A Taste Of Cognac

Time moves slowly in Remy Martin vineyards, producers of the finest cognacs for three centuries

The right turn-off to Domaine des Étangs is sharp. My husband, Jaidev, is driving at a clip down the narrow country road and we miss the turn and have to double-back. The tires kick up gravel as he makes a tight U-turn in our rented ice-blue Peugeot. After a two-hour train ride from Paris to Angoulême and an hour of driving, we’re anxious to settle into our new lodgings and begin exploring the Cognac region.

A long, straight road lined with trees made barren by winter leads into the 850-hectare Domaine of the Ponds. We come upon a medieval château, which looks like it materialised out of a fairytale book. It’s the kind of place I dreamed about when I was a child, imagining myself a princess living on her estate in one of the large yellow turrets overlooking the still pond. But this is not make-believe. The Domaine possesses an air of magic: It’s the kind of place where you just might start seeing forest fairies if you stay too long.

We follow signs to the reception next door, a long stone building that also houses the restaurant and five guest rooms upstairs. Inside, it’s warm and rustic, and there is a large fire smouldering in the antique fireplace. The heat warms our bones and my thoughts drift and evaporate like lazy wisps of smoke. This is a completely different world, away from city life, and it takes me time to adjust to the silence. Country silence is a particular type of quiet; it forces you to tune into your surroundings. Senses are heightened. Time slows down.

Our quaint stone cottage is a quick three-minute drive from the reception. I notice an adjoining appendage on the side of the cottage, which resembles a round adobe hut. Upon entering, I realise the fireplace is in front of what used to be a wood-burning oven, the old stove hole leading into the exterior bulge. Worn wooden paddles, originally used to lift bread, are mounted on the wall for decoration. Upstairs, the loft ceiling is low, and I need to duck so as not to bang my head against the rafters above the bed. The only sound I hear is the fluttering of a beetle’s wings brushing against a lampshade.

The next day, having slept like a rock, I’m refreshed and ready to start. We’re visiting Rémy Martin, which has made fine champagne cognac since 1724. Our guide, Micaëlle, is French, but her family is from Africa. She immediately tells Jaidev that she has a deep appreciation of India and its cultures, has visited the Sula Vineyards, and even contemplated living in India.

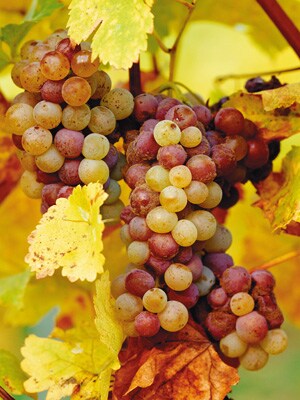

“The centaur is a very important symbol for Maison Rémy Martin,” Micaëlle tells us as she leads the way to the cellar. “The founder was a Sagittarius.” The centaur represents energy, courage, and generosity, traits that embody the spirit of Rémy Martin. “All over the world, cognac is a symbol of French lifestyle,” she says. “Rémy Martin only produces eaux-de-vie from grapes grown in the region’s best vineyards, Grande Champagne and Petite Champagne.” These regions contain a unique chalk-flecked soil that reflects light and ripens the grapes to perfection.

Technically, all cognacs are brandies: Spirits distilled from wine or fermented juice and aged for at least six months in oak casks. But while brandy can be produced anywhere in the world, cognac can only be produced in the Cognac region, just like champagne can only be produced in the Champagne region.

Eaux-de-vie, which literally translates as “water of life”, is a colourless brandy made from ripe, fermented fruit that is run through a double-distillation process. Referring to a small model, Micaëlle explains that eaux-de-vie is produced with a copper still, called alambic charentais, which looks like an apparatus from a scientist’s lab. “Of course, we don’t use a distiller this size, as it is much too small to make the quantities we produce,” she says. “But we do distill in small batches.”

The alambic is of pure copper to withstand the high acidity of the wine; other metals would dissolve. It has three main interconnected chambers: A boiler, a pre-heater, and a condenser.

