And When the Story Turned…

Twist in the tale can often be just a gimmick to have the reader hooked. In many books, surprise endings are central to the story's purpose

One barrier to discussing a ‘Twist-in-the-Tale’ narrative is that you can’t properly describe its effect without spoiling it for the reader. I anticipate that difficulty arising in this column, so let me first indulge myself by mentioning one of my favourite such stories, which you won’t easily find in print nowadays.

Stanley Ellin’s ‘The Question My Son Asked’, published in the mid-1960s, is narrated by a state executioner, a man who initially seems defensive about his profession but is really quite proud of himself. Unimpressed by anti-capital punishment arguments, he believes that anyone who commits a heinous crime no longer qualifies as human and must be destroyed the way a rabid animal would be. And of course, someone has to do the dirty work—to pull the switch for the electric chair. But the executioner now finds that his own son doesn’t want to continue in the family line. They talk about ethics, the son asks a provocative question, and the narrator, after hedging for a while, admits that it isn’t just a matter of social consciousness—he enjoys the power that comes with holding someone’s life in his hands and watching the effect of the electric current on a condemned man’s body.

What is impressive here is how the story initially seems to be about one thing and then becomes something else; how the tone goes from sombre, almost melancholy, to dark and macabre, and does this without undermining the more philosophical elements of the narrative.

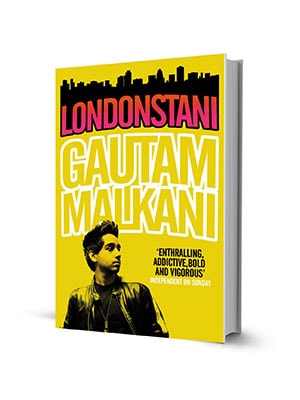

The tweak in the tale is a tricky thing to do well—it can often be a gimmick, aimed only at giving the reader a quick shiver. But there have been many books and stories where surprise endings (or mid-narrative surprises) are central to the story’s purpose. Serious literary fiction has sometimes hinged on major revelations: In William Styron’s Sophie’s Choice, the young narrator Nathan learns relatively late in the story about the terrible choice offered to Sophie, a Holocaust survivor, when she was in the concentration camp, and our attitudes to the characters are affected by this disclosure. And Gautam Malkani’s Londonstani, about the lives of a group of second-generation Asian “rudeboys” in London, ends with a surprise that overturns all our assumptions about the narrator’s identity.

But the best sources of good twists are anthologies in genres such as noir and science-fiction. The many gems in the collection The Best American Noir of the Century (edited by James Ellroy) include Harlan Ellison’s riveting, novella-length ‘Mefisto in Onyx’, about a man blessed (or cursed) with the ability to “jaunt” into the minds of other people. To his dismay, an old friend asks him to scan the mental “landscape” of a convicted serial killer, whom she believes to be innocent, and the story climaxes with a fascinating game of one-upmanship and one surprise following on the heels of another. I also recommend The Other Side of the Sky, an Arthur C Clarke collection that includes the celebrated ‘The Nine Billion Names of God’ (one of the subtlest end-of-the-world stories ever written) and ‘The Star’ (about the end of another world, not ours, with a shiver-inducing final sentence). For a wider range of sci-fi authors, try the Brian Aldiss-edited A Science Fiction Omnibus, which includes Bertram Chandler’s ‘The Cage’, a sobering tale that provides a sharp, cynical answer to the question “How do you know a species is capable of rational thought?”, and Ted Chiang’s beautiful ‘Story of Your Life’, about a woman who experiences the past, present and future simultaneously.

Roald Dahl is one of the masters of the story-ending frisson, and The Collected Short Stories of Roald Dahl is an excellent primer to his work. My favourites here include ‘Pig’ (young boy raised by his great-aunt to be strictly vegetarian must go out into the big bad world after her death), ‘The Great Automatic Grammatizator’ (a chilling cautionary tale about mass-production in literature, which seems even more relevant today) and ‘The Wish’, a tense story about a little boy playing a game on a colourful carpet in his house: He has to cross to the other side by avoiding the reds (which represent fiery coals) and the blacks (which are poisonous serpents). Dahl’s achievement here is that by the end, the carpet’s dangers are as real to the reader as they are to the boy.

Ira Levin was not as prolific as Dahl, but he was described as “the Swiss watchmaker of suspense novels” by none less than Stephen King. It’s a fine analogy, for Levin’s novels are masterpieces of construction. Since they are thrillers that can be read in a couple of hours, highbrow critics don’t think of them as “serious literature”; but it’s only when you try putting yourself in the author’s position that you realise the rigour and ingenuity involved. Most of his books accumulate details and surround a major surprise with a few minor ones.

Consider the structure of Levin’s brilliant A Kiss Before Dying. The first section of the book is about the plotting of a murder, and throughout we are privy to the ticking of the killer’s mind, his paranoid inner state. Yet here’s the rub: We never learn his name or anything that would allow us to definitely identify him. The implications of this emerge in the next segment of the narrative, where the focus shifts to another character who starts a private investigation into the murder. She encounters a few suspects, but the reader is now flummoxed: It is possible that the killer is one of the men she meets, but we have no way of knowing who it is. So ingenious is the change in perspective that a character who we knew intimately in the first section of the book is now a stranger to us. This is the set-up for the novel’s major disclosure, which occurs mid-narrative.

I’ll finish by mentioning an iconic murder mystery and a book ‘about’ that mystery. Though often downgraded today as a writer whose work centered too much on neatly packaged solutions, Agatha Christie was an expert plotter. In The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, her best-known novel, the revelation of the murderer was a shock to the system for first-time readers. But a tribute to that book’s long-term influence is that, decades later, a psychoanalyst was inspired to write a book-length study claiming that the real murderer was not the person named by Christie. In Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?, Pierre Bayard revisits the text of Christie’s book and discovers hidden currents that suggest an alternate solution. In the process, he deconstructs many aspects of the suspense genre itself, implying that the reader, not the author, is the final arbiter of a novel’s “meaning”. That may be the biggest twist of all.

The author is a Delhi-based writer and journalist

(This story appears in the July-Aug 2014 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)