Sun Pharma's Dilip Shanghvi has become the stuff of legends

Sun Pharma's growth in the last five years cannot be ignored. And neither can its founder-leader Dilip Shanghvi who has become the stuff of legends as he continues to grow and consolidate his Rs 16,080 crore company across the world

Award: Entrepreneur for the year

Dilip Shanghvi

Founder and Managing Director, Sun Pharmaceuticals

Age: 59

Interests outside work: Reading management books. He has just finished How I Did It: Lessons From The Front Lines of Business, a compilation of essays from the Harvard Business Review. He also loves watching Hollywood action movies

Why he won this award: For creating India’s most valuable pharmaceutical company from scratch. And for building one of the most profitable generic drug-makers in the world

Dilip Shanghvi, 59, would like to drive out to the multiplex near his Juhu home and catch the latest Hollywood action movies—just like any other guy. The problem: He isn’t any other guy. “It is getting to be a bit of a bother these days,” he tells Forbes India. People are beginning to recognise the quiet, bespectacled founder of Sun Pharmaceuticals and often point him out to each other. He did manage to watch The Expendables 3 with his family one weekend last month. The franchise that features a veritable who’s who of ’80s action heroes, including Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, Harrison Ford and Jason Statham, is just his kind of movie, says Shanghvi. But he knows that at the rate he is going, he may well have to start watching these thrillers at the mini-theatre in his home. Anonymity is no longer an option. And there are many reasons why.

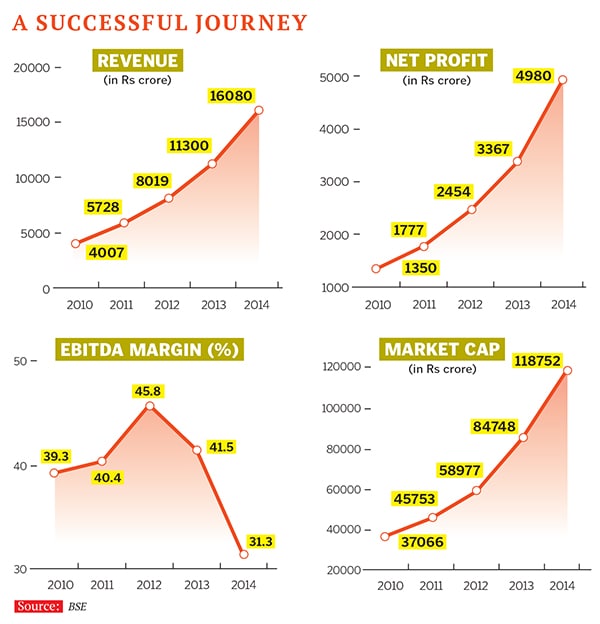

At Rs 16,080 crore revenue, Sun Pharma is now India’s largest pharma company, with 25 manufacturing facilities across four continents. Shanghvi is also the fifth largest complex generics maker in the world. Sun Pharma has grown to be the country’s largest pharma company in the US market, expanding through acquisitions almost every year. All of this has propelled him to the position of India’s second wealthiest entrepreneur, after Reliance Industries’ Mukesh Ambani. With a net worth of $18 billion, Shanghvi out-ranked the far more visible Lakshmi Mittal on the Forbes India Rich List this year.

For investors, though, the real achievement is in the margins that Shanghvi and his team have been notching up. And the higher margins come from international markets, as do three-fourths of his revenues. The company, which prefers to call itself a complex generics maker, has wowed the markets with Ebitda (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) margins of over 30 percent every year (see chart on page 49). On this count, too, it is on top of India’s pharma league-tables. While peers are valued at three to four times their revenue, Sun Pharma trades at close to 11 times its sales.

