Of course, famous faces on the silver screen were recognised: Eager fans hung around for autographs and sent in fan-mail by the cartload. What did not exist was the celebrity culture of today—with intrusive tabloids, 24-hour news and music channels, unending brand endorsements and live events (from poll campaigns to award ceremonies)—that has made celebrities omnipresent.

Sunil Sikand, son of actor Pran, remembers an era when celebrities “did not take themselves so seriously.” “My father could walk anywhere, and get all the respect; no one would behave badly with him. Dilip Kumar saab would go to Bandra Book Centre, and everyone would treat him with respect. Not even a single bodyguard. The celebrity today has cut himself off from people. He is surrounded by guards. They are like politicians.”

Sikand narrates an incident when his father stopped by his usual bar after work one day. But that evening, he did not have his car. He came out, and a local young chap ran to get him a cab. “When my father gave him a tip, the chap said, ‘Saab, hum aapke film ka pehla show dekhta hai. Isse kya hoga? Ticket nahin milega’. This would never happen now, unless it was a photo-op, with four cars following him.”

Conversations with people within and outside the film industry piece together the picture of a time when fame sat easy on the shoulders of industry giants. Bhawana Somaaya, film journalist and author, says, “The stars of the 1950s and ’60s had the freedom to live the lives they wanted. They did the shootings at a leisurely pace. They packed up by dusk and returned home like normal people. It was a regular job.”

On outdoor shoots, she says, actors took their families (at least one family member) along. Sometimes, if the shoot was a long one, even the kids came along. Which is what Sikand remembers. “My father was shooting for Kashmir Ki Kali. We occupied a houseboat, along with Sharmila Tagore’s family. The second houseboat was shared among other crew members. It was like a picnic! The local people knew there was a shooting going on, and would gather when the camera was in place. But they never bothered any of the family members.” There was never the need to control unruly crowds either. “If the people were really noisy, someone on the sets would ask for silence, and the people respected that.”

This is not to say that star-struck locals did not throng the sets. Rinki Roy Bhattacharya, writer and documentary filmmaker, and daughter of director Bimal Roy, laughs over a story she came across while researching for her book Bimal Roy’s Madhumati: Untold Stories from Behind the Scenes. “During the outdoor shoot of Madhumati in a little place called Bhowali, near Ghorakhal [in Uttarakhand], there was a young girl who heard that Dilip Kumar was in the vicinity. She got so excited that she ran out of her house to catch a glimpse of him, forgetting her dupatta behind, thus creating a minor scandal. I met another local resident who recalled how there would be traffic jams in the sleepy village during the shoot.” The girl, however, did manage to get a photograph of herself (and some other equally enamoured girls) clicked with her favourite star.

Ameen Sayani, the golden voice that had the country enthralled for decades with Binaca Geetmala, chuckles over an incident in 1957: “Once, a girl—at least I thought she was a girl—wrote to me, and got so friendly that she sent me a beautiful shawl. I was very embarrassed, and announced it on the radio, saying she should not send me such things because I am married and my wife would blow her top if she came to know about it. Soon, another letter of hers arrived, saying, ‘Beta Ameen, do you know how old I am? I am old enough to be your mother!’”

“But yes, there were other girls who wanted to marry me,” adds the 82-year-old Sayani, who continues to host a radio programme on Radio City. “One very famous star, Zarina Wahab, was once interviewed by one of the big magazines, and she mentioned that when she was in college, she was enamoured with Ameen Sayani and wanted to marry him. When the interviewer asked her why she had not married him, she said, ‘But, you see, in the days when I wanted to marry him, I had never met him’. She seems to have changed her mind after meeting me! Thank god I am not on television, else I would not have generated this much of interest.”

But what is it about film stars that make people go weak in the knees? It’s all about the screen, it seems. “Cinema, as a medium, creates stars,” says filmmaker Shyam Benegal. “The medium magnifies personalities, it demands that actors be of a certain stature, that they be larger than life.” Sikand echoes Benegal: “It is not like television. If the cinema screen is that big, then you need personalities that can fill it, and hold your attention.”

