Shea: The better butter

It has not just changed the way we eat chocolate and moisturise our skins, but the manner in which women live in the heart of Africa

.jpg) Shea butter, extracted from shea nuts, is used in the food and cosmetics industries

Shea butter, extracted from shea nuts, is used in the food and cosmetics industriesPhotographs: Jessica Sarkodie for The Body Shop

It is winter in Mbanayili. The temperature is nudging 37 degrees Celsius, as the sun beats down on the dusty, red earth of this village in northern Ghana. It is late morning when the women gather in the shade of two giant kapok trees, soon filling the air with their lilting voices and clapping. They sway and twirl, in circles and with each other, singing, “Let the light in”.

Taking time out for singing and dancing is not something they can do often. After tending to their husbands’ farms, their children and attending to household chores, there isn’t time for much else. In this rigid patriarchal society where, traditionally, women have barely had a say in any matter and have endured abuses in many forms, the voices of these women now ring louder than they have before.

Thanks to the humble shea.

The shea tree, indigenous to western Africa, grows naturally, unlike plantation crops grown in humid high forest zones, like palm oil, rubber and cocoa. The fact that shea trees take between 15 and 20 years to grow fully, and bear fruit, makes them financially difficult to farm. The fruit of the tree—comprising a thin tart pulp, and a large oil-rich seed—has been traditionally gathered by rural women to make shea butter, which they sell in local markets, and use themselves, either as a cooking medium or to moisturise their dry skin against the heat and dryness of sub-Saharan Africa. The meagre earnings from its sale supplement the earnings from farming, which sees only one harvest a year in the tropical country.

“Income from shea is modest by comparison with palm oil, but its significance for livelihood security is enormous,” says a November 2018 report by AAK, formerly AarhusKarlshamn, a Swedish-Danish company and producer of value-adding vegetable oils and fats. “Generally, this income passes through the hands of women to support expenditure on household essentials. It fills a critical income-gap at the start of the rainy season, when food stocks from the previous annual harvest are low and the current season’s crops are yet to yield.”

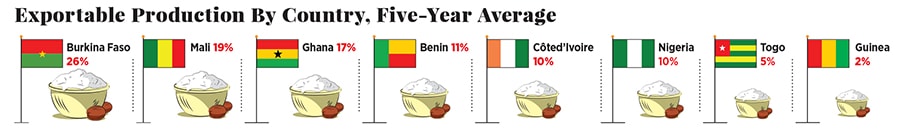

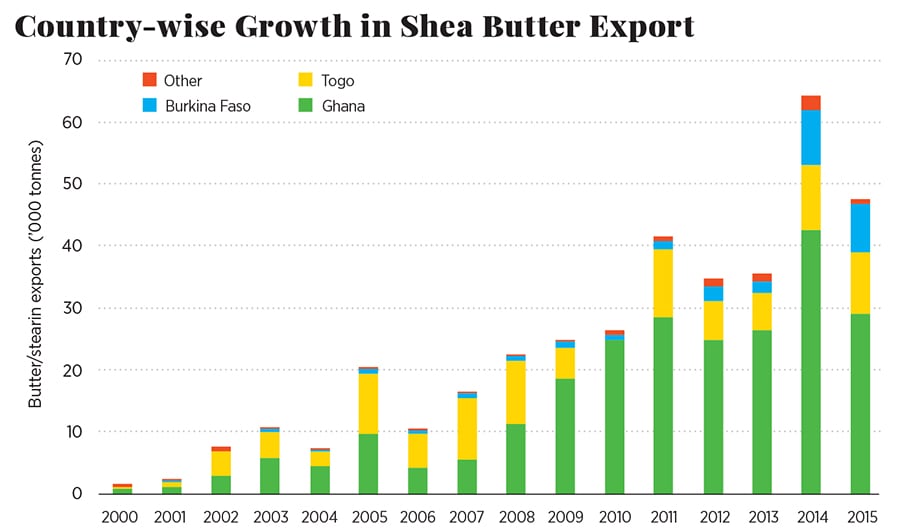

According to the Global Shea Alliance (GSA), in the last 20 years, the shea export market from African countries has grown by 600 percent, to 350,000 metric tonnes a year, creating approximately $200 million in annual income and employing more than 4 million women. While 90 percent of the shea produced in countries such as Nigeria, Ghana, Mali and Burkina Faso is consumed by the food industry (confectionaries, more specifically), the remaining is used by the cosmetics industry.

