How to Handle Delhi's Influx of Migrants

The heavy influx of migrants is choking the capital. Though solutions were identified long ago, lack of vision and adequate funds are pushing the city to the edge

In his award-winning documentary Last Train Home, director Lixin Fan draws attention to the plight of migrant Chinese workers living in far-flung industrial cities and the strain they inflict on the country’s infrastructure when some 130 million of them make their annual journey back home for the Chinese New Year. It’s a film that highlights the social costs of the Chinese economic miracle. It’s a film about disillusionment and displacement. It’s a film that could be made just as easily in India.

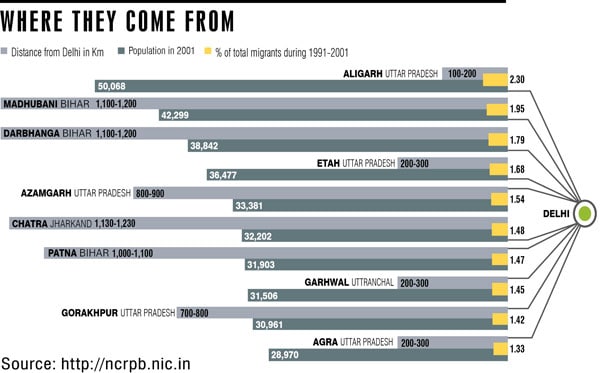

In the absence of opportunities in rural India, it’s a given that the poor will flock to the cities in search of jobs and a better life. This puts enormous strain on the already fragile infrastructure in these cities. But nowhere is the problem more acute than in Delhi, which has little place left to expand into and attracts migrants from practically the whole of northern India. It’s also becoming prohibitively expensive.

To make ends meet, more and more people are choosing to live in the neighbouring states and travel to Delhi for work. In some cases, the commute is more than 100 km every day. Take the case of Ravi Shanker. Five years ago, Shanker, 35, got a job as an assistant with the tribal affairs ministry. He planned to bring his family to the capital, but found the cost of living extremely high. So, he decided to set up his house in his hometown Meerut and instead travel six hours daily to his workplace.

“It is very demanding but I think it is not viable to live in Delhi and bring up a family. It’s just too expensive,” he says. He may be unaware of it, but Shanker’s ‘art of living’ is advocated by the planners for Delhi who are trying to tackle the alarming rise in migrant population.

More than two lakh people make Delhi their home every year, forcing Chief Minister Sheila Dikshit to recently warn that the city’s population, if unchecked, could touch 1.6 crore in 2021, a significant rise from the 1.3 crore now.

