Power Shift: Can Mary Barra Fix General Motors?

Mary Barra made history by working her way into Detroit's car-guy club and becoming the first female CEO of General Motors. Now, can she fix the company?

Mary Barra, mother of two and the first female CEO of General Motors, sat silently while the parents of 10 dead children unloaded their grief and anger on her. Some read prepared statements; others spoke off the cuff. One father unbuttoned his dress shirt to reveal his daughter’s face on the T-shirt underneath. All were strangers but shared a tragic bond: Their loved ones died in a GM vehicle.

Renee Trautwein’s daughter, Sarah, 19, completed only one semester at her dream college before her 2005 Chevrolet Cobalt hit a tree. The air bag didn’t deploy. Doug Weigel’s daughter, Natasha, 18, died in Wisconsin after the 2005 Cobalt she was riding in crashed into a ditch. Randal Rademaker’s 15-year-old daughter, Amy, perished in the same crash. Susan Hayes’ son, Ryan Quigley, 23, died in upstate New York when his 2007 Cobalt landed upside down in a shallow stream.

The similarities were eerie: Young drivers lost control; air bags failed to deploy; keys were in the “accessory” position; all were driving 2005 to 2007 Chevrolet Cobalts.

“I’m truly sorry for your loss,” Barra, a dark-haired woman who bears more than a passing resemblance to actress Sally Field, said again and again, wiping her eye at one point during the nearly two-hour meeting at GM’s Washington DC office. The following day, April 1, Barra would appear before a congressional subcommittee investigating why GM waited years to recall Cobalts and other vehicles that could lose power because of a faulty ignition switch; she met with the families at the request of their attorney, Robert Hilliard.

“I put myself in their shoes and thought they deserved to be heard,” Barra told Forbes in late May, just days before the company was set to issue a report on what caused the ignition disaster—and what they planned to do to stop it from happening again. “It was very difficult for them, and I think they needed to know that General Motors cared and that we listened.”

Much as the families wanted to put a face on the statistics—at least 13 killed in 31 accidents—Barra, too, hoped to put a face on what she calls “the new General Motors”, a company that has spent much of the past five years shedding a reputation for poor quality and mismanagement, not to mention the taint of a $50 billion taxpayer-financed bankruptcy.

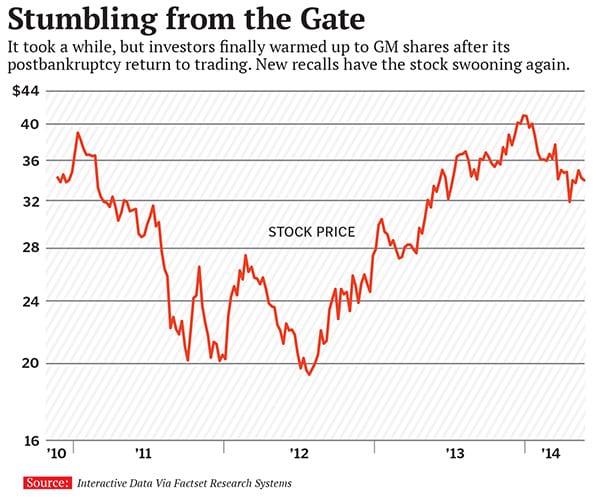

Being the face of GM is not easy right now. Instead of celebrating her historic achievement as the first female CEO in a traditionally male-dominated industry, a feat that landed her at No. 7 on Forbes’ 2014 list of the world’s most powerful women, Barra, 52, learnt of the ignition recall on January 31, just two weeks into her new job, and has been wrestling with it since. The original recall of 700,000 vehicles was announced on February 7, and twice expanded, to a total of 2.4 million vehicles. Since then, GM has stepped up its safety reviews and recalled some 13.6 million vehicles for everything from faulty tail lamps to potential seat belt malfunctions.

The crisis is an early, unexpected test of Barra’s leadership and has raised questions about whether the 33-year company veteran—or anyone—can really change the culture in an organisation as vast as General Motors, a company that has run through five CEOs in the last six years. Since the recall was announced, Barra has scrambled to stay ahead of the crisis, hiring an independent attorney, Anton Valukas, to lead an internal investigation and naming a new vice president of global vehicle safety, Jeff Boyer. Acknowledging that GM has both “civic and legal obligations” to victims, she tapped Kenneth Feinberg, who oversaw claims for victims of 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, to help GM assess its options for dealing with families’ compensation claims. And, in surprisingly quick fashion, she reached an agreement with federal regulators on May 16 to pay a record $35 million fine—the maximum allowed by law—and to submit monthly reports on its safety review processes for the next year. Results of the internal investigation and Feinberg’s recommendations are due soon. So far, GM’s board is happy with Barra. “The confidence has grown over a period of time, given the way that Mary has handled all the situations: Testifying before Congress, meeting with the media,” GM Chairman Tim Solso tells Forbes. “She’s done a superb job, and the board recognises that.”