Rakesh ‘Rikku’ Nath, manager to more actors in the Hindi film industry than anyone else, believes that a star is someone you cannot take your eyes off while he or she is on screen. “Like Dharamji, you know. You will just keep looking at him. That is a star! Or his son, Sunny. Who else can rip a tube-well off the ground and swing it around? That is a star.”

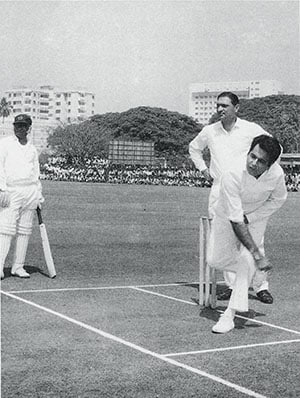

Image: The Times of India Group @ BCCL. All rights reserved

Dharmendra and Hema Malini at the July 1977 presentation of Sholay’s Gold Disc in Mumbai

This question, however, has remained a difficult one to answer. In a Stardust article titled ‘What makes a star?’, published in February 1973, the writer tries to unravel the factors that make for stardom. “Who is a star?” it reads. “Nobody, but nobody, has ever been able to pinpoint that special something that sets some actors and actresses apart from others and turns them into stars. Occasionally, the word ‘charisma’ pops up, but that is fast becoming the fashionable word to describe something that is difficult to explain.” The article goes on to look at the then favourites—Rajesh Khanna being a big one at the time—and discuss their attributes.

Yet another article in another film magazine from the 1970s describes how tourists in what was then Bombay would be taken to Rajesh Khanna’s house and how they would wait for him to appear at the window, which he eventually would, sending the crowd into a tizzy. Another magazine refers to a crowd of foreign tourists in Vrindavan, where Mumtaz was on an outdoor shoot, breaking into a song from one of her recent releases.

“Actors also played up the star act,” says journalist Sathya Saran. “They were always presentable, with their hair and make-up in place. They kept up that aura.” She adds that even when actors and filmmakers went through their dark days, they always showed their best side to the public. “They owed it to them.”

Akshay Manwani, author of Sahir Ludhianvi: The People’s Poet, says, “They [the stars] mingled, they had their huge fan following, but it was a lot more innocent and candid. I know this veteran film journalist called Ali Peter John and I was reading about his experience of attending Raj Kapoor’s Holi bash. That gave me the impression that back in the day, there weren’t really these filters between stars and even journalists. Now everything between the star and the journalist is all set up and calibrated before the message goes out.”

John’s account of Raj Kapoor’s Holi bash indeed paints a colourful picture: “I hated the festival, but I decided to go because first of all, it was my job that mattered and secondly because I always wanted to have a feel of what the most-talked-about Holi celebration in Bombay was all about. I reached the gates of RK Studios and before I could look up, I was welcomed with three buckets full of coloured water. I did not expect this, I was almost blinded when Randhir Kapoor, Rishi Kapoor and two other men carried me and flung me into a pool of coloured water. I stumbled and turned thrice in the pool, gasped for breath and called out for help, but no one was listening. I was finally pulled out by Rishi Kapoor who pushed two bottles of beer in my hands which I finished in 20 minutes flat… Raj Kapoor was sitting with his wife, Krishna, completely drunk before noon, all covered with colour of every kind, embracing people whoever they were, dancing with the well-known Kathak dancer Sitara Devi and generally having a good time. I went up to him to seek his blessings. He embraced me and ruffled my hair without caring to know who I was, and then asked some men to throw me into the pool again.”