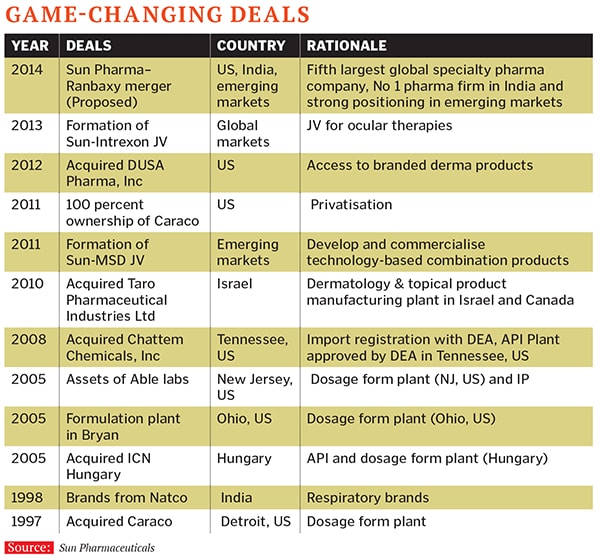

Once complete, the Ranbaxy acquisition, announced in April this year, will add significantly to Sun Pharma’s value. The all-stock deal is proposed at an enterprise value of $4 billion. Meanwhile, Sun Pharma is still sitting on cash reserves of $1.3 billion, and the market expects more acquisitions.

This heady momentum means that Shanghvi will have to forego more than just a low profile as he navigates Sun Pharma to the next level. Because, quite unlike the past, he will now have to decentralise decision-making and authority to manage the colossus that his company has become. Today, much of his time is spent in creating what he calls “a capable and appropriate structure” for the ever-growing company.

The Launch Pad

Shanghvi’s story is fairly text-book. The son of a pharmaceutical wholesaler, he would read patient information leaflets as a boy in Kolkata—and this sparked an interest in medicines.

After finishing his education from the University of Calcutta (he has a bachelor’s in commerce), he moved to Mumbai at the age of 27. With barely Rs 10,000 in his pocket and some experience at his father’s business, he started his own journey in 1983, at a time when multinational pharma companies held sway over the Indian markets. Shanghvi began Sun Pharma with a small but niche portfolio of five products: These included psychiatric drug Lithosun, which the company still makes. The first factory came up at Vapi in Gujarat soon, and he never looked back.

For over two decades, till 2008-09, Sun Pharma grew at a brisk pace but largely by replicating its early success. In India, Shanghvi and his team had pioneered therapy-focussed divisions (business units that concentrated on a single disease type, for example, cardiovascular, ophthalmology or cardiology), so that they could concentrate on sales to a particular set of doctors. The divisions were created based on market feedback; each had a different logo and name and functioned almost like a separate company. As Sun Pharma made deeper relationships with doctors, and began introducing new therapies, sales began going through the roof. Divisions that typically grew at 30 percent every year were scaling up at 60-65 percent.

Up until 2009-10, the company was run by a close-knit team, largely out of its Andheri office in suburban Mumbai. Like most Indian owner-entrepreneurs, Shanghvi led every major activity, and the buck pretty much stopped with him.

“Everyone in the senior team spoke Gujarati, and most of us, including the heads of sales, business development and research, had worked with him for a long time,” says Abhay Gandhi, CEO—India business—Sun Pharma, who headed sales and marketing at the time. He even jokes that Shanghvi probably hired him assuming that he was a Gujarati—which he isn’t. Most meetings were informal and held around Shanghvi’s table. “Decisions were quick,” recalls Gandhi who, along with his team, has been responsible for building relationships with specialist-doctors in India—the folks who have over the years learnt to prescribe therapies sold by the company.

Shanghvi had built Sun with a single-minded focus on chronic drugs (usually prescribed by cardiologists, psychiatrists, neurologists, diabetologists, etc), even though they constituted only 10 percent of the Indian market at the time. Very early in the journey, he took a contrarian bet, eschewing acute therapies (anti-infectives that can be bought over the counter) in favour of chronic. Sun now has about 500 such brands in the market, being sold by its 21 divisions. And its relationships with specialist-doctors are the envy of the industry.

As lifestyle diseases grow in a rapidly urbanising country, the share of chronic therapies has risen. Chronic drug sales are now almost a fourth of the total sales in India. And Sun Pharma has a first-mover advantage over rivals that entered the fray later.

They did make an attempt at antibiotics at one point, says Gandhi, but realised that it was too late to create an anti-infectives business since it was a category where others were very strong. They thought it would be better to buy a company that was doing this. (And they did so early this year when they bought Ranbaxy.)

