Virat Kohli: The Gladiator

At 25, Virat Kohli has already achieved more on the cricket field than most do in their entire careers. That attitude coupled with remarkable skill has made this man an unconventional role model and a marketer’s delight. Oh, and the swagger. That helps too

Virat Kohli is nothing like the universally loved, happy-go-lucky, pudgy-around-the-edges cricket superstars he grew up idolising. He is, perhaps, their antithesis. Arguably India’s best batsman today, he has a polarising effect on the cricket-crazy millions where even some of his admirers are not sure if they ‘love’ him. But Kohli doesn’t need to be liked as long as he delivers. He is oblivious to the expectations from a typical Indian cricketer’s personality —placid, conciliatory and pleasant. He is unapologetically aggressive and fiercely athletic. The swagger keeps the marketers and the media interested but what has earned him the admiration of the youth of this country is his skill, commitment, focus and attention to fitness. There is little doubt that he is the new, irreverent face of Indian cricket. It is a heavy responsibility, one that is still sinking in because this transition, over just the last year-and-a-half, has happened so quickly. “I am still only 25, so it is very hard to sit down and think of myself as a role model. Even now, if I have the option, I will grab some of my friends, walk into a mall and go eat at a store that I like. I am that kind of a guy,” Virat Kohli tells Forbes India. “I don’t like [having] drivers or servants. I drive myself.

I do stuff at home myself. It is hard for someone like me, who has done everything all by himself all his life, to suddenly start thinking that people actually want to follow me.”

The (Role) Model

For an outsider, ad film shoots in Mumbai can be fairly surreal. Hundred or so people buzz around the large studio: The bearded, tattooed, earring-wearing ‘creatives’ from the advertising agency argue with the suited executives from the client’s side while bereted directors orchestrate operations in between cups of green tea. Sitting patiently, quietly, in this maelstrom is the ‘talent’.

Kohli is taller than you would expect. He surveys the spread of chips, chocolates and soft drinks and reluctantly grabs some organic wheat crackers. “It’s all junk,” he sighs as the director calls him over to the set. Mahendra Singh Dhoni walks in silently, entourage first. Kohli greets him and they begin almost immediately. Both have the thousand-yard stare of professional athletes who have come to accept this necessary nuisance.

Kohli is interested in how he appears on camera and goes over to the director to review each shot. He has been filming for four hours, for an energy drink, after flying into Mumbai from Delhi where he had been shooting for two days. We sit in his trailer and he lies back on the bed. “Long day?” we ask.

“This is nothing,” he shrugs with tired shoulders.

“We shot for 14 hours straight with Anushka Sharma,” says his assistant. “Three days back-to-back.”

The last time he took a holiday was eight months ago, before the 2013 IPL, for four days in Dubai. This is Kohli’s life now. “I used to enjoy these shoots. Now I am professional about it. I come in and do what I am asked,” he says. At just 25, his success on the cricket field has earned him 13 ongoing endorsement deals, including one with Adidas reportedly at an unprecedented Rs 10 crore per year—this puts him in a league of his own. The company had paid this amount just so their rivals couldn’t have him.

Kohli has the posing down to an art. He lowers his head and glances at the camera side-on. Take after take, he walks back to his starting spot—much like a bowler—and executes his lines till the director is satisfied. He speaks with a cold gaze and steely expression because that is what all the brands want: A tough, intimidating image, not the smiling faces that Sachin Tendulkar and Virender Sehwag would put forth.

A young boy waits nervously with his father, a pen in one hand and a bat in the other. He has been on the set for the last two hours and, during a short break, when Kohli takes his seat next to his stylist and manager, the duo takes their chance.

“What’s your name?” Kohli asks the boy as he puts the bat across his lap to sign it. He is learning what it means to be a role model. “This is what I wanted to become. This is what I wanted my life to be like. This is what my dream was: That people will one day want to be like me,” he says. “Now when I see kids coming up to me for pictures or with hairstyles like mine or to tell me, ‘I want to play that shot like you,’ it’s very sweet.”

The boy walks away triumphantly with his signed bat. His day has been made. “I make sure I meet all the small kids who are aspiring to play cricket. I don’t want them to think of a cricketer as someone who becomes a star and then becomes arrogant,” he says. “...I make sure I make the kids happy because I want to keep them inspired.”