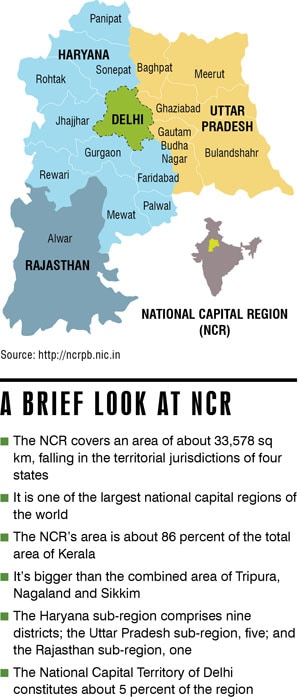

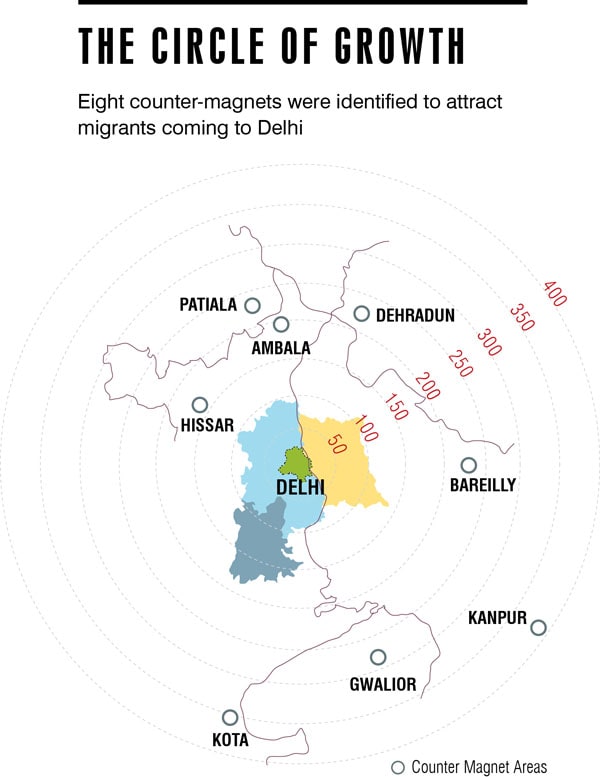

And it’s not like the planners didn’t anticipate the problems. After all, it’s been more than 25 years that they first tried to tackle the issue. They realised that to stem the tide of migrants into Delhi, they needed to develop the National Capital Region, an area surrounding Delhi and covering four states, and develop ‘counter magnet areas’ in neighbouring states so that people looking for jobs would be attracted to them instead. The National Capital Region Planning Board (NCRPB) was formed in 1985 for this purpose.

The NCRPB, which functions under the Union urban development ministry, gives soft loans for projects it recommends. It identified Bareilly, Hissar, Gwalior, Kota, Patiala, Ambala, Kanpur, and Dehradun as the counter magnets. But in the decades since, little has improved. If anything, things have progressively gotten worse.

The Issues Are Many

The NCRPB faces three major issues when it comes to executing its plans. First, it does not have enough money. While it advises other states on how to develop the counter magnet areas, the states in return expect it to fund the projects it recommends. But the NCRPB just doesn’t have the funds to do so. Second, the plans involve towns and cities in other states (Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Rajasthan, among others), and the governments there may not always have the best interests of Delhi in mind, particularly when they have other, more important, regional problems to deal with. Third, the vision conceived by the NCRPB even for the capital region is narrow in its scope, flawed and out of touch with reality.

In Hissar, the NCRPB funded a water supply project for about Rs. 16 crore — one of the more than 255 projects that the board has funded for a total Rs. 5,000 crore over the past 10 years. This is hardly enough.

City planning experts say the board needs to spend at least Rs. 2,000 crore every year to build world class infrastructure in NCR alone. This is not taking into account the massive investments required to develop the counter magnet areas.

“The projects they have funded are miniscule when compared with the future needs of this region and the advisories are not backed by funds. Unless the NCRPB has the resources to back these ideas, what is the point in suggesting to the states to take up these projects,” asks infrastructure expert Partho Mukhopadhyaya.

N. Sridharan from the School of Planning and Architecture, Delhi, agrees. “If you take the developing areas around Delhi into account, we are possibly talking about a Paris of the future. But the NCRPB is a toothless body and does not even have the resources that would be required to plan on such a massive scale. How can these small-sized water and road projects be called vision?” he asks.

Growth Pangs

Despite all this, there is substantial investment pouring into NCR. A recent survey by hospitality consultancy, HVS, reveals that the NCR will have one of the fastest growth rates in the country for the hospitality sector. Not surprising, since over the next five years, some of the largest hotel chains in the world — Four Seasons, Hilton, Marriott, Hyatt, Intercontinental, Accor and Starwood, among others — are planning to invest in NCR.

That’s not all. The Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor is expected to attract investments of over Rs. 4 lakh crore and a part of it will be situated in NCR and areas surrounding it.

Experts point out that policy and administrative action had little to do with NCR’s growth. Historically, the demand for housing in the adjoining districts of Delhi was driven mainly by the scarcity of land within the city. It was not planned. For many years, private builders couldn’t develop properties in Delhi because there was hardly any free land left. It was only when the mill lands were freed around 10 years ago that builders began to construct apartments, office complexes and shopping malls.

