India's richest give less than 1% of their wealth to philanthropy, but there is a ray of hope

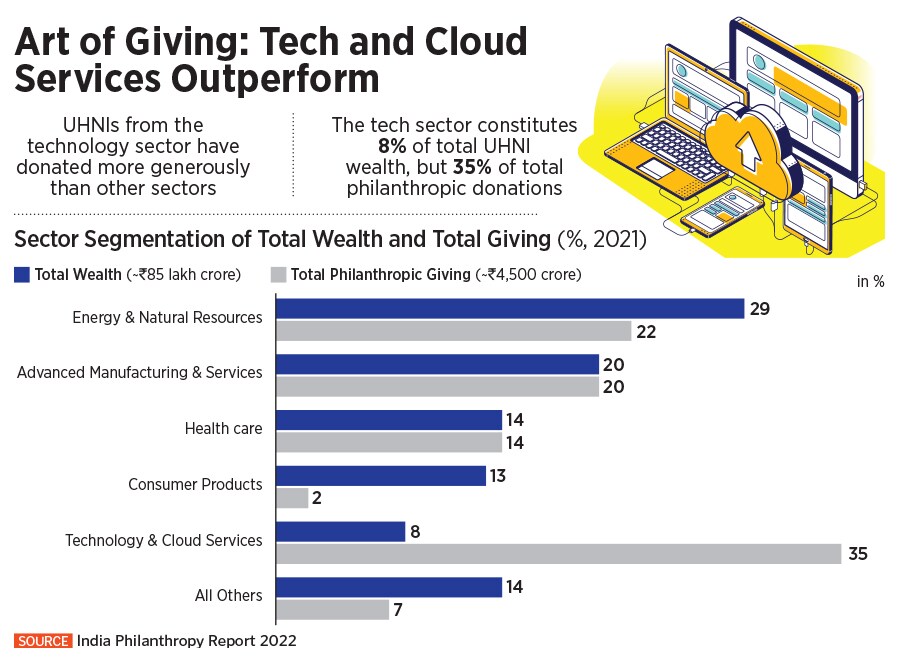

Younger philanthropists, with tech entrepreneurs in the lead, are making thoughtful social investments, says the India Philanthropy Report 2022. While the country's super-rich need to push the envelope of giving, we also need to build an ecosystem that incentivises philanthropy

Clockwise: Abhiraj Singh Bahl of Urban Company (Image: Pradeep Gaur/Mint via Getty Images), Nithin and Nikhil Kamath of Zerodha (Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India), Binny Bansal of Flipkart (Image: Vipin Kumar/Hindustan Times via Getty Images). Ultra net-worth individuals (UHNIs) from the technology sector, have donated more generously than other sectors.

Clockwise: Abhiraj Singh Bahl of Urban Company (Image: Pradeep Gaur/Mint via Getty Images), Nithin and Nikhil Kamath of Zerodha (Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India), Binny Bansal of Flipkart (Image: Vipin Kumar/Hindustan Times via Getty Images). Ultra net-worth individuals (UHNIs) from the technology sector, have donated more generously than other sectors.

Nikhil Kamath says the reason philanthropy makes sense in today’s world is because the wealth disparity among people is high and is constantly growing. Kamath, 35, the co-founder of stock brokerage company Zerodha, is India’s youngest philanthropist—according to the Edelgive Hurun India Philanthropy List 2021—and has pledged to donate a quarter of his wealth. He plans to give back Rs750 crore over the next three years along with his brother Nithin, the co-founder and CEO of Zerodha. “We are in a position to effect change, so philanthropy is prudent and necessary for us to undertake,” says Kamath.

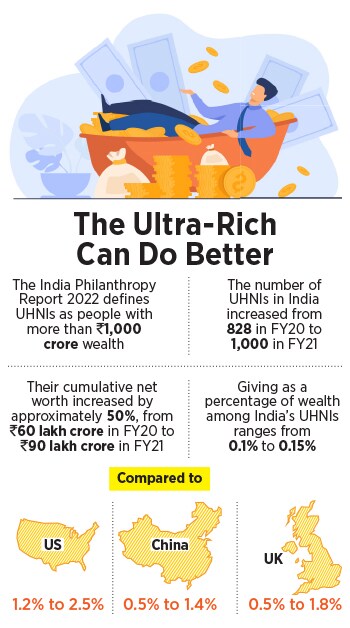

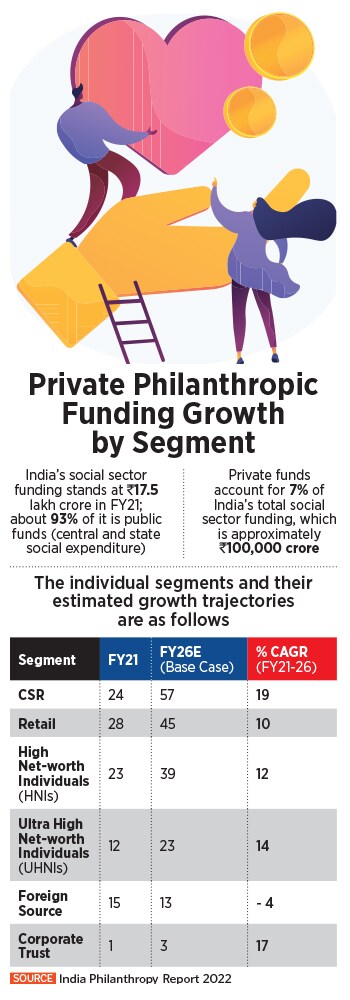

India’s billionaires and the super-rich, however, seem to be some way off from reaching their philanthropic potential. As per the India Philanthropy Report (IPR) 2022 released on Tuesday by Bain & Company and Dasra, as the economic disparity among the top first percentile and bottom 50th percentile of people in India continued to widen, and Covid-19 pushed more than 20 crore people into poverty, overall family philanthropy [giving by ultra high net-worth individuals (UHNIs) and high net-worth individuals (HNIs)] actually contracted.

Those with wealth between Rs7 crore and Rs1,000 crore are categorised as HNIs in the report, while individuals with wealth of more than Rs1,000 crore are UHNIs. The contribution of HNIs has seen a modest six percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR)—from about Rs16,000 crore in FY15 to around Rs22,000 crore in FY21.

This comes at a time when India is facing a glaring

This comes at a time when India is facing a glaring

Srinath says the younger lot of philanthropists have a larger vision than traditional philanthropists. “They also want to be co-creators of social interventions rather than just passive cheque-writers, so they bring to the table their expertise and network to have more agency and achieve more scale.”

Srinath says the younger lot of philanthropists have a larger vision than traditional philanthropists. “They also want to be co-creators of social interventions rather than just passive cheque-writers, so they bring to the table their expertise and network to have more agency and achieve more scale.”