Already an international star, it is easy to forget how young Kohli still is. Till he reminds you. He loves playing football game FIFA on his Playstation with his friends. “I have got all the editions from 2008 to 2014,” he says. “I haven’t got the PS4 yet—I’m probably going to bring it back from South Africa.” And, of course, he is a fan of Spanish football club Real Madrid and their talisman player Cristiano Ronaldo. “I was shooting for Adidas and they presented me with a Real Madrid jersey signed by all the players,” he says. “They are planning on flying me to Brazil for the World Cup next year. I want to go and watch one of the El Clasicos in Spain too. It’s all planned, but I just want to take the time out to do it!”

The Fighter

Kohli’s admiration for Ronaldo is interesting, even logical: The two superstars from different sides of the world have much in common. They are divisive figures; both are admired and criticised for their perceived arrogance. Both lost their fathers early. Both burst onto the scene as talented teenagers carrying huge expectations, and transformed themselves into supreme physical specimens. They know how to have a good time but neither drinks nor smokes. Both are fitness and nutrition fanatics who developed thick skins to the negative press. Instead, they answer their critics through their performances.

Those who know Kohli point to a frighteningly driven athlete who is being groomed to lead Team India. A far cry from the stately, elegant players of the generation before him, he represents a new breed. He is a mentally strong, professional athlete first, talented cricketer second. Kohli’s ability to win in high-pressure situations as well as his focus on diet and physique has already anointed him a leader among the young players.

The fallout: He is in the spotlight and, inevitably, his aggression has become a talking point. However, Kohli has developed a thick skin to criticism. For him, his attitude is just an intrinsic part of his game. “Everyone has a different personality. I don’t think being quiet on the field works for me. I get into a zone where I become lazy and I don’t think too much about the sport,” Kohli says. “I want to channelise my aggression for my benefit and the team’s benefit but I don’t want to cut it down.”

It is an attribute that has given him much success and it is something that he intends to hold on to. “Obviously I wouldn’t want to cross the line as far as playing cricket is concerned. When you get older, you grow up, you become mature and you want to set an example for people watching you. You want to cut down on a few things but that competitiveness is what is making people believe that we can win,” says Kohli. “I want people to get inspired by that. It impacts the whole team. When you get into the face of the opposition, your teammates come along [with you]. In the Champions Trophy final, when India defended a small total, the team got the belief that we are together. We are here to win. We are here to compete. We are not just participating. I hate losing. I feel horrible.”

He is aware of the impact his behaviour may have on the impressionable generation. “I don’t want kids to get inspired by the line that has been crossed at times. I want them to get inspired by us taking Indian cricket forward and being in the face of the opposition,” he says. “People need to appreciate that we are good enough and we are talented enough; you can’t just come around and bully us. This is the new face of the team which people need to see.”

The Athlete

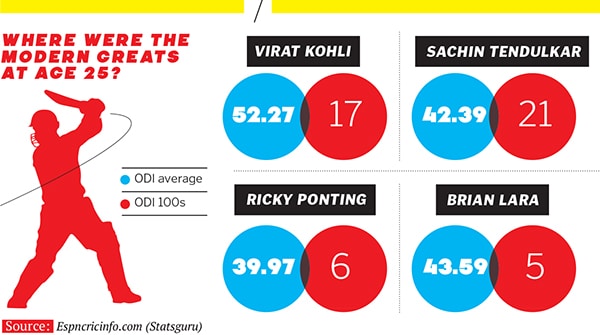

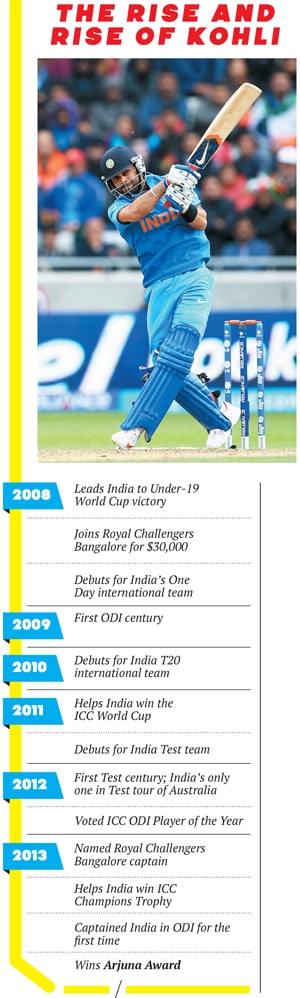

At 25, Kohli has already achieved what most cricketers would be proud of at the end of a 25-year career. He is arguably the best ODI player in the world. In 2011, he won the World Cup; in 2012, he was voted the ICC ODI Player of the Year; and, in 2013, he won the ICC Champions Trophy, became the top-ranked ODI batsman in the world and hit the fastest ODI hundred by an Indian. There is a reason why he is touted as most likely to break the records set by Tendulkar.