But even as the pace in India was intensifying, Shanghvi started sensing huge potential in his US business. This was in the early 2000s, when Sun Pharma had begun to build a presence there, particularly in dermatological products. The $300 billion US market has attracted generics drug-makers from all over the world, but Sun Pharma was able to find a foothold with differentiated products, and a keen understanding of the reimbursement process. Unlike in India, pharma companies in the US are not allowed to pitch directly to the doctors. They have to deal with insurance companies, who pay half the cost of the medicines and also decide how much patients will spend on a particular drug. A key aspect of selling in the world’s biggest market is to work with these insurance companies on the one hand and the US FDA (Food and Drug Administration) for an elaborate product filing and certification on the other. The regulator enforces compliance on the quality of drugs sold in the US.

Sun Pharma had first started out as an exporter, and gradually upped its game in the country. Its entry vehicle was when Shanghvi bought Detroit-based Caraco Pharma in 1997, with the intention of increasing production in the US. It took him about a decade to turn around the company, and yet compliance was hard. The plant ran afoul of the US FDA in 2008 and Sun Pharma had to shut it down and work on remediation. Fortunately for Shanghvi, he had made another bet in the country, on NYSE-listed Taro Pharmaceuticals. When he began making a play for it in 2007, Taro was loss-making. Shanghvi was able to wrest control of the company over the next four years, and it has proved to be a great asset. It now accounts for half of Sun Pharma’s US revenues.

His team had also started filing for permissions to sell new generic products on its own steam from 2003-04 onwards. The process is now institutionalised. But, unquestionably, Sun’s US business would have looked very different were it not for Taro.

The Globalisation Trigger

Globalisation was a huge challenge for Shanghvi (and Sun Pharma) in the early years. His business is known for its proclivity for consolidation.

“As he grappled with problems of integration with acquired companies, his understanding of international businesses increased,” says Anubhav Aggarwal, a pharma analyst at Credit Suisse who has tracked the company closely.

Even as Shanghvi sewed up the complex deal to buy Taro Pharmaceuticals from its Israeli shareholders in 2009-10, he was acutely aware of the need for a strong, distributed management team to make decisions in an organised manner.

Kal Sundaram, the then India head of GlaxoSmithKline, had been Shanghvi’s friend and confidant for close to 15 years. The two typically caught up once every few months, often for a quiet dinner at the Taj Lands End in Bandra. Sundaram is a suave, dyed-in-the-wool, big pharma professional who had spent many years working all over the world. Shanghvi, who comes across as quiet and reserved, is extremely well-connected. Those who have known him for a while speak of his excellent network that includes several politicians. He sees a variety of visitors from 10 am to 5 pm, whenever he is in his office. Time after 5 pm is set aside for internal meetings.

Shanghvi realised that an entrepreneur can start a successful business, but needs good managers to scale it up. He was able to convince Sundaram, who is a year older than him, to join Sun Pharma as its India CEO. He followed this key appointment with other lateral hires in senior positions.

Sundaram, who later moved on to head Sun Pharma’s Taro business, has allowed Shanghvi to take a step back from it. “The trick is to be able to retain the entrepreneurial spirit and yet have the ability to scale up when needed, say, from $5 billion to $15 billion,” Sundaram says, joking that “Dilip is training himself to let go but the result is often three steps forward and one back”.

One of the steps forward was to get Israel Makov, a technocrat and former president of Teva Pharmaceuticals, to head the Sun Pharma board. Shanghvi surprised India Inc when he stepped down as board chairman in mid-2012, bringing Makov into the position.

“Israel [Makov] is the big-picture, strategy guy, while I am far more familiar with the specifics of the pharmaceutical industry. We have complementary skills,” says Shanghvi. Analysts say it was Makov, with his substantial network and sharp understanding of the global pharma industry, who initiated talks with Japanese company Daiichi Sankyo for the Ranbaxy acquisition. They expect him to lead Sun to more ambitious buys in the coming years.

Ranjit Shahani, managing director of Novartis India, has been Shanghvi’s peer in the pharma industry for about three decades now. “Bringing in Makov as his boss was a masterstroke by Shanghvi,” says Shahani, who expects the benefits of this strategy to play out globally over the next few years.

When Forbes India caught up with the 75-year-old Makov in September when he was in Mumbai for a board meeting, he said that “the ability to deal with complexity will be Sun’s biggest challenge”.

“Sun has to build itself to be able to deal with the future. We are constantly training/upgrading managers and making systems more transparent,” he said. One example is the establishment of a key M&A team headed by Chief Financial Officer Uday Baldota. This group tracks companies that can be potential acquisitions or licensing partners for Sun.