Things, however, did not continue to be as carefree and candid. There seems to have been a shift in the concept of stardom from somewhere in the 1970s. “The stars of the mid-’70s are all still visible, they are all still active, they are all still making money, and they are also seen on the big screen,” says Somaaya. “If you move a decade behind to the ’60s, stars like Asha Parekh, Sadhana, Nanda, Helen are not as visible. Because, I think, they had kind of packed up when the technology started changing. Temperamentally they are different, and their grooming has been different. So, I would say the ’50’s and the ’60’s stars are more shielded, more private, and lead a life of their choice.”

The swinging ’70s were the age of Technicolor and Eastman Color, bigger films, bigger budgets, wider distribution networks, and brash new actors. What changed dramatically was how films were made. In the ’50s and ’60s, actors worked on one or two films at a time. The ’70s saw the rise of the ‘shift’, where actors worked on three or four films at the same time, moving from one set to another, and another, all in the course of the same day.

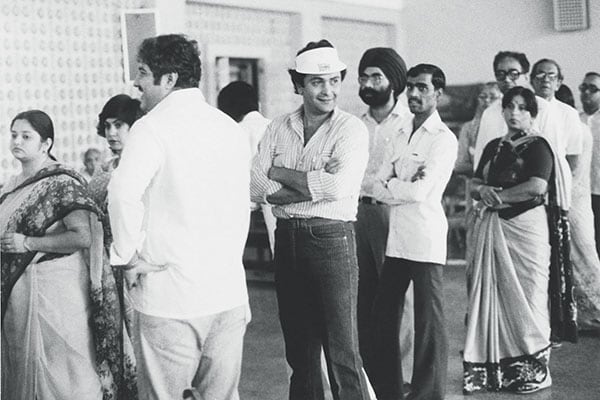

Image: The Times of India Group @ BCCL. All rights reserved

A nonchalant Rishi Kapoor stands in a queue to cast his vote at the Pali Hill (Bandra, Mumbai) booth during the 1984 Lok Sabha elections

An article titled ‘Two hours a day, five days in a year’ in the January 1980 issue of Filmfare rues this culture: “Most stars, big and small, have an absurd bagful of assignments, as many as fifty to hundred each… A star today is as sincere to his films as would be a novelist engaged in writing a dozen novels at the same time… For instance, the maker of a big multi-starrer told me the other day that he has already picturised the death scene of each major star in his film—if ever any one his stars decides to act ‘difficult’, the filmmaker has a ready death scene to terminate the star’s role.”

It continues: “When you watch Amitabh Bachchan, Dharmendra, Rajesh Khanna or Hema Malini on screen, do you realise that the sixty to eighty minutes of a star’s presence on the screen results from shooting spread across two to five years, with an indifferent star often staggering on to a set many hours behind schedule and then hurrying away after a couple of hours to report for another film on another set, many miles away, there, again, to be greeted by an anxiously waiting producer.”

Rikkuji provides the counter argument to this rather scathing attack. “I have seen Dharamji shoot simultaneously for one film in Calcutta, another in Khandala and a third in Bombay. Every morning, he would take a flight to Calcutta, finish his shoot by afternoon and return to Bombay for the second shoot, and the third at Khandala.”

The ’70s also saw the rise of star rivalries. Turning the (digital) pages of newspapers and magazines at Pune’s National Film Archive of India, there emerge stories of how Rajesh Khanna, insecure with Amitabh Bachchan’s rise, wanted to do films in which his character dies because he believed Dilip Kumar became most famous for his tragic roles. Another catty article, predictably in Stardust, discusses the rivalry between a rising Rishi Kapoor and a waning Rajesh Khanna.

“Earlier, film actors would get together for dinner, even amid their really busy schedules, and go to restaurants like Gayland or Gazebo,” says Rikkuji. “Gradually, that feeling of closeness went away.”

Adding an insider’s perspective is Hema Malini in a 1985 Filmfare article: “Men are so vain they won’t agree to play the father of a 10-year-old child. They are scared they will lose their star status. And if they play the father they also want to act as their own son. As if they want to say, ‘Look, I am really still young’.”