Through it all, Barra has tried to keep some semblance of normalcy. She wears a Fitbit but doesn’t always get her 10,000 steps in. She admits she’s not athletically inclined (“It would be an affront to sports,” she says) and spends most of her free time sitting in the bleachers, watching her daughter play lacrosse, her son soccer. And yes, she felt horrible when she missed her son’s junior prom because she was out of town, though she has seen lots of pictures. “My kids told me the one job they are going to hold me accountable for is mom,” she says.

Mostly, though, she’s focussed on running America’s largest car company, which—despite the recall and all the negative headlines—has a lot going for it right now. GM is currently producing the best vehicles in its history, winning a string of awards from Consumer Reports, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety and others. GM’s four US brands—Chevrolet, Buick, GMC and Cadillac—now rank highest in customer satisfaction with dealers. GM sold 9.7 million vehicles globally last year, earning a net $3.8 billion on revenue of $155.4 billion. Earnings before taxes and interest were $8.6 billion, or 5.5 percent EBIT margin, up from 5.2 percent in 2012. New product launches like the 2015 Cadillac Escalade and the Chevy Colorado pickup should bolster Barra’s arsenal even more. And while there are problems—a slowed Chinese market, the stalled European economy—Barra is optimistic.

“I think from the product perspective we’re there, but we still have work to do to restore the company’s reputation,” Barra says. “Rebuilding takes time.”

But as the costs of the ignition switch debacle mount—recalls, suits and potential fines could wipe out most of 2014’s projected $5 billion profits—the risk is obvious. To survive, and thrive, Barra must get her “new” GM to finally—finally—emerge from the shadow of the old. And she needs to do it soon.

The most powerful woman in the history of the auto industry came to the business the way so many others of her generation did in the mid-1980s: through osmosis. Born Mary Makela, Barra grew up in Waterford Township, Michigan, a middle-class suburb north of Detroit, where local car dealers turned the arrival of new vehicles into small holidays, covering the windows to make a big production out of unveilings. Her father worked as a diemaker at GM’s former Pontiac division, wearing the same ubiquitous blue GM uniform as all the other Scout leaders, coaches and fathers in the neighbourhood. Her dad tooled around in a red Pontiac Firebird convertible, which she loved. “All of our dads worked at the Pontiac Motors division,” said Navistar CEO Troy Clarke, a former GM executive who lived in Barra’s neighbourhood and graduated from the same high school. “We basically grew up in an area where the people you were supposed to work with lived.”

As kids, both Barra and her brother Paul (now a doctor) excelled in math and science, and after she graduated high school in 1979 she landed a slot at the General Motors Institute (now Kettering University) in Flint, Michigan, a cooperative trade school founded in 1919 and run by GM from 1926 to 1982. She was sponsored by Pontiac, which meant the company paid for her education while giving her real-world experience. One of her first assignments as a co-op student was working at a Pontiac metalstamping facility, a harsh, noisy plant where huge industrial presses smashed fat sheets of steel into car parts. “It was the kind of environment that could frighten off a lot of people, including men,” says Clarke, who also worked there early in his career.

Far from frightened, Barra loved it and became hooked on manufacturing. After graduation in 1985, she went to work full-time at GM as a quality inspector in a Pontiac plant, helping churn out the midengine Fiero sports car. In 1988, GM paid for Barra to get her MBA at Stanford. Her roommate there, Catherine Malcolm-Brickman, recalls Barra’s proud parents and new husband, Tony—who also worked for GM—dropping her off at the dorm. One of her most vivid memories of Barra was the night an earthquake struck during the 1989 Giants-Oakland A’s championship. Huddled in the dark, terrified, with a bunch of friends, Barra chuckled. “Well, I guess there’s no World Series tonight,” she said, triggering a wave of laughter.

That duality—the cool, analytical engineer who could also keep her warmth and wits in a crisis—burnished a growing reputation as she rose in the company. In 1999, GM group vice president for labour relations Gary Cowger assigned her to improve communications with plant-level employees amid tense national labour negotiations. Under Barra, memos went from “talking about birth announcements, retirements and bowling scores”, as one former employee put it, to honest talk about which plants were making money and why they had to work the weekend to keep the company going. “Until then, people didn’t believe it.”

