Much ado about something: Women in the world of theatre

The varied representation of women in Indian theatre is symbolic of their real-life efforts to reclaim their voice and space in society

Rajashree Sawant Wad

Image: Punit Reddy

Image: Punit Reddy

Heerabai is a fictional lavani performer in the piece that was scripted by Sushama Deshpande circa 1994. For many years, Deshpande had stationed herself in lavani households, observing the quotidian affairs of dancers, attending their public baithaks, sometimes as the only woman in an audience full of clamorous men. “I just wanted to experience their lives. I was struck by how empowered they were, despite being entangled in a web of exploitation,” she says. This priceless window into their lives resulted in Tichya Aichi..., a play she has herself performed for more than two decades.

While Sawant Wad’s acting chops are amply on display, it is through the classic lavani set-pieces that the play intriguingly opens up a parallel discourse, and lets emerge echoes of other voices embedded in it. In these interludes, Sawant Wad’s playfully coquettish display, the erotic twirl of her nauvari saree, and her shifting expressions, immediately bring to mind the virtuosity of real-life lavani exponent Shakuntala Nagarkar. Indeed, Nagarkar’s name appears in the credits as the play’s choreographer, but she has also recently top-lined a resoundingly successful theatrical show by actual lavani practitioners, which is why her trademark flair is so familiar and so strikingly discernible in Sawant Wad’s faithful rendition.

Image: Kunal Vijayakar

In that production, called Sangeet Bari, Nagarkar appeared alongside the equally formidable Mohanabai Mahalanglekar. In her 50s, Nagarkar is an impossible paragon of seduction, as ecstatic audiences of both men and women watch her enact intricately interactive lavanis. She toys with her audience with the same delicate ease with which she would once regale her ‘customers’. By contrast, Sawant Wad’s ‘performance of a performance’ in Tichya Aaichi… plays itself out to imagined onlookers.

In Sangeet Bari, the writer-director duo, Bhushan Korgaonkar and Savitri Medhatul, supplement Nagarkar’s corporeal eloquence with anecdotes drawn from her life and commentary about the form and its custodians. Because Nagarkar and Mahalanglekar were both subjects of Deshpande’s early scrutiny (although Heerabai is a composite of many performers), it is interesting to see how stories of the same women exchange hands so frequently over the years, passing from an anthropologist seeking to illuminate the lives of the marginalised, to artistes robustly recounting their own tales to a consummate actor seeking a part she can truly relish.

The visibility of women’s personal histories, usually tided over in the mists of time, is an important preoccupation for Deshpande. She has consistently excavated tales that have a particularly strong intersectional thrust.

For instance, in Bayaa Daar Ughad, she draws from real-life accounts of women-saints who lived in Maharashtra between the 13th and 18th centuries. “More than the calling of spirituality, I found that these women were escaping the doldrums of domesticity,” she says of their proto-feminist leanings. Deshpande’s most iconic play—which she has performed for 27 years—is Whay Mi Savitribai, based on the life of the 19th century social reformer Savitribai Phule. And, in the fairly recent Aaydaan, she piquantly dramatises the autobiography of prominent Dalit activist Urmila Pawar.

Deshpande scarcely bristles at the charge that her work is ‘women-oriented’. “We are shaped by the systems of oppression to which we belong. If my work seems predicated by my gender, so be it,” she says. In fact, it is their universal resonance that bubbles to the surface with each staging. The bitter-sweet Aaydaan perhaps cannot alleviate the burdens of the past, but the deep pain of Dalit existence, especially that of Dalit women, comes swathed in an uplift that is undeniably transformative.

While the status quo is all too familiar to women working in the arts, sometimes the distant past holds the key to contemporary innovation. In Thrissur, Usha Nangiar is a rare exponent of Nangiar Kūthu—the form of Koodiyattam enacted by female performers. Over several centuries, the feminine voice has been slowly erased from the traditional repertoire, with men performing both genders. Nangiar had once chanced upon an ancient production manual with an intriguing stage instruction. “It specified that the actress playing Mandodari need not appear on stage,” she says. This indicated the presence of female performers in earlier times. More research resulted in a plethora of other encouraging references.