But what sets him apart is his ability to chase huge scores with staggering ease: He scores a 100 every six innings, averaging 65 when chasing. He has the highest conversion rate of 50 to 100s in the history of the game and is the joint fastest (appropriately with the legendary Viv Richards) to reach 5,000 runs.

His batting is the more visible aspect of his game that invites most of the plaudits. But, quietly, he has been a catalyst in another revolution that has taken place in the Indian team: In the fielding department. When India won the Champions Trophy in cold, swinging English conditions, they were, astonishingly, the best fielding side in the tournament, snapping into inner-circle stops and sliding near the boundary rope. For many older fans, seeing young athletes throw themselves around like the Australians or South Africans was unimaginable a decade ago.

“The fitness culture is there in the team right now. You see everyone hitting the gym and training in groups. You see the guys helping each other with fitness routines and asking the trainer to push them hard every week,” says Kohli.

Former India and Delhi player Vijay Dahiya is one of Kohli’s early coaches. “I never had to find him for fielding practice—he was always there. As a young kid trying to break into the India side, he said ‘If I’m not batting, how can I impress?’” says Dahiya.

What helped here was his fixation on fitness. Kohli started a fitness and diet regimen in 2012, after the IPL. “I don’t think I was fit enough to be an international sportsperson,” he says, “I wanted to be the best that I could be, the fittest possible, to improve my speed on the field.” He has used physical fitness to set himself apart. “In our country, fitness wasn’t the prime focus... No one would make that extra effort to actually tell you to train properly. It wasn’t in the set-up,” Kohli says. “That helped my cricket immensely. I could focus for longer periods; if I was physically fit, my mind could respond to what my body wanted to do.”

The fitter the athlete, the less injury-prone he is and the faster his recovery time. “I’ve been playing non-stop for 32 months now. Every format—even in the IPL—I haven’t missed a single game,” says Kohli.

He has combined physical training with a sensible diet plan. “Guys are taking care of the kind of food they eat. We have a trainer who keeps a check on the food that comes into the team changing room. Otherwise, on a regular basis, it is more of a personal choice,” says Kohli. “When you are tired you just eat whatever is in front of you—so you might as well get the healthy option. That sort of change has come about and it is helping the team’s cause. If you have 11 fit players, you will see it in the performance.”

Of course, he finds it harder to stick to the plan when he is back in Delhi and is faced with butter naan and butter chicken. “I am a Punjabi boy! We usually have a tendency to put on weight pretty quickly,” he says, laughing. His strategy is to not eat more than the calories he has burned. “That keeps me in check. I try to eat as light as I can for dinner. During game time, I have protein shakes with carbs. And I take my carbs from good sources. I don’t touch junk food unless it is in a place like Kochi where you are completely drained and it is a one-off,” says Kohli. “People also suggest you shouldn’t make your body totally alien to this kind of food. Once you have a craving, it has a very bad effect on you so I try to have those ‘cheat’ days in between, but I don’t go overboard. The very next day, I make sure I burn that off.”

The Talent

Dahiya remembers the first time he saw Kohli play. “In Delhi, at the Under-15 level, there are a lot of players. Take Sehwag, Gambhir, Virat, Shikhar and multiply that by 100. There are a lot of distractions growing up in Delhi,” he says. But what stood out about Kohli was his consistency and focus. “He was single-minded, mentally strong and his body is now responding,” Dahiya says.

Winning the Under-19 World Cup as captain in 2008 was a game changer. That was when Kohli came into the public eye. It was also the first time veteran cricket writer Ayaz Memon saw him.

“The first thing that came through was his aggression—at that age he seemed to be impetuous,” Memon says. “What struck me was that he was very demanding of his team-mates. It showed strength of personality.”

But his defining innings was his maiden Test hundred in Adelaide in 2012. Many will remember it for his pumped-up celebration but Memon believes that was the day Kohli realised that success in cricket is what makes him a role model, and not the tantrums. “You can show whatever attitude you want, if you don’t get the runs it doesn’t matter,” says Memon. “That 100 impressed upon him the need to make runs and that they are hard won.”