Four years later, she was running her own factory, GM’s Detroit-Hamtramck assembly plant. D-ham, as it’s called in GM-speak, opened in 1985, as a showcase for a new era of automation to combat Japanese competition. But the technology was so unreliable that GM spent as much time trying to get robots to behave as it did building cars. By the time Barra arrived, D-ham was reeling from reorganisations. For the first month Barra roamed the sprawling complex, talking to everyone. “When she walked the plant floor, she knew most people by name,” says her boss at the time, manufacturing manager Larry Zahner. It wasn’t all friendly. When she was preparing her budget, she decided to eliminate Christmas lights in the trees along the plant’s driveway. “I remember sitting across from her,” says Frank Moultrie, then the union’s shop chairman, “and saying, ‘Are you kidding me? We’re in that bad of shape that we can’t have the lights on for Christmas?’ ” They agreed to split the electric bill.

“It was never kumbaya,” adds Moultrie. “But it’s how you work on those differences that makes it work or not.” Within two years, D-ham saw double-digit improvements in quality and safety.

While Barra was fixing D-ham, elsewhere in the company GM readied the launch of the 2005 Chevrolet Cobalt, the car that would haunt it a decade later. When a small group of engineers began investigating reports that the Cobalt’s key could slip out of the “run” position when jostled, she never heard about it, Barra insists—D-ham made Cadillacs, Buicks and Pontiacs, not Cobalts.

Over the next few years, as Barra rose in the company—promoted to executive director of manufacturing engineering, developing factory processes and machinery—the switch problem was festering. In 2005, product engineers twice considered potential fixes to the switch but took no action, instead issuing a “service bulletin” in December 2005 advising dealers to tell customers who complain about unexpected shutoffs to remove heavy items from their key chains. In 2006, the ignition was quietly redesigned, without a corresponding change in the part number, a crucial error that escaped notice for years and likely delayed the issuance of a recall.

So should Barra have known about the switch? “You’re a really important person in this company,” Senator Barbara Boxer said after reading portions of Barra’s résumé at a congressional hearing in April. “Something is very strange that such a top employee would know nothing.”

Actually, Barra says it isn’t all that strange. With 219,000 employees today (326,000 a decade ago, when the switch problem surfaced), GM is a huge, complex organisation. There are 30,000 people in product development alone. As she noted during her testimony, it’s also not very good at communicating. “There were silos, and as information was known in one part of the business...,” she told the committee, “...it didn’t necessarily get communicated as effectively as it should have been to other parts.”

Beyond that, all automakers have a process for evaluating safety issues that deliberately doesn’t involve senior management because they don’t want undue cost influence. “I can’t intervene,” says Sergio Marchionne, CEO of GM rival Fiat Chrysler. “My technical people will decide.”

When the company imploded in 2009, saved only by President Obama’s justifiable fears of what closing the doors at GM might do to the fragile economy, Washington dumped CEO Rick Wagoner and picked Frederick “Fritz” Henderson to steer the company through bankruptcy.

Henderson named Barra to head human resources. She not only focussed on putting the right people in the right positions to get through the restructuring but also worked with Kenneth Feinberg, who was appointed by the Obama administration to set pay restrictions for GM’s top 25 executives while under government ownership. “She was a very effective negotiator,” says Feinberg. “She knew everything about the 25 people. But she was also very flexible. She didn’t come in with one rigid stance.”

After yet another short-term CEO (former AT&T chief Ed Whitacre) came and went, Barra’s predecessor Dan Akerson began the hard work of repairing the business. The two liked each other right away, and he merged product development and purchasing under her to streamline costs, where “she brought order to chaos”, he says, cutting a layer of management and giving chief engineers more responsibility.

Freed from billions in debt thanks to the bankruptcy, Akerson accelerated plans for GM to design more cars with fewer basic platforms, like Ford Motor and Volkswagen do. GM built a new finance arm and spent $1 billion rebuilding its IT department, which had been outsourced, giving the company a better handle on the data it needs to make smarter decisions. For the first time, for instance, GM can track how much money it is earning on every car sold in every market around the world.

In 2013, as GM’s board prepared for Akerson’s eventual departure, Barra became one of four candidates quietly considered for the top job. “I wanted to make sure she was absolutely the right choice,” he says. “The fact that Mary is a woman is great. But she earned this job on the merits of her performance and her potential.”

The leadership change came unexpectedly on December 10, 2013 after Akerson’s wife, Karin, was diagnosed with cancer and he decided to step down to care for her. He made her appointment as new CEO official outside a meeting room at Washington’s Mandarin Oriental hotel, where GM’s board was convened.