Over the past decade-and-a-half, this has led to Nangiar creating an anthology of performances in which the female character (whether it is Mandodari, Sita, Soorpanakha, Ahalya or Draupadi) is placed centerstage. Each piece is retrofitted into the intricately gestural grammar of the ancient form. The most celebrated piece in her oeuvre is Draupadi. In this play, she enacts the many men of the Kuru household; but it is in Draupadi’s nirvahana (the flashback) that the feminine psyche comes majestically into its own. “Performing Draupadi in a space in which I also live as a woman is something I derive great strength from,” she says.

A wall of mizhavu drums gives shape to her performance, but as it was for the lavani performers, it is her mudras—patterns of physical performance with a range of meanings and emotions—that is the real literature, of which her body is the prized receptacle. Supplanting the male vantage with a female one spawns works that are nuanced and aesthetically satisfying in no uncertain terms, stripped of the baggage of male privilege. This underlines the tragedy and the travesty of these voices being suppressed for so long.

Of course, one cannot discount the contribution of men to the annals of theatre that are significant when it comes to the representation of women. Looking at more contemporary works, the male gaze is certainly double-edged, and can prove to be both reductive and liberating. Manav Kaul’s work as playwright and director is a semi-autobiographical oeuvre in which the man is the creative force at the centre of the universe. His women invariably appear in the mould of the eternal muse. In the hyperactive Red Sparrow, Nimrat Kaur plays a feisty femme fatale who has leapt out of the pages of a novel. She remembers, “In all that flamboyance, when you write in a female part, more often than not, you want to romance her. It is from a very masculine perspective (but) after a point, I don’t want to resist that.”

In Kaul’s Red Sparrow and Haath ka Aaya... Shunya, Kaur had to physically rough up her men. “It’s something that Manav insists, because it is not expected of a woman. These are not straight-jacketed women. It’s his way of showing a rebellion somewhere or, perhaps, a possibility,” she says. Yet, these unconventional women are rare in Kaul’s plays.

With his new play Chuhal, written purportedly from a female perspective, Kaul seeks to create a new female archetype—Sugandha Garg plays a small town girl who refuses to be tied down by marriage, while embracing a whimsical romantic existence that relies as much on imagination as it does on sexual transgression.