Makov emphasises on the need to build management capability, so that Sun Pharma can deal with, and respond to, issues quickly.

“Many companies have failed because they couldn’t build this,” he said. And under his tutelage, Shanghvi is learning to delegate. For a hands-on entrepreneur who has always rolled up his sleeves and got down to solving problems, this is not the easiest of jobs.

Quality Is The Answer

Insiders say one recent change has been Shanghvi’s new-found tolerance for consultancy firms. Never one to trust outside advisors to tell him how to run his business, many were surprised when Sun Pharma hired McKinsey & Company to advise the company on key aspects of the merger with Ranbaxy.

The process of integration has already begun in terms of mapping out people and their capabilities. Sun Pharma and Ranbaxy have about 14,000 employees each on their rolls, and redundancies are expected, though Shanghvi has said no one will be fired.

When reminded of his disdain for consultants, Shanghvi says, “The cost of making a mistake now is much higher than before. We are doing many of these things for the first time. If others have done it before, it is better to learn from them rather than make our own mistakes.”

One major and very public concern is the ability to adhere to quality standards set by regulators—or what the pharma industry euphemistically terms ‘compliance issues’. In January this year, the US FDA banned Ranbaxy from exporting products from its Toansa plant in Punjab. This stricture came after similar clamps were put on its factories at Dewas (in Madhya Pradesh) and Paonta Sahib (in Himachal Pradesh) on charges of data fudging last year. In March, in a severe blot to Sun Pharma’s reputation, the US FDA issued a similar import-alert letter to Sun Pharma, prohibiting exports from its plant at Karkhadi in Gujarat. The stricture was issued after a very strongly-worded inspection report of the facility.

Shanghvi says regulatory standards are changing globally and Indian companies have yet to recognise this. “We are still playing catch-up,” he says grimly. As a company, Sun Pharma wants to create a zero-tolerance mechanism for non-compliance, he adds. To this end, it is working with external consultants who are auditing and evaluating the factories and the processes. Some analysts fear that the exercise of sorting out Ranbaxy’s quality problems could prove to be a minefield. But Shanghvi says he is confident. “My understanding is that the issue is more of processes at the Ranbaxy facility. There were no issues with the facility,” he says.

Not everyone is as optimistic. Stock market analyst SP Tulsian says he is quite apprehensive about the run-up in Sun Pharma’s stock price since the Ranbaxy deal was announced. “The sudden movement in just a few months makes me uncomfortable,” says Tulsian. “It seems unjustified unless substantial improvements happen in Ranbaxy’s operations.” Sun Pharma has moved up 27 percent in the last three months, rising to Rs 807 (September 26) from Rs 635 (June 26), while the Sensex has risen six percent in the same period.

Scepticism doesn’t worry the acquisition veteran. Shanghvi has made nine acquisitions in as many years. And unlike Indian entrepreneurs such as Lakshmi Mittal, who are known as turnaround specialists, not all of Shanghvi’s acquisitions have been of badly-run or loss-making companies. In 2012, Sun Pharma acquired Dusa Pharmaceuticals, a skincare speciality company, for $230 million (Rs 1,251 crore). Shanghvi says many of his peers were surprised by how much Sun paid for it ($8 per share, a premium of about 38 percent on the prevailing stock price).

“But we believed we could run it better than how it was [being run]. And we will get back the money in five-six years,” he says.

An earlier acquisition of Tennessee-based Chattem Chemicals, made in 2008, was also approached similarly. The venture has since expanded its production of active pharmaceutical ingredients. “We decided early last decade that the US was a great opportunity. If the potential was good, finding capital was not a problem,” says Baldota.

Also, since ensuring continuity was paramount in both these cases, there was hardly any change in the top management. Shanghvi says an acquisition is worthwhile only if Sun is able to add value. Referring to Ranbaxy, he says, “If a company is not doing well, it doesn’t necessarily mean that it is not a good company”, adding that he is particularly optimistic about the people that Ranbaxy already has on its rolls.

The Future Is Innovation

Shanghvi’s vision is for Sun Pharma to become more global and profitable in the coming years. But the ground reality is that the generics industry is very price sensitive. It is often compared to a leaky bucket through which margins keep falling as more players start making the same drug. However, very few generics makers are able to cross over to become innovators—the entry barriers are simply too high. Shanghvi says the cost of developing a new drug for diabetes could range from $600 million to $700 million over 10 to 15 years.