Conventionally, confectionaries that were categorised as chocolate used cocoa butter. However, a rising global demand for chocolates has meant that the price of cocoa butter has kept rising, pushing confectioners to look for cheaper substitutes. Cocoa butter equivalents (CBEs)—these include shea butter, palm and other vegetable oils—are estimated to cost 30 to 40 percent less than cocoa butter, according to CBI, the Centre for the Promotion of Imports from developing countries, which works with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands.

Shea butter is not only a cheaper alternative, but like cocoa butter melts at body temperature enabling confectioners to make chocolates of varying textures and consistencies. In 2000, the European Union allowed confectioners to use cocoa butter alternatives in chocolates, but restricted the use of these alternatives to a maximum of 5 percent of the chocolate product. Shea is one of the six alternatives currently allowed as an ingredient in these non-cocoa butter fats. The GSA says CBEs report a yearly growth of 10 percent (based on 2010 figures; the market has slowed down following the impact of the economic crisis).

*****

(Clockwise from left) The Mbanayili Health Centre; women in Mbanayili dance beneath kapok trees; shea kernels being crushed by a machine to make butter; the churning of shea paste to extract butter; women sort shea nuts to remove those of inferior quality

(Clockwise from left) The Mbanayili Health Centre; women in Mbanayili dance beneath kapok trees; shea kernels being crushed by a machine to make butter; the churning of shea paste to extract butter; women sort shea nuts to remove those of inferior qualityBut while the demand and market for shea butter grows, as does the income of the women who gather the shea nuts, there are clouds of concern gathering on the distant horizon. Climate change and forest degradation are affecting the production of shea butter in the same way in which they are affecting the farming of more controlled crops.

Winds from the Sahara are making the weather in Mbanayili increasingly hot and dry, thus reducing the yield. “The Sahara is expanding, with its surrounding regions becoming drier,” says Francesca Brkic, sustainable sourcing manager at The Body Shop, the British cosmetics and skincare company that procures its entire requirement of shea butter from Ghana, through the Tungteiya Women’s Association in northern Ghana. “A lower yield means women are picking up more kernels from the ground, leaving fewer seeds that can naturally germinate and grow into trees.”

The growing demand for shea butter in the food and cosmetics industries indicates its worth to these sectors, which are now increasingly becoming interested in sustainability efforts to ensure the availability of the product over the long term. Platforms such as GSA are now working with all stakeholders to not only promote the use of shea, but to also develop the quality of production and to ensure sustainability. GSA, which was formed in 2011, had started with two dozen partners and now has 450 partners, including shea collectors, suppliers, brands and retailers, and trade associates.

Brkic adds that efforts are being made under the United Nations’ Green Climate Fund to make investments in the conservation of shea trees and to diversify the livelihoods of women to supplement possible loss of income from shea collection and production.

According to the Green Climate Fund, Ghana’s landmass is fast losing its preponderance of forests, highly valuable savannah woodland species (including rosewood and shea trees) and wildlife due to destructive charcoal production, illegal logging, unsustainable farming practices, illegal mining, hunting, livestock grazing and human-induced fires. The Fund’s Shea Savanna Woodland Project is designed to promote sustainable approaches to land use, forest conservation, and enhanced community-based resource management to stem the ongoing degradation and deforestation.