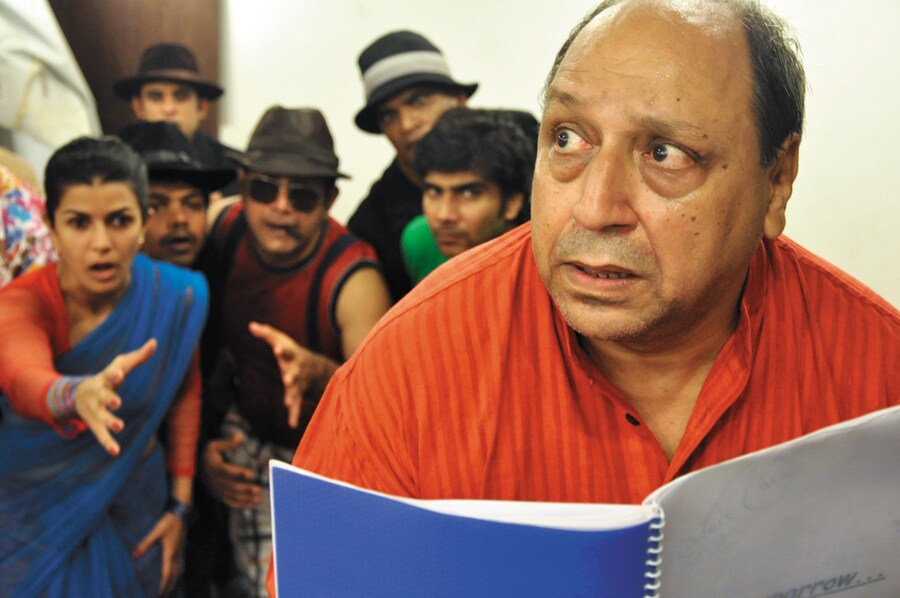

In contrast, the primary archetype that connects the women inhabiting playwright Makrand Deshpande’s plays is that of a nurturing care-giver who, fortunately, is never quite one-dimensional. In Karodon Mein Ek, a daughter-in-law (Ayesha Raza Mishra) play-acts several parts—a nurse, the old wife, a kindly neighbour—to feed an elderly man’s delusions that his growing decrepitude is not real. Raza Mishra’s easy manner deceptively belies the instincts of a fierce (if stoic) protector of a world that is rapidly unravelling. Her equanimity provides the play its essential humanism.

Divya Jagdale (left in the picture) and Ahlam Khan Karachiwala in Miss Beautiful

In Miss Beautiful, an actor (Ahlam Khan Karachiwala) walks in as a ‘daughter-in-law for hire’ into the world of a playwright’s ageing parents, while Divya Jagdale, as his old mother, gives us a good measure of a woman developing an individualistic streak in her advancing years.

In Maa in Transit, Karachiwala is a mother preparing for her final journey that would leave her adoring son stranded in a kind of worldly purgatory. Her refreshing ambivalence towards both death and attachments, without forgoing a shred of empathy expected of a maternal figure, makes her a unique paragon that we don’t usually encounter. Deshpande breathes a lot of agency into his women, but they do seem completely devoid of feminine angst. However satisfying that may be, it is an emancipation that appears to have been too easily arrived at.

Image: Karthikeya Shiva

In S*x, M*rality & Cens*rship, working with the lower-class women from Vijay Tendulkar’s seminal Sakharam Binder, performed as a play within the play, director Sunil Shanbag doesn’t extricate them from social circumstances, but adds nuances of characterisation that elevates them. Geetanjali Kulkarni plays the repressed but scheming Lakshmi who readily submits to brutal beatings from Sakharam, but is never quite a doormat. She says, “[Sunil] made me look at Lakshmi not just as an unfortunate victim, but by trying to understand her sexuality, the fanaticism in her, and the transformation she brings about in Sakharam himself.” The character of Champa, that made the play a flashpoint in the 1970s, is a woman who drinks and beats up her husband in a fit of rage. This is one of Sawant Wad’s iconic parts and she gets it all down, right from Champa’s swagger to the manner in which she participates in her own sexual degradation with unconcealed disgust—her every utterance an indictment of stifling patriarchy.

In Shanbag’s Club Desire, the fetishised feistiness of night-club singer Chaahat allowed lead actor Palomi Ghosh to harness a larger-than-life persona who refuses to disavow her tremendous desires. Shanbag’s outing in 2016 was the Goa-inflected Loretta in which the title character, played by Roslyn Pereira, is immune to the dark forces of commerce and development that appear to corrupt the men around her. This brand of child-like winsome woman flits in and out of our plays, staying resolutely within the confines of theatrical cliché. Unlike Kaul and Deshpande, Shanbag’s plays are written by a roster of writers, but bear his indelible stamp as an auteur constantly negotiating an ethos in which women are quite indispensable. Put together, they form a diverse constellation of characters that are never cardboard cutouts.

The ouevre of the prolific playwright Purva Naresh Saxena also throws up a profusion of atypical women in conventional situations. In Aaj Rang Hai, two elderly women, Beni and Phuphi, struggle with fostering Hindu-Muslim amity at a time when sectarian notions have rapidly gained ground. Karachiwala’s Phuphi wears her prejudices on her sleeve—a Muslim boy isn’t allowed to set foot in her kitchen—but her bigotry is superficial, and at heart she is a woman welling over in empathy. These shades of grey give us satisfying delineated women in Saxena’s other works as well. Keeping her feminine gaze centrestage is something she isn’t defensive about anymore.

