Gujarat Pipavav: Profit in Sight For This Port

Pipavav port is seeing a turnaround葉hanks to some smart decisions and some serendipity

Name: Prakash Tulsiani

Designation: Managing Director

Age: 48

Favourite Sport: Golf, Billiards

Next Challenge: Pipavav finally in the black. Now needs to build competencies to take on Adani Port, arguably its biggest competitor

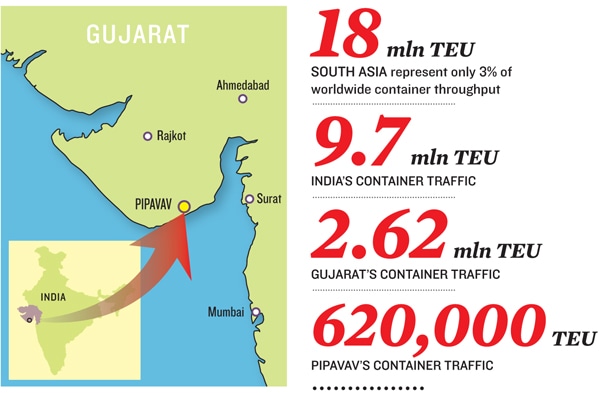

The port of Pipavav should have made money hand over fist ever since it started operations in 1998. After all, located deep in the Saurashtra region in south Gujarat, it is a gateway port that caters to landlocked regions like Delhi, the National Capital Region, Punjab and also the rich states of Maharashtra, Gujarat and Rajasthan. It handles more reefer trains (refrigerated trains that carry fish, meat, etc) than any other port in Gujarat. This is due to its proximity to major refrigeration centres of Viraval and Porbandar. Yet, it made losses for more than a decade.

All that changed in 2011, the first year the port made profits. In the 12 months ended December 30, 2011 (it follows the calendar year), it earned a profit of Rs 57.10 crore on revenues of Rs 366.19 crore—a significant jump from the Rs 54.72 crore loss it suffered in 2010. Today, Pipavav is one of the fastest growing ports not only in India but also worldwide.

One of the reasons for this turnaround is that Pipavav is gaining from the capacity crunch at Nhava Sheva port in Navi Mumbai, run by Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust (JNPT). The concession for building the fourth terminal at Nhava Sheva is mired in dispute. As a result, it cannot handle more shipping traffic (it is already operating at over 100 percent capacity). Ports in Gujarat are the primary beneficiaries—especially Pipavav, which is just 10 hours (one-way, about 152 nautical miles) steaming time from Nhava Sheva.

Now, 6 million TEUs (twenty foot equivalent units) per annum come into the north and north-west market which includes Nhava Sheva, Mundra and Pipavav. Assuming the market grows at 9-10 percent—a modest estimate considering that the growth in the container business has been double the growth in GDP—the three ports would handle an additional 600,000 TEUs per annum. With Nhava Sheva running at over capacity, “You divide the growth between Mundra and Pipavav in whichever way you like. Even if we get one-third, we’re looking at adding 200,000 TEU,” says a confident Prakash Tulsiani, MD of Gujarat Pipavav Port Ltd.

More than coincidence, it is Tulsiani’s effort, along with CFO Hariharan Iyer and COO Ravi Gaitonde that has turned around the port. These are the three men AP Moller-Maersk (APMM), the Danish shipping conglomerate, charged with the task of turning around Pipavav when it bought out Nikhil Gandhi, the founder, in 2005.

Nikhil Gandhi was the original brain behind Pipavav Port. In 1992, his company SKIL Infrastructure (then known as Seaking Engineers) formed a joint venture with the Gujarat Maritime Board (GMB) to form Gujarat Pipavav Port Ltd (GPPL). In June 1998 GMB sold back its initial stake to SKIL and in September, a concession agreement was signed in accordance with a Build, Own, Operate, Transfer (BOOT) policy. In June 2001, Maersk India, a subsidiary of APMM, bought a 13.5 percent stake in Pipavav. At around the same time, APMM formed APM Terminal Holdings to manage its port and termninal operations worldwide.

Four years later, the port was yet to start operations in full swing. So, in 2005, APM Terminals Mauritius (to which APM Terminal Holdings transferred the initial stake) along with IDFC Private Equity bought out Nikhil Gandhi and other strategic investors to gain majority control and signed a new concession with GMB in 2006 for a tenure up to 2028.

Profits would still take some time to materialise. The then Managing Director Philip Littlejohn’s priority was to get the project up and ready. But it took about 22 months to get the government approval to take effective control, and nearly 15 months to get approval for expansion of the port through dredging to increase the depth so it could handle larger ships—the delay meant cost overruns.

Sometime in 2008, APMM finally understood that in the Indian market, you need local managers to create a market for itself. That’s when it brought in Gaitonde and later Tulsiani and Iyer. These three are the trusted lieutenants of Maersk, having worked and risen up the ranks of the company in the last two decades.

Name: Ravi Gaitonde

Designation: Chief Operating Officer

Age: 53

Next Challenge: Has the onerous task of scaling up operations while maintaining the efficiency and nimbleness of the port

Tulsiani, who is from Mumbai, is a chartered accountant who had a great run in Indonesia with Maersk. He then headed a project that built out Maersk’s terminal at JNPT well before time. He is clearly a guy who knows how to get things done and can network effortlessly with government officials as well as customers.