Grapes are harvested once a year from the end of September to the beginning of October. Farmers are prohibited to water the vineyards, as it might decrease the concentration of flavour in the grapes. First, the grapes are crushed and fermented. This harsh, un-aged (not to be confused with young) wine is siphoned into the alambic’s copper boiler with the lees, the dead yeast cell impurities (such as skin and pips) that are left over from fermentation. The mixture is brought to a high heat, creating a ‘brew’. The brew vapours travel from the boiler through a pipe shaped like a swan’s neck, carrying them past a pre-heater to a condenser coil, which causes the vapour to turn to liquid. This twice-distilled colourless liquid is eaux-de-vie. “Nine litres of wine yields one litre of eaux-de-vie,” Micaëlle says.

The eaux-de-vie is stored in French oak casks made of wood harvested from the nearby Limousin forest — by law, split from the trunk, not chopped. With time, the eaux-de-vie will become cognac. The ageing process lasts at least two years, during which the cognac matures and acquires an amber colour from the tannins in the wood. “Of course, the angels take their share,” Micaëlle says, winking. The liquid lost through the porous barrels is referred to as the ‘angel’s share’.

“Our cellar master has a vast palette of eaux-de-vie to play with, from young to old,” Micaëlle says. “Some of our barrels contain spirits that have been aged for more than a century.” The cognac’s personality is determined when the cellar master chooses which eaux-de-vie will be combined for the ultimate taste, aroma, and body. Mixing different eaux-de-vie heightens the cognac’s complexity and flavour.

“Louis XIII, for example, is composed of a unique blend of 1,200 eaux-de-vie,” Micaëlle says. Known as the King of Cognacs, it pays homage to the King of France, during whose reign the Rémy Martin family settled in the Cognac region.

As we explore the dank cellar, Micaëlle tells us that the original structure was built in 1910. Expansive cobwebs adorn its corners, as if the spiders spun swathes to protect the casks. She removes the cork that plugs a hole in a weathered barrel, over a century old and no longer in production.

“It is perfume that we drink,” she says, as we inhale the aroma of Louis XIII cognac. It is nothing like I’ve ever smelled before, but exactly what I’d imagine an ancient perfume would evoke — an alluring, complex scent that transports one to a different era.

“There have been only four cellar masters at Rémy Martin in the past century,” Micaëlle says. The role of the cellar master commands huge respect globally, because the job demands a special combination of skills: Knowledgeable viticulturalist, skilled wine maker, master blender, and expert taster with a bit of magician. She tells us that Pierrette Trichet, the current cellar master who was appointed in 2003 after 30 years of apprenticeship, is Rémy Martin’s first female cellar master.

Micaëlle treats us to a tasting of Rémy’s VSOP (Very Superior Old Pale) and XO (Very Old). The VSOP is served chilled, which tingles our taste buds, and the XO is smooth and woody. Hors d’oeuvres created by Philippe Saint Romas, the executive chef at Rémy Martin, accompany the tasting. My favorite: Foie gras with pineaux gelée.

Claude Monet once said, “The great thing about making cognac is that it teaches you above everything else to wait.” Monet would bring many canvases outdoors and work on each one for a short time over many days, a testament to the fact that producing things of true quality, whether paintings or cognac, takes time — and patience.

It is a valuable lesson I will take back home with me to New York, where time seems eternally fleeting.

TRIP PLANNER

When to go: With the second highest sunshine hours in France (exceeded only by the Côte d’Azur), Cognac is the ideal region to visit during summer. World-famous cognac houses such as Hennessy and Rémy Martin offer guided tours around their distilleries year-round, but since summer is such a popular time to visit, it’s best to make reservations in advance. For information on Rémy Martin tours and bookings, log on to visitesremymartin.com.

How to get there: The best way is by rail from Paris. The TGV (Train à Grande Vitesse, or high-speed train) from Paris to Angoulême takes about 2.5 hours, and the connecting TER (Transport Express Régional) train from Angoulême to Cognac takes about 45 minutes. The roundtrip ticket in economy should cost around Rs. 10,700. Visit raileurope.com for booking information. If you decide to rent a car in Paris, Cognac is 463 km, about five hours’ driving. Alternately, if you transfer via the UK and do not wish to visit Paris, you can fly directly into the Angoulême airport.