Image ( Aaj Rang Hai): Suresh Babu

One trend observed over the past few years is that of an abundance of women theatre-makers who are authoring their own self-authored works that dwell expansively on the feminine condition in ways that are often unpredictable. However tempting it may be to view this through the prism of a feminine renaissance, many makers themselves are resistant, quite rightfully, to being placed in limiting boxes. Their grouping as women is perhaps also arbitrary, but is necessitated by a culture in which such discursive formations continue to persist.

In many of the works, the oppression narrative is clearly eschewed. As theatre-maker Jyoti Dogra puts it, “Gender is never a consideration for me. When I create a work, it stems from my own unique personality. In fact, I have categorically refused to exhibit my work on feminist podiums.” Her Notes on Chai sees her switching seamlessly between male and female characters, positioning them as interchangeable entities equal in spirit. One of Dogra’s prime influences has been Polish theatre director Jerzy Grotowski. In his strenuously physical training, he broke the bodies down to create a stream of somatic expression in which there was no place for gender.

However, where a piece is placed in a pantheon depends a lot on those consuming the material than what a maker intends. “Not ‘seeing’ gender, or moving past it is also feminist,” says Mallika Taneja, whose Thoda Dhyaan Se recently concluded a 10-show run in Mumbai. In The Doorway, when Dogra places on stage her ‘woman’s body’, and talks about its sexuality, the audience cannot escape the notion of gender as representative, rather than specific or individual.

Yet, there is also the vanguard of ‘protest theatre’ in which feminist angst or agenda is worn firmly on the sleeve. Works like Sophia Stepf’s C Sharp C Blunt and Kalyanee Mulay’s Unseen foreground the suppression of women implicating even the men in the audience as voyeurs and chauvinists. These works propagate their ideas as a form of disturbance implanted in the psyche of those held complicit in reinforcing a status quo that has crossed its sell-by date.

However, the shrill tenor of several protest pieces—where victimhood is the weapon of choice and there is no real resolution in sight—can sometimes be self-defeating, which is why labels like ‘feminist theatre’ are not so easily embraced by even those working resolutely in this realm. Taneja’s piece clearly challenges patriarchal norms, but she takes tremendous care in ensuring the message is delivered with an equanimity that does not alienate men. Mulay talks about the anger so implicit in her piece: “The sheer helplessness that I feel about the problems that collectively beset women can sometimes only be released in the form of anger.” Yet, Unseen is not a one-dimensional clarion call, and sees her oscillating between both angst and a self-contained but seething poise, a constant negotiation that women undertake in reality.

It is interesting how gender itself becomes a playground for many of the pieces. Akshayambara, written and directed by the Bengaluru-based Sharanya Ramprakash, introduces a female performer (played by Ramprakash) into the male-dominated world of professional yakshagana. In a remarkable subversion, she plays Duryodhana rather than a character from the limited female repertoire of the form. Yet, Ramprakash does this without creating any illusion of manhood. “That is the most empowering aspect of a performance. When I come on to the stage, and say I am Ravana, people should be ready to go with that,” she says.

Image: Adrien Roche

Also from Bengaluru, Anuja Ghosalkar has written and directed Lady Anandi, based on her great-grandfather, Madhavrao Tipnis, a female impersonator in late 19th century Marathi theatre. It was female impersonators like Tipnis and Balgandharva who first made women visible on stage, even if their accoutrements and manners set in stone standards for femininity that were already unrealistic. Ghosalkar stages the piece as a work-in-progress—part performance, part lecture-demonstration. “The form itself is amorphous, and dispenses with structures and hegemonies that define conventional theatre. That, for me, makes this a piece very feminist in spirit,” she said during a post-show conversation last October.

This spectrum of work is certainly substantial, which is why theatre has earned the reputation of being a creative field in which women are not quite as hard done by. Yet, scratching the surface reveals a grappling with identity and norms that queers the pitch somewhat. In a world with little financial stakes, glass ceilings may not be prevalent in obvious ways, but the tribe of women theatre-makers know very well that they cannot quite take this relative egalitarianism for granted. In turn, this makes the work they generate that much more potent.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X