Kohli is at his most animated when talking cricket. It is quickly evident that he is a thinking player too—what may look spontaneous is, in fact, planned and executed with focus. Focus is a common refrain from everyone near him; they say it particularly comes to the fore when he is chasing down big scores. Consider that he has scored more than half of his runs in successful ODI run chases, where he averages 84 and made 11 hundreds. Perhaps his finest performance was the unbeaten 86-ball 133 against Sri Lanka at Hobart, Australia, in 2012. India chased down 320 in less than 40 overs and what stood out was Kohli destroying fearsome pacer Lasith Malinga. He innovated by going back in his crease and turning Malinga’s deadly yorkers into hittable deliveries. And it was all planned, he says.

“The second time I ever played against Sri Lanka and Malinga [in December 2009], I was in India and I scored my first century [in ODIs]. I was batting with Gautam Gambhir and we were chasing a total. I hit him for four 4s in the first over that I faced from him. I thought that this bowler is very difficult for a lot of people but somehow I find it convenient to play him,” he says. “In South Africa in 2010, in the Champions League against Mumbai Indians, I hit him for six boundaries. And then in Hobart, I thought of experimenting by taking my game to another level against him. On that day, it wasn’t much his fault either. He bowled really good yorkers but I was just middling it.”

His passion for chasing germinated early. Kohli remembers the first time he ran down a big score in competitive cricket. “We were playing an Under-17 match against Himachal Pradesh in 2005. They had scored around 385 runs. We had lost 4 wickets for 70 and were in trouble. I was batting and I scored 251 not out,” Kohli says. “We took the 1st innings lead. The last wicket, Ishant [Sharma], was batting for us. We had a 90-run partnership in which he scored 2 runs. That was the game that I single-handedly won for us; we scored 400 and I got 250. That was the first time I thought that whatever target is given to us, I think I am good enough to chase that down.”

Ask him about the science of chasing when the pressure is on, and he sits straight, his eyes light up.

“I like to think about the game a lot and chasing down a total allows me to do that. You can check the scoreboard, you can analyse how many runs you need to score in the next 5 overs, which bowlers you can target, how many singles you need to score, when you need to score a boundary, how many runs do you want to get in that over and the one after that,” Kohli says. “All those things are what I love calculating, taking control and being there talking to my partners saying, ‘What can we do?’” He rattles off scenarios. “It’s a large field, we can push the fielders, they’re back on the boundary, and we could irritate them with doubles and singles and by playing with soft hands. It’s lovely to have that challenge,” says Kohli, a fast talker who is unstoppable when discussing his craft.

Like many other greats, at his core, Kohli is a fan of the game. And, like every other Indian, he fondly remembers the days of India-Pakistan rivalry at Sharjah. “I remember [when we were living] in the first house that we had, I used to come back from school, finish my homework and do everything required before the game could start. When India used to bat second, I used to run to the shop next to my house, grab packs of chips and any other goodies that I wanted to eat. I would keep the bag next to me and watch India play,” Kohli says. “I miss Sharjah. There was nothing else like that vibe. India versus Pakistan at Sharjah: Those games were the best. The way Sachin used to win matches for us inspired me; I don’t think anything else inspired me so much.”

Kohli very evidently idolises Sachin Tendulkar. The only difference is that he now has access to the Master Blaster.

For him, Tendulkar is more of a confidant than an advisor. “He likes people who play with a lot of passion,” Kohli says, adding that Tendulkar has told him little things about his batting that he could improve on but, mostly, he gives Kohli confidence because he knows he thrives on it. “I just need to be mentally fresh for the game and I’ll be fine. He understands that beautifully,” says Kohli.

For him, Tendulkar’s final Test in Mumbai was the best atmosphere he has ever experienced. “I couldn’t speak to you standing three feet away, that’s how loud it was when he took off his cap to bowl,” he says.

He recounts the day he first met Tendulkar, before an Under-19 tour to New Zealand. “We had a three-day camp in Mumbai. Our coach Mr Lalchand Rajput called Sachin over to speak to us. We saw him walking towards us and we were so nervous,” says Kohli. “I don’t remember a word he told us because I was just staring at him. I couldn’t blink my eyes. I was starstruck!” Kohli’s jaw drops, mimicking his expression that day.

He clearly has a treasure trove of such stories but his assistant signals that our time is up. And Kohli must return to the studio for another three hours at least. Later, they were headed to Yuvraj Singh’s home for the night’s festivities.

“Anything else for today?” he asks his manager hopefully. “Yes, someone wants you for 30 minutes.”

His shoulders drop again: It’s a Saturday night and this 25-year-old will have to be at work for a little longer.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)