Harvesting of shea kernels takes place once a year, between June and August. A sack of shea nuts (roughly 85 kg of nuts) yields between 25 kg and 30 kg of butter through the handcrafted process of extraction. Although The Body Shop procures only handcrafted shea butter, it is part of a small minority of procurers who do so. The vast majority of commercial buyers procure or use mechanical processes to extract butter.

Since the price of shea nuts is not controlled by the government, and is decided by market conditions, falling yields also mean that women who buy shea nuts from other women gatherers are paying a higher price per sack, while the rate at which they are selling to procurers remains the same.

“In the last year, our women have had to pay far higher prices for buying shea nuts [from other women who gather the nuts] because the yield has fallen,” says Fati Paul, chairperson of the Northern Ghana Community Action Fund (NOGCAF), the administrative body of the Tungteiya Women’s Association. “But the price at which we are selling the nuts to The Body Shop has remained the same. We will be renegotiating the price again this year.”

*****

The gathering and production of shea butter have traditionally been not just an economic activity for the rural women of Ghana, but also a social one. Going through the tedious process of breaking open the kernels, grinding them into a paste, and then extracting the butter is something that binds communities together. Gathering at a common place, after their day’s chores, gives the women an opportunity to share their stories, gossip and work together.

Hence, in Mbanayili, where members of the Tungteiya Women’s Association now have a mechanical crusher and grinder to process shea nuts, they still prefer to gather in the afternoons to manually extract butter from the kernel paste. They do this by vigorously stirring by hand large basins full of paste into which they gradually mix warm water; this helps liquefy the butter, which rises to the top. The butter is then skimmed off, and heated for about 30 minutes to get a clear oil; this is then sieved to remove particle impurities, and allowed to cool and harden into a solid, off-white lump.

“For women in Ghana, this lump is gold,” says Paul. “This has enabled them to have a voice in society.” The Association had started with 50 women members in 1994, and over the years has grown to 640, by providing women with a predictable annual income in a region where there are few other job prospects. “The association also works with about 11,000 shea nut pickers across the northern region, where Tungteiya sources its shea nuts from. These pickers supply nuts to the butter producers depending upon the season.”

The Body Shop’s association with the women of Mbanayili started in 1992, when Anita Roddick, the founder of the company, journeyed to Ghana while making a television programme on women entrepreneurs, and discovered shea. Two years later, in 1994, Roddick placed The Body Shop’s first order of shea through the Tungteiya Women’s Association.

Over the last 25 years, the company has increased the amount of shea it sources to 400 MT a year. It sources it from 11 villages around the town of Tamale in northern Ghana. In return, it supports about 49,000 people in the region through its community trade initiatives that provide clean drinking water, schools and health centres. The company does this by paying a premium (over and above the market price) for the shea nuts they procure.

“Change has come to Mbanayili, but it has been gradual,” says Pins Brown, head of ethical and sustainable sourcing at The Body Shop. “There is no revolution going on there. We are simply improving the situation.” Brown emphasises the need to respect traditional hierarchies and work within existing frameworks if improvements are to be made in any society.

The change in the lives of Mbanayili’s women—and, in turn, its children—has also been because of the control they now have over the shea nuts they gather or process. “Earlier, whatever shea they would gather in one season would have to be sold off, even at low market prices, because they had no space to store the nuts,” says Brkic. “If they stored it in their homes, and the homes were fumigated by the government to curb the spread of diseases like malaria, the nuts would get contaminated and would not be usable.”

Through NOGCAF, The Body Shop has built five warehouses in the villages from where it procures shea. The warehouses give the women the option to store the nuts, for up to five years, and the women can choose to make butter from them when market rates are better. “For The Body Shop, securing our production lines is directly related to securing the earnings of the local women,” says Brown.

As the incomes of Mbanayili’s women have become more secure, so have their positions within their families and societies. As the children gather around to watch and clap, the women sing and dance beneath the kapoks to celebrate the light that has already lit up their lives.

(The writer travelled to Ghana at the invitation of The Body Shop)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X