Gaitonde is also from Mumbai. He led the teams that built out all three Maersk freight stations in India. Gaitonde also managed Maersk operations in Tanzania, whose sea is known for pirate attacks.

The three quickly pinpointed ways to boost up productivity at the port. One was to invest in post-Panamax cranes.

The port wasn’t able to turn around ships fast enough because of the Panamax cranes that it was using to load and unload ships. These cranes are 13 containers wide, sufficient for smaller ships that can pass through the Panama Canal in South America. But the bigger, wider ships are more efficiently loaded/unloaded with post-Panamax cranes that are about 18 containers wide. So, large ships—which bring in more traffic at a time, and are more profitable to handle—would create a bottleneck and because of the delay, give out adverse word-of-mouth feedback to future customers.

“At least in the first year, I didn’t make too many changes in personnel, in the operations, to get the productivity up,” says Gaitonde. Instead, what he did was to get in new methods of doing things—like better planning and empowering the staff. “Without me being top-down, it was more of motivating them to make it happen,” he says. And happen it did. The productivity, which was 15 ‘crane moves’ a few years back, slowly rose to 17, then 22 and is now above 30 moves per hour, one of the best in the country.

The second thing the trio did was consolidate vendors. Pipavav is surrounded by small villages whose traders and small businessmen have prospered by catering to the growing needs of the port. But managing the sheer number of vendors supplying truck trailers and bulk dumpers took up the entire time of the operations team. So, at the end of 2009, all vendors barring one were cut out overnight and that one vendor was made responsible for fulfilling the requirements of the port. This was more efficient and cost less because of economies of scale to one business.

Things have now speeded up at Pipavav. It has an existing container yard capacity of 850,000 TEU which it plans to shore up to 1.5 million TEU by end-2012. It has also brought in new Rubber-Tyred Gantry Cranes which are faster and are used to move containers within the yard.

In the past two years it has bought new software from a US-based company which designates a particular position to the container in the yard even before the ship arrives. The earlier practice was to do it on Excel spreadsheets, where you’d be looking at containers on the screen but would not actually find it in its designated place! “As soon as the container comes in, the surveyor on the ground updates it from his handheld device. Anytime if I have a container number, I know where it is”, says Captain T Jeyaraj, general manager, container operations at the port.

A port has three pillars: Container, bulk and liquid terminals. In that respect, Adani port stands tall. It operates one of the biggest bulk terminals in the country. It has well-established container and liquid cargo handling and storage. It has primarily benefited from having the first mover advantage even though Pipavav was the first private port in the country. While Adani port started operations in 2005, Pipavav took off around 2006-09 (after APMT took over). It had to build the container berth as well as the jetty from scratch, completely discarding the earlier one.

Among the three pillars, the one which gives fat margins is the liquid terminal business. Pipavav has a liquid cargo berth with a service deck of 65 metres. It first strengthened its position in container and bulk and then went ahead and signed deals with Aegis, Gulf Petro and IMC for the liquid terminal for oil and other commodities. “We went about it in a different way. We’re port operators, we’ll do everything up to the jetty and the company [client] would pump whatever commodity they bring into the tank farms prepared by them. We just lease out the land,” says Tulsiani. It’s an interesting proposition, whereby no investment is required by Pipavav and the entire burden is borne by the companies who will invest Rs 100-200 crore each for tank farms, pipes, etc.

“I suspect by the end of 2012 the third pillar should start showing up and by 2014, it should be completely up and running,” says Tulsiani.

Pipavav has also leveraged its parent company’s resources. APMM’s shipping line, Maersk Line, by far the biggest in the world, has an exclusive contract with Pipavav whereby if it calls at Gujarat it shall call only at Pipavav until March 31, 2012 (when the contract would’ve come up for renewal; there is no clarity yet on where the deal is headed). Considering the fact that Maersk Line currently provides 50 percent of the container volume and 30 percent of the revenue to Pipavav and has also built a hub there, it seems highly unlikely that it would shift base to another port. Also, at a time when the port has just about staggered on to its feet, it would need more stability before it can be left on its own by its parent. Having said that, the port has managed to attract other shipping lines, partly offsetting its dependence on Maersk.

But for many, while Pipavav may have turned in a profit, is it in safe harbour from a financial perspective? The investors have put in a lot of money and the return on employed capital has increased three times to 4.89 percent, but is still well below the cost of capital for the company. “When we took over in 2006, the infrastructure was not what the shipping lines required. We know what infrastructure should be there, Draught, jetties, yard, connectivity, roads. Everything. So, we had to invest in all that,” says Tulsiani.

In September 2010, GPPL came out with an IPO raising Rs 500 crore. It used majority of this money to pare down the debt, which currently stands at Rs 675 crore at an interest rate of 12 percent. Before the IPO, APM Terminals held 57.85 percent in the company which was then diluted to 43.01 percent after the IPO. Major fund houses like IDFC Private Equity, Credit Suisse and others together hold about 36.1 percent in the company.

Another issue about which there is some concern on the Street is that the entire shareholding is pledged. “The shares have been pledged for the purpose of project financing. When the financial restructuring happened, the lenders to the port, as additional security over and above the cash flows, wanted to have the shares pledged to them. There has not been money raised for any other purpose. There is no risk in the deal,” says an emphatic SG Shyam Sundar, partner at IDFC Private Equity and director on the board of GPPL.

The market at the moment is at a pause; the company’s stock price has been flat for the last one year. Time for Tulsiani and company to dredge up some more profits.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)