Given what was about to happen with the ignition recall, was she thrown under the bus? “Of course not,” says Akerson. “Mary has said it: The moment she became aware of the problem, as I would expect, she confronted it. She didn’t know about it. I bet my life on it.”

In the five years since GM exited bankruptcy, the company has gone a long way towards righting itself, which gives Barra room to manoeuvre. Its retail market share (excluding sales to fleet customers) has improved, while average transaction prices are up $2,000 compared with a year ago. On Wall Street, GM’s credit rating improved to investment grade, lowering its cost of borrowing. Chevrolet, the carmaker’s largest brand, sold a record 5 million vehicles last year, while GM also set a sales record in China, the world’s largest market. Since 2009, GM has invested $10 billion back into the US economy.

While 2014 will see only modest growth, Barra is sticking with Akerson’s mid-decade targets to achieve a 10 percent operating margin in North America, boost annual sales in China from 3.2 million to 5 million vehicles and restore profits to mid-single digits in South America and China, despite currency headwinds and economic turmoil, along with GM’s own inefficiencies. To get it done, she’s begun flying in her global leadership team for monthly meetings—not only to hash out important strategic decisions, but to also make sure they get to know one another better.

GM continues to perform well in the US and China, its two largest markets. Her plan is to use profits from those markets to restructure and make the investments necessary to grow profitably in other parts of the world. That task falls to President Dan Ammann, who is crisscrossing the globe, trying to find ways to share more products and expertise. At the same time, GM’s executive vice president for international operations, Stefan Jacoby, is tailoring GM’s product portfolio by country to meet consumer demand, rather than trying to compete on the fringes with irrelevant products.

In Europe, where GM’s fresh start in the US coincided with an economic collapse, the company is in the midst of restructuring, including a plant closing in Germany under new president Karl-Thomas Neumann, a former Volkswagen executive. GM toyed with selling its Opel division to concentrate on expanding Chevrolet in Europe, then thought better of it, and is now beefing up Opel’s lineup again. After $18 billion in losses since 1999, GM is now trying to break even in Europe by mid-decade.

Barra will also need to negotiate a new national contract with the United Auto Workers in the US, which will be looking to restore some of the benefits it lost when GM was in bad shape. Fortunately, the recall headlines haven’t hurt sales at home. In April, GM outperformed expectations, with sales up 7 percent from a year ago. Analysts like JP Morgan’s Ryan Brinkman think that the current spate of recalls might actually help sales of new GM models by driving more customers to dealerships to get their old cars fixed.

One thing Barra knows for sure: Painful as the recall has been, the crisis is an opportunity to finally break through the vestiges of the “old GM”. “I really feel—obviously we want to do the right thing and serve the customer well through this—but it’s also an opportunity to accelerate cultural change.”

A week after her grilling on Capitol Hill, Barra spoke to a much friendlier audience of several hundred engineers at a Town Hall-style meeting in the cafeteria at the GM Technical Center in suburban Detroit. The April 10 meeting was beamed across the world to all employees. “At this point, you’re probably town-halled out and probably just want to get back to work,” she joked. Her message would be familiar to anyone on the assembly line at D-ham a decade ago. “If we think there’s some information that another group would benefit from, pick up the phone,” she said. “Walk to the desk, send an e-mail.”

In the next week or so, GM will release details of the Valukas investigation, which Barra promises will provide a transparent summary of what went wrong. She’ll also outline further actions, which could include a shake-up of GM’s legal department.

Already GM has assigned one of the company’s top lawyers to advise global safety chief Jeff Boyer on legal matters. GM also expects a recommendation from Feinberg about whether there should be compensation for accident victims’ families and how much they should be paid. Then Barra will probably return to Washington to share an update on the investigation with lawmakers.

But that won’t nearly be the end of the controversy. GM is still facing an investigation by the US Justice Department and could face a fine similar to the $1.2 billion settlement Toyota paid recently for its history of tardy recalls. The company also faces five separate investigations and scores of lawsuits from customers who claim their cars lost value after the recalls were announced. The bankruptcy judge will decide if those claims have any merit. And through all of it, she’ll need to force change at the company and steer it to long-standing profitability and growth.

It won’t be easy, but Barra seems up to it. After GM set off a furore among parts suppliers in 2013 for changing terms and conditions without their input, senior executives fretted over how to resolve the controversy. “Mary’s feedback was, ‘If we made a mistake, let’s say we made a mistake and move on,’ ” said Grace Lieblein, GM’s vice president for global purchasing and supply chain. So that’s exactly what the company did. The reaction, says Lieblein, was stunning. “Suppliers came up to me and said, ‘This is the culture change you’ve been talking about.’ It’s about doing the right thing. In the old GM, I don’t think we ever would have done that.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)