“The FSI (floor space index) ratio in Delhi is also stringent which means that the potential for vertical development is limited,” says Sridharan. This led to the demand for housing in Noida in Uttar Pradesh and Gurgaon in Haryana.

Akhileshwar Sahay of Feedback Ventures says there is a need to build on this growth and ensure that roads and other transportation links are in place.

So, what are the NCRPB’s plans for the region? NCRPB officers talk of high-speed trains that will transport people to Panipat in Haryana, Meerut in Uttar Pradesh and Alwar in Rajasthan within an hour. Today, it takes more than three hours to travel to these places. “We have signed MoUs (memorandums of understanding) with the state governments concerned. It will happen,” says Rajeev Malhotra, chief regional planner of the NCRPB.

However, officers involved in town planning in Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Haryana say it’s difficult to take such claims seriously as they are not backed by financial commitments.

An official from Uttar Pradesh recalls that last year a group of officers from the state’s power ministry went to Delhi to buy equipment for improving transmission. Since most of the places covered under the project fell in areas abutting Delhi, they tried to raise the money through the NCRPB, which sat on the file for six months.

“The power department needed to modernise its infrastructure in these areas before the summer and here they were being told to wait endlessly. Finally, we told the planning board that we could not wait any longer and raised the money from another source,” says the officer, who did not wish to be named.

Similarly, bureaucrats in Rajasthan accuse NCRPB of shortchanging them. Ten years ago, the NCRPB suggested that Kota be developed as a counter magnet, but so far they have not received any funds for the plan, which includes the development of townships, new industrial clusters as well as the setting up of educational facilities.

“The Centre wants their baby to be nurtured by the states. They want us to solve the problem of congestion in Delhi but without giving us any funds to develop our districts,” says Pradeep Kapur, a senior official with the town and country planning department in Rajasthan.

Uncertain Future

City planning experts say the administrative set-up needs radical changes if the situation is to be rectified. Some even go as far as to recommend doing away with the NCRPB. “It is time for the government to do away with the plan body and consider establishing a megapolis government that will have the necessary powers to plan for the holistic development of the region,” says Sridharan, who advocates carving out districts from Delhi’s neighbourhood and merging them with the capital.

Sahay also agrees that if the government is unable to fund projects in NCR, then it must change the system of administration. “The government needs to plan big and develop industrial clusters in these areas and for that there has to be more resource mobilisation,” he says.

Though the situation is alarming, the NCR has not been entirely unsuccessful. While the population of Delhi has grown by about 21 percent in the last 10 years, in places such as Noida, Faridabad, Gurgaon and Ghaziabad it grew at least 31 percent. This clearly shows that the new growth centres are helping to decongest the capital and take development to a larger region. But the growth is haphazard and unplanned, a combination that could prove to be disastrous for Delhi and the NCR.

Already, the effects are evident in many parts of the capital, especially slums. Sangam Vihar, one of the biggest slums in India, has no water supply in many areas. “Many of my neighbours have sold off their homes to go back to their villages. But for every man who leaves this place in frustration, several more arrive,” says Pramod Mittal, a shopkeeper in the area.

The local MLA (Member of Legislative Assembly), S.C.L. Gupta, says the migrant situation here is already out of control. “Every day thousands of people arrive here seeking work and a cheap place to stay. There is no water, and power supply is also limited. Unless, the surrounding areas of Delhi absorb some of these people, it is going to get even more difficult.”

The situation is grim, but the residents are taking matters into their own hands. About three years ago, some individuals joined hands and decided to hook a pipe to the stem of a bore-well installed here. This pipe was then connected to a network of smaller pipes that carries the water into their homes. The residents pay for the upkeep and maintenance.

Every home in the neighbourhood is now assured of water for 24 hours every 15 days. Unless the planners do something fast, the resilience of the migrants will mean that more of them will find a way to survive inside the city.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)