Where to stay: If you’re searching for serenity in an idyllic country setting, look no further than Domaine des Étangs (domainedesetangs.fr), where you can cycle, take a rowboat out on one of the many ponds, or just relax in nature. Stay in one of the cottages sprinkled across the Domaine, or lodge in one of the main building’s five apartments (Rs. 10,400 - Rs. 39,000). Close to the centre of Cognac, Domaine du Breuil (hotel-domaine-du-breuil.com) is an excellent option. Set on a beautiful 7-hectare park, this 19th century Louis Philippe-style château has 24 charming rooms with modern facilities. There is a lovely garden and an outdoor heated swimming pool to enjoy in the summer (Rs. 4,300 - Rs. 10,000). One-and-a-half miles from Cognac’s centre near the banks of the Charente river is Château L’Yeuse (yeuse.fr), which has a large terrace boasting panoramic views of the countryside. Guests can indulge in the hotel’s spa, and enjoy the local golf course (Rs. 6,900 - Rs. 23,600).

Where to eat: Many hôtels offer farm-to-table restaurants featuring fresh local ingredients. Domaine des Étangs offers an impressive five-course tasting menu featuring fresh daily fare, including mushrooms found in the Domaine’s forest, Jarnac truffles, Limousin beef, and Belchard apples (Rs. 2,020, drinks not included). Hostellerie Les Pigeons Blancs, (pigeons-blancs.com) run by the Tachet family, is a gastronomic restaurant with two elegant dining rooms, exposed ceiling beams, and limestone fireplaces. Menu offerings are subject to ingredient availability, but expect champagne-flavoured cream sauces and seafood steamed with cognac vapours. The ‘Menu Noblesse du Patrimoine’ is Rs. 3,700, and the ‘Création du jour’ menu is Rs. 2,150. Moulin de Cierzac (moulindecierzac.com) occupies a former 19th century mill house and sits adjacent to a stream. Homemade foie gras, a signature dish, is marinated in cognac, sauterne, and white port, wrapped au torchon (in a napkin) and then poached. The ‘Menu of the Lodging House’ is priced at Rs. 2,840 and the ‘Jacquet menu’ is Rs. 1,890. No matter where you dine, ask for a pre-supper ‘Pineaujito’, a native cocktail made from local Pineau liquor and mixed like a mojito.

How to get around: Once you’re in Cognac, it’s ideal to rent a car. Economy car prices start around Rs. 8,000 per day in high season. Taxis are expensive: Note that when called to pick up passengers from a location, taxis add the cost of that journey to the fare. Many attractions located in vieux Cognac (old Cognac) are accessible by foot and can be reached by a 10-15 minute walk. Rentinga bike is also an excellent get-around-town option. A five-day couples bicycle package runs to Rs. 6,300, and a family package runs to Rs. 9,450. Call +33-545652186, or visit bikehiredirect.com for booking information.

What to see/do: A tour of Rémy Martin is, of course, not to be missed. Other cognac producers are also worth a visit, including Hennessy, Martell, and Camus, where you can create your own cognac blend (price varies by producer and type of tour). If you’ve had your fill of eating and drinking, get your culture fix at Musée des Arts du Cognac (musees-cognac.fr), which features Cognac-related paintings, vintage advertisements, and Cognac production tools such as an oak press from 1760. The museum is a 10-minute walk from ‘la place François’ in old Cognac, and tickets are Rs. 315.

To see the city from another vantage point, take a cruise on a gabarre, a traditional flat-bottomed oak boat that was once used to transport cognac and salt, and now transports visitors along the Charente river. Tickets can be bought at the Maison des Gabarriers (village-gabarrier.com) in the village of Saint Simon near Angoulême for about Rs. 400, which includes admission to the Maison des Gabarriers museum. Located on the banks of the Charente between Cognac and Jarnac, the Golf du Cognac winds between vineyards, woodland and three ponds. Green fees start at Rs. 4,000 and reservations must be made in advance (+33-545321817).

What to shop for: The French writer Victor Hugo called cognac the “liquor of the gods”, and a bottle of this renowned spirit is a must-have souvenir. Rémy Martin bottles run the gamut and are priced from Rs. 3,150 to Rs. 1 lakh. Most cognac producers have a boutique carrying a full range of their products. Visit La Cognathèque (cognatheque.com) for a wide range of lesser-known quality cognac producers and an array of interesting decanters.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)