“This kind of time frame and investment is beyond our horizon. We have to attack problems that we can financially and technically manage,” he says.

Sun Pharma’s strategy to beat this has been to focus on incremental innovation; on developing what are called complex generics. These are generic drugs tweaked for improvement, for example, with better delivery mechanisms so that they are more effective for patients. “Not every generics-maker can do it, and Sun has reaped the benefits of many such innovations in the US,” says Kirti Ganorkar, head of business development.

He cites the example of Sumatriptan, a drug used to treat migraine. GlaxoSmithKline was the originator of the drug which Sun Pharma was able to successfully improve using a more effective auto-injector. Sun Pharma now sells more of this drug than GlaxoSmithKline does.

These drugs too have to go through the whole spectrum of trials. “We began work on Sumatriptan from 2003 onwards, and were able to enter the market only in 2011,” says Ganorkar. Sun Pharma had started filing abbreviated new drug applications (called ANDAs) with the US FDA since 2003. It has now approved ANDAs for 350 products while filings for 140 products are still pending approval, including 12 tentative approvals.

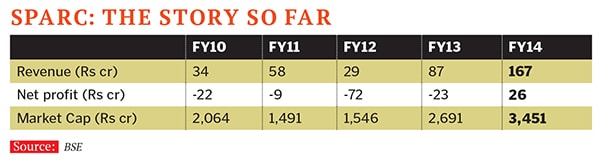

“Investing in innovation has been an early decision right from the time it was a startup,” says Dr T Rajamannar, who has headed research at the company since the early days. He is also a director on the board of Sparc (Sun Pharma Advanced Research Company), a separate pharma research company carved out by Shanghvi in 2007. Sparc, a listed company in which Shanghvi and his family own close to 67 percent, carries out the basic drug discovery and innovation.

Sparc’s record has been patchy so far. Its most talked-about product Starhaler, an inhaler device for asthma patients, bombed in the market and had to go back to the drawing board for improvements. Sun Pharma’s R&D expense is roughly six percent of its sales.

But future innovation need not be homegrown. Both Makov and Shanghvi have begun scouring the world, plugging into startup innovators. “We have to work with universities, professors and smaller research companies who know more than us,” says Shanghvi.

Globally, big pharma is developing deep links into laboratories doing such work. Venture capital firms specialise in sussing out the ones with the most promise and fund the initial trials. And Sun Pharma is looking to tap into these networks. They are also looking for licensing deals with big-pharma innovator companies.

Makov says the pharma industry world over is facing problems of declining productivity of innovation. Breakthrough cures have been too few and far between. He believes that generics companies can spur innovation.

“We have begun challenging patents, and don’t wait for them to expire. The life expectancy of a drug is reduced and this can enhance more innovation,” he says. Makov predicts big changes in the next few years as the global industry evolves to the next generation biological drugs.

Shanghvi, too, is aware of a changing future—in more ways than one. And, to address that, he is spending a significant amount of time on ensuring perpetuity in his business.

Currently, Shanghvi is managing director at Sun Pharma, with various country heads, such as Sundaram and Gandhi, reporting to him. He also continues to be hands-on though senior colleagues say he now relies far more on the top management team. For instance, earlier, he attended every new product meeting—and the company launches nearly 25 to 30 new products every year.

Now, scheduled meetings with the managing director are only once a month (many times on conference call). A senior management team of 10-12 people now manages the day-to-day business, allowing Shanghvi to look at broader things.

Baldota, who works closely with him, says he hears a lot more of “can you get this done” compared to the past when his boss would sit down and sort out the problem himself.

Both Shanghvi’s children, Aalok, 30, and Vidhi, 25, work at Sun Pharma. Aalok heads the business in the rest of the world (markets apart from India and the US). Vidhi, a Wharton grad, is handling one of the diabetology brands. She is also working towards starting a new firm that will deal with medical nutrition products. Shanghvi is keen on encouraging this. “I want them to have an appreciation of the pain involved in building a business. They shouldn’t take things for granted,” he says.

Shanghvi and his family currently own 64 percent of Sun Pharma: Does he ever think of selling out? What if the price is right, we ask. He responds with a counter-question. “Why will I sell out, if I can run it better and create more value? Besides,” he adds wryly, “I really haven’t sold anything in all these years—except maybe a few cars.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)