Another new brat in the film town was, actually, Stardust. Earlier, there were publications like Filmfare and Screen, both a comparatively sedate form of film journalism that carried harmless industry news and tidbits. Filmfare’s first issue, published in May 1952, for instance, had features like ‘Nutan Twinkles at home’, which carried photographs of a 16-year-old Nutan practising her singing alongside mother Shobhna Samarth, making chapatis at home, and lounging with comic books and her pet terriers. Even a decade later, in 1962, it carried columns like ‘My most embarrassing moment’, in which a very young and bashful Tanuja describes ‘My first kiss’.

“Journalism was much more sincere, in the sense people did not twist quotes out of context to suit the purpose of the story, something that I find now,” says Manwani. “Film stars are also more wary of that today; everything gets blown out of proportion on Facebook and Twitter.”

Stardust brought in gossip in the form of the column ‘Neeta’s Natter’, and a brand of film journalism that was hitherto unknown and revelled in making film stars uncomfortable. An example: The insider’s dope on Zeenat Aman’s divorce and her link-up with Pakistan cricket star Imran Khan in 1980.

The attitude of the public towards celebrities too began to witness a shift. “The first sign I got of the changing public reactions was when I was an assistant director to Manmohan Desai and we were shooting for Suhaag [1979] at Worli,” says Sikand. “It was a night sequence with Parveen Babi and Shashi Kapoor. And someone threw a small stone. It was mischief. But it was the first time that I realised that maybe times have changed. That didn’t happen before.”

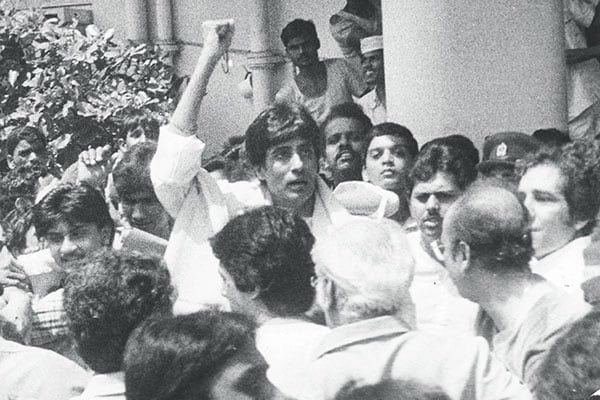

Image: The Times of India Group @ BCCL. All rights reserved

I am back: Amitabh Bachchan is thronged as he leaves Breach Candy hospital in September 1982 after recuperating (for over two months) from an injury on the sets of Coolie

Saran recalls a more disturbing incident in the late 1980s. “Tanuja was attending the opening of a beauty parlour in Calcutta along with her co-actor Victor Banerjee. The crowd went berserk, tore down the shamiana, and Victor had to literally rescue Tanuja and pack her into a car.”

Sikand wonders what has caused this tectonic shift in the public’s attitude. “Either people were more respectful or they were not so much in your face. I find that missing today… Maybe it is because of the increasing population and pressure on people. One reason may be because whoever’s important enough has cut himself off. So, when they go to a mall, the crowd is all controlled. And then, when someone does not have that control, the crowd goes into a frenzy.”

“The fact that everyone has a camera phone has made a lot of difference,” says Manwani. “I have seen instances when film stars did not want to be photographed at airports, but people were clicking away happily. I also read an interview of a film actor who said he doesn’t have a problem posing with anyone so long as they take his permission.”

But while satellite television, cellphones, social media, the internet (and its appendages) have widened the reach of celebrities than ever before, has this exposure eroded that magical element of stardom that celebrities of the pre-internet and pre-endorsement era thrived on?

“Earlier, there was an air of mystery that surrounded the stars; it made them larger than life, contributed to their magnetism,” says Benegal. “They were somewhat removed.”

Today, the likes of Twitter and Facebook have ensured that those days